|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

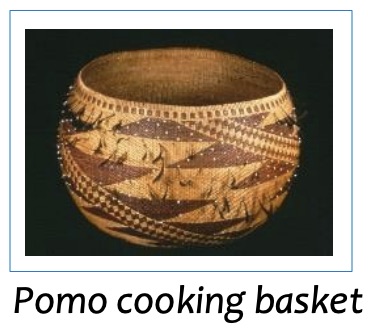

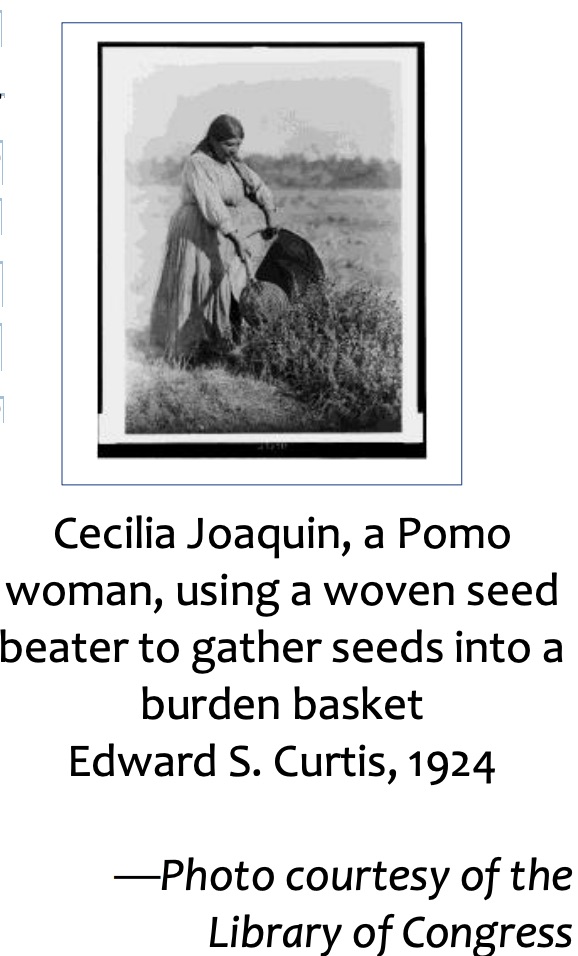

HISTORY. The woman looked out to the ocean, letting her eyes rest awhile. She had been working for a long time on the very small, intricate weaving of the plants beneath her hands. It took such time and care to make sure that once filled with water, her new cooking basket would not leak. She had worked all morning in the meadows around the village, harvesting wildflower seeds like Clarkias in a seed basket. The seeds would be roasted on a roasting basket tray by rolling a hot coal around in them, and then made into a nourishing paste added to meals.

As she focused on the beach below the bluff tops, she could see the men and boys throwing out the large fishing nets, made and repaired by the people using cordage in an easy technique to twist plant fibers like hemp into ropes. She could also see the duck hunters in the nearby lagoon, hiding behind tule reeds as they watched the birds begin to swim into their basket traps, several of which she had helped to make.

As she focused on the beach below the bluff tops, she could see the men and boys throwing out the large fishing nets, made and repaired by the people using cordage in an easy technique to twist plant fibers like hemp into ropes. She could also see the duck hunters in the nearby lagoon, hiding behind tule reeds as they watched the birds begin to swim into their basket traps, several of which she had helped to make.

Her eyes returned to look at the ocean, and slowly they lost focus as she rested and sought inspiration for the continued pattern of her basket. The designs she made with different colored plant fibers represented her clan lines and certain landmarks, but she also had choices about representing her own feelings. Like many artists, she looked all around her for signs, for a vision to come to her.

She had so many other decisions to think about. Should she spend more time in the meadows before her people packed up and left the oceanside for the foothills? She needed to make sure that all the seeds were harvested, and the meadow ready for its burn. She also wanted time to dig along the creekside for white sedge roots, an important plant for her baskets.

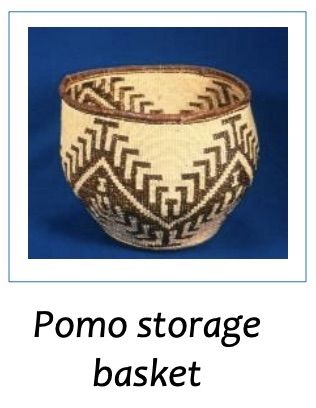

But she also needed to finish the cooking basket and start another one, for acorn storage. Those baskets would be used in the oak woods in the Fall, and they had to be as tight as possible to keep out insects and yet let air in to keep out mold.

For her cooking basket she had made a choice: redwood burl shoots gathered in the Spring. Once woven and then wet, the fibers would expand to create such a tight weave that the basket could hold water. And she made another choice: she cut a thin coastal willow branch, and curved it to form a full circle. She would tie the cut ends together side by side, forming a handle. The curved end could now carry a heated, round stone to be dropped into a cooking basket full of water. In no time, the water would boil, but the stone had to be stirred constantly to keep it from burning through the basket. Acorn meal, berries, nuts, meat or fish, bulbs…all could be added to the water to make a stew.

For her cooking basket she had made a choice: redwood burl shoots gathered in the Spring. Once woven and then wet, the fibers would expand to create such a tight weave that the basket could hold water. And she made another choice: she cut a thin coastal willow branch, and curved it to form a full circle. She would tie the cut ends together side by side, forming a handle. The curved end could now carry a heated, round stone to be dropped into a cooking basket full of water. In no time, the water would boil, but the stone had to be stirred constantly to keep it from burning through the basket. Acorn meal, berries, nuts, meat or fish, bulbs…all could be added to the water to make a stew.

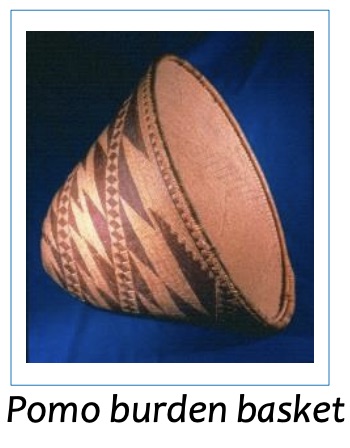

She also needed to help her youngest daughter with her small burden basket, as she was still learning to weave and her small fingers could not manage the more tightly woven baskets. It was also important for her daughter to understand about choices, that there were always more tasks to do than time to do them. Deciding what to do and when were important lessons for her children, as they would all be expected to participate in the village and family activities, yet finish what was theirs to do.

As a weaver, her daughter would have to find her own vision, her dream-world messages that would be channeled into her choice of designs and the plants to use. Above all, her daughter was learning that all living things were equal to one another, including plants. As she worked gardening all the plants essential to their food and fiber needs, she would become skilled at weeding, pruning, coppicing for new shoots, and learning when to harvest each one.

And her daughter would participate in the most important gardening activity of all, with her whole village: the highly controlled, low-intensity seasonal burns that made so many plants stronger, bear more seeds, and provide new growth attractive to deer and other prey. Burns around the village would also take away shrubs that could hide bears, particularly the great predatory Grizzly Bears that her people feared the most.

would participate in the most important gardening activity of all, with her whole village: the highly controlled, low-intensity seasonal burns that made so many plants stronger, bear more seeds, and provide new growth attractive to deer and other prey. Burns around the village would also take away shrubs that could hide bears, particularly the great predatory Grizzly Bears that her people feared the most.

The woman also thought about another decision she had to make: the exact design and shape she should use for the gift basket that she would next make for the meeting with a neighboring village headman. She had a choice from among the many shells and bird feathers she could weave into the ceremonial basket that the recipient would accept. She had been chosen to make that basket because her healing baskets had been known to help people who were ill.

Weeks later, as the woman and her people left the ocean bluff top village for the next seasonal site in the foothills, they burned the tule reed homes. This removed all insect and rodent infestation; and as they migrated around to 3 or 4 sites in a normal year, they would construct new homes each time. And the woman and her people would again garden all around them, and she would make new choices in her craft that was so essential to their way of life.

~ All photos courtesy of California State Parks

~ Written by Mary Ruddy

More About Ohlone Basketry

California’s native peoples have long been considered the most skilled of all basket creators. Their diverse functionality and beauty made those baskets desirable to 19th -century Russian traders along the Mendocino and Marin coastlines. To this day, the best of all California Native American baskets, including Ohlone ones, are in Russian museums.

In California after European contact, colonization, disease, loss of plant habitat, and loss of Ohlone territory and autonomy meant that the baskets of peoples like the Ohlone were lost, their art and function no longer valued by those in power. Today the closest we can come to admiring the lost Ohlone baskets is to see the baskets of their nearest neighbors, the Pomo from beyond the northernmost Spanish missions.

Those few Ohlone baskets that survived into the 20th century were carefully stored in museum cases or basements, the antithesis of how the people who made and used them saw their place of honor in their culture. Mabel McKay, a most famous basket weaver and spiritual healer among her Pomo people, was once asked how best to care for those museum baskets. Her answer was to take them out of the cases, hold them and talk to them… because they were alive and needed to thrive.

Families would have had two dozen or more baskets that would be moved with them in the seasonal migrations. Among the many kinds there were seed beater baskets, basket traps for fish, fowl, and small mammals, storage baskets, burden-carrying baskets, seed-roasting baskets, cooking baskets, and baby cradles.

The plants used were, for example: sedges, redbud bark, dogbane, ferns, nettles, bear grass, bunch grasses, milkweed, iris fibers, hemp, tule reeds, hazelnut branches, willow bark, and even poison oak.

Typically, one weaver would need 10,000 shoots in a year of weaving, all harvested after careful long-term planning and gardening in an area of only 3 square miles!

The work done before the first knots were tied could represent up to 3 years of gardening by the whole village.

Baskets were used in all facets of life: food collection, preparation, storage, hunting, fishing, traveling, and clothing, and were held in esteem as status symbols as well as used in medicinal and religious rituals. They were also made as gifts and peace offerings, and each was an artistic and wholly integrated part of its weaver.

~ Written by Mary Ruddy

Suggested Reading

Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources by M. Kat Anderson. University of California Press, 2005.

California Indians and their Environment by Kent Lightfoot and Otis Parrish. University of California Press, 2009.

Mabel McKay: Weaving the Dream by Greg Sarris. University of California Press, 1994.

Mary, What a fabulous creation of a story based on your extensive knowledge of the Ohlone culture. You really brought this woman to life. I could picture her and her daughter and all the scenes you described. Magical and informative.