|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. From SFGATE, Written By Andrew Chamings.

A remarkable scientific discovery published this week based on the DNA of eight living members of the Ohlone Tribe could result in federal recognition for the first residents of the Bay Area.

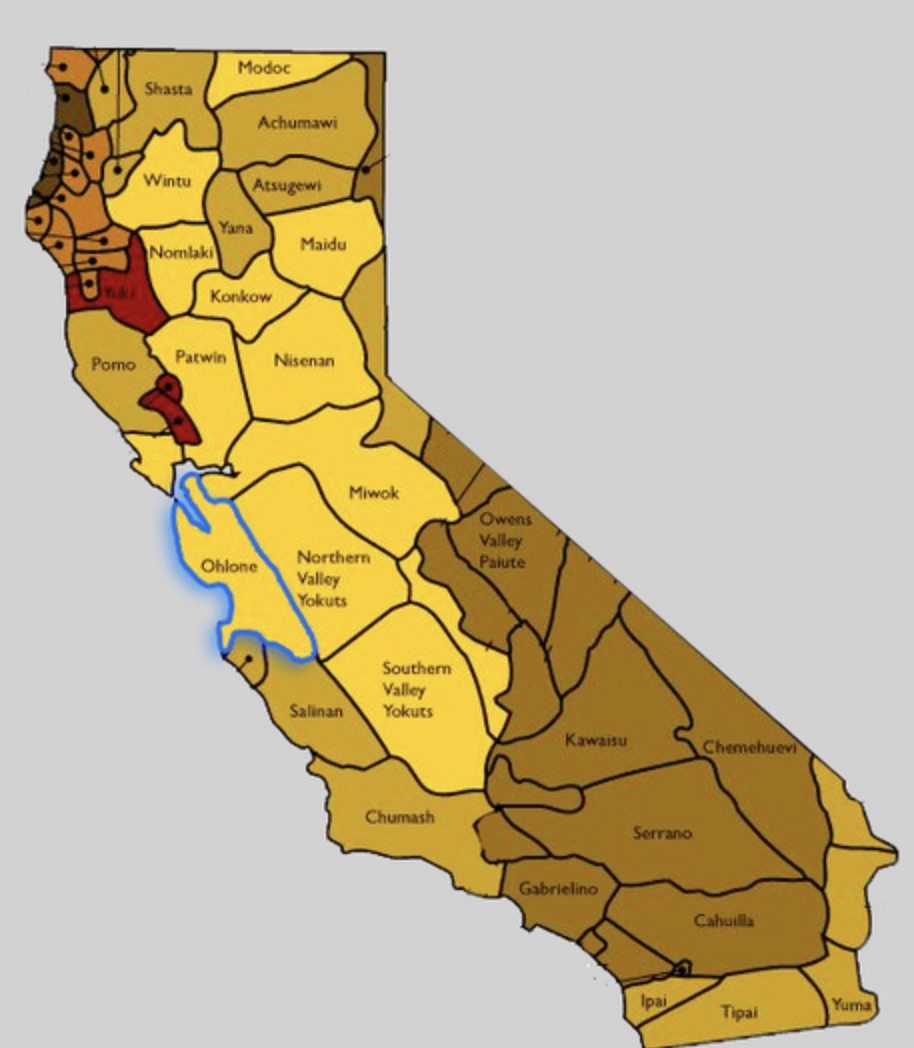

Before the Spanish colonized California about 250 years ago, it’s thought that up to 30,000 Indigenous Ohlone lived across the land. By the 1920s, there were fewer than 100 remaining. In 1925, a UC Berkeley anthropologist wrote that the Ohlone were “extinct for all practical purposes.”

The genocidal history of the Spanish, and later European, colonization of what is now California is still being reckoned with today. In Gilroy, a feud is currently playing out on the installation of a “Mission Bell” in the town center, a commemorative item some see as a representation of “the destruction and domination of Native American people.” Starting in 1769, the Spanish built a string of 21 missions throughout California, largely through the forced labor of Indigenous people.

But an unlikely DNA link, reported in a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on March 21, may lead to a big step toward legitimacy and recognition for the Ohlone people.

The tribe currently has about 500 members living in California. Since the 1980s, the tribe has been fighting to prove their historic presence in the Bay Area through genealogy and analysis of death and marriage records from three Bay Area missions.

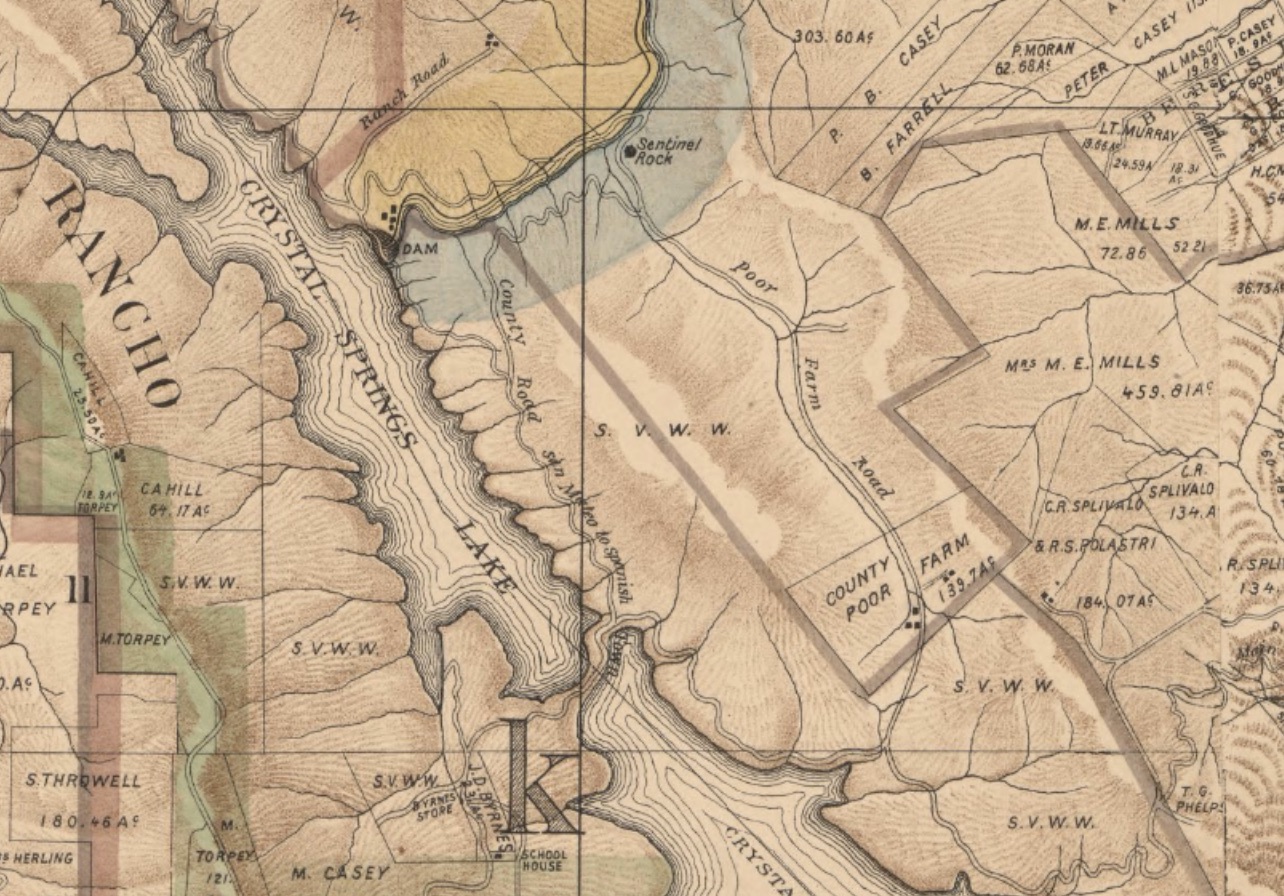

Six years ago, archaeologists at a construction site in Fremont found two ancient Indigenous villages. One was thought to be occupied as far back as 490 B.C.E., the other founded around 1345 C.E. DNA there, taken from the skeletal remains of 12 individuals, identified the Ohlone’s genetic signature, and the new study has linked that DNA to eight living members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. According to the tribe, the present-day Muwekma Ohlone is composed of all of the known surviving lineages “aboriginal to the San Francisco Bay Area region.”

The finding corroborates the tribe’s long-fought claim for legitimacy and contradicts the idea that the Ohlone migrated to the area between 500 C.E. and 1,000 C.E., a notion based on artifact and language patterns.

“We analyzed a large number of ancestral remains for DNA preservation and focused on those with the best DNA preservation for this study,” Ripan Malhi, a professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, who led the research with Stanford University, said in a statement from the college. “We also worked with the Ohlone to sample saliva from present-day community members so we could compare the DNA from both groups.”

It’s hoped the findings will finally result in federal recognition for the Muwekma Ohlone. The tribe now plans on working with politicians to give them legal sovereignty and access to programs established on a federal level to support Indigenous tribes.

“By creating these collaborations and having them published with Muwekma co-authors, it’s not just hearsay or self-identification, it’s meaningful science,” co-author of the study Alan Leventhal told Science.org.

More on Coastside Ohlone History on Coastside Buzz

More on Coastside History on Coastside Buzz