|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. Authored by Andy Howse from the Open the SF Watershed website

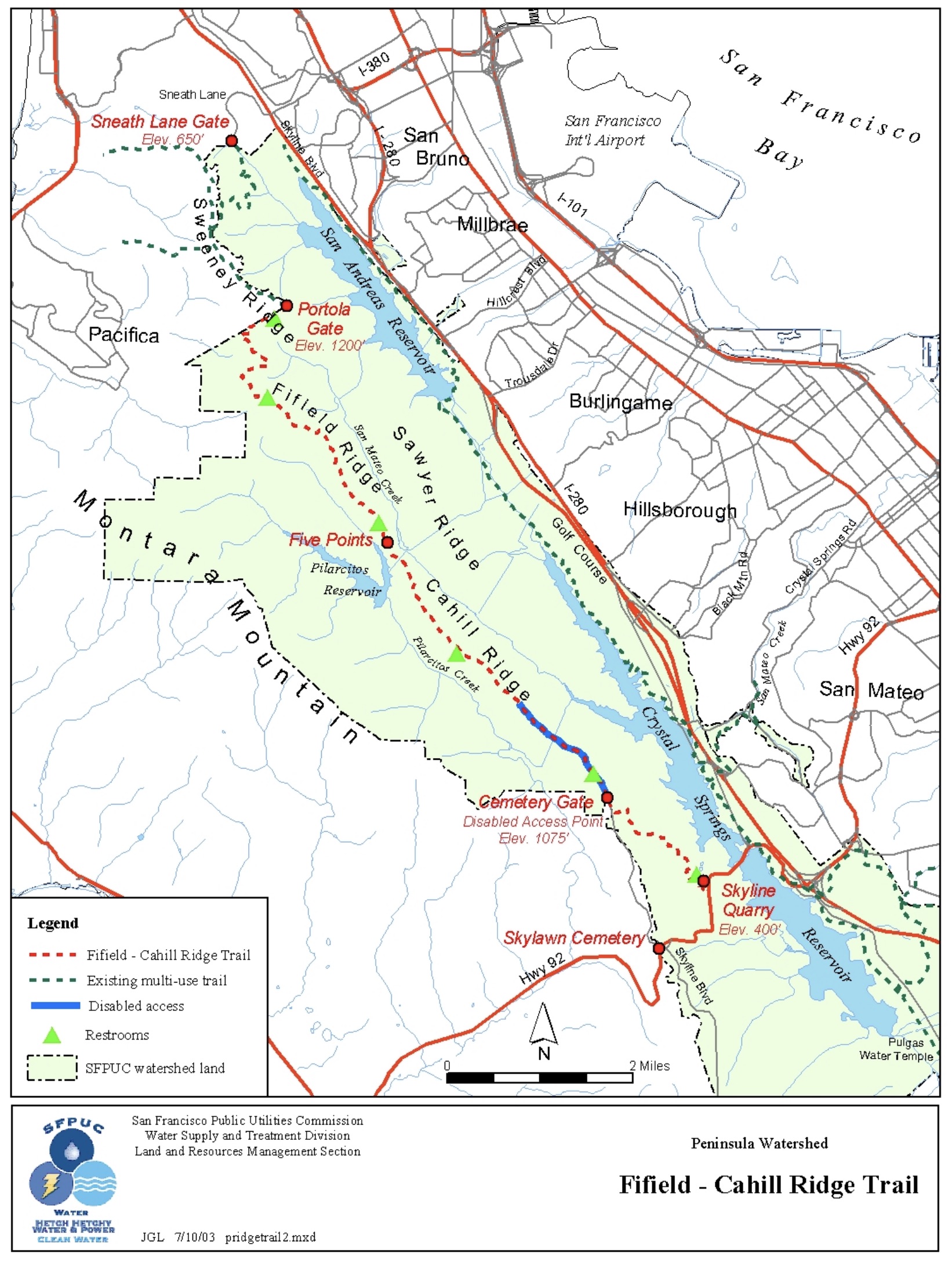

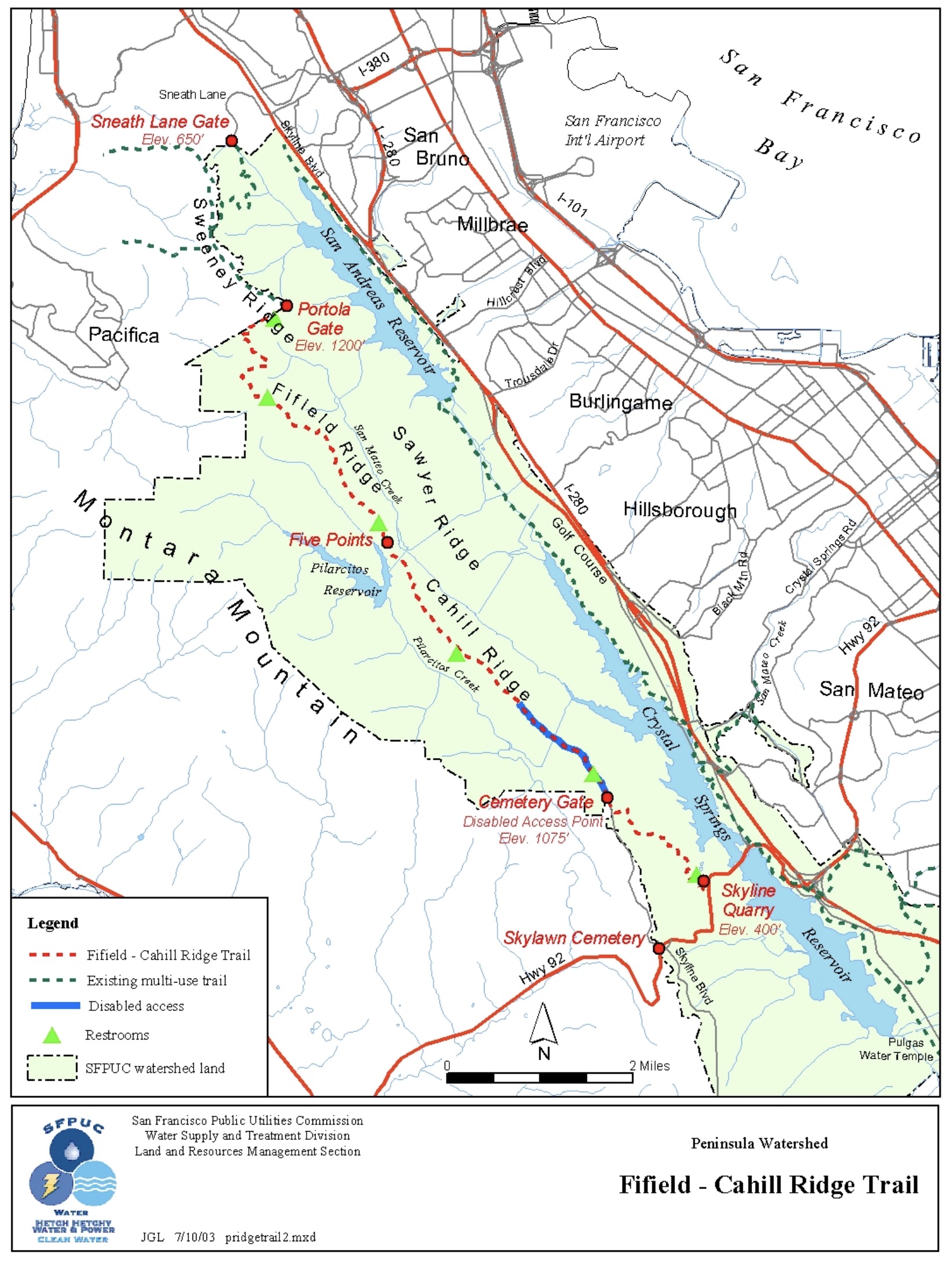

OpenTheWatershed.org is a local environmental and outdoor organization that has been working with the San Francisco Public Utility Commission to improve public access to its 23,000 acre Crystal Springs Watershed in San Mateo County. While we recognize that the SFPUC’s primary mission is to provide drinking water to San Francisco and beyond, we believe that this mission is fully compatible with improved public access to the area. OpenTheWatershed.org strongly supports the public access improvements now planned by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission but would like to see a more far-reaching plan pursued.

SFPUC Assistant General Manager Steve Ritchie summarized the SFPUC’s plans for near and medium-term public access improvements in a December 2014 letter summarized at a San Francisco Board of Supervisors hearing April 2014. Mr. Ritchie and Tim Ramirez, the SFPUC’s Watershed Manager, presented these plans. A large majority of the several dozen speakers at the hearing were strongly in favor of the plans and our outreach efforts have consistently found the public is excited to visit the Watershed. Our organization’s primary goal is to improve public access to the Watershed, but we are also an environmental organization, and we applaud the SFPUC for its careful studies, adherence to environmental regulations and its ultimate decision to move forward with these projects.

We understand that some groups, such as the Committee for Green Foothills, would prefer the Watershed remain closed to the public, but we believe that the currently planned improvements, improvements encouraged by the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and other trail openings will not harm the area’s delicate environment or the viability of our water supply for the following reasons:

• Minimal Impact – Most of the planned improvements do not require new trails or any construction but will simply open existing service roads to the public. Where trail construction is required, it can be done in an environmentally responsible way, as is standard practice in the Bay Area’s other Watersheds and open space areas.

• Water Security – New routes planned for public access are no closer to the reservoirs than existing, publicly accessible routes. While wildfires and illegal activity in the Watershed are minor concerns, the proposed new permit system will ensure that visitors know and agree to abide by the SFPUC’s rules. Responsible visitors will act as “eyes on the trail” to help deter illegal activities.

• Water system improvements – The Crystal Springs Watershed is largely a back up system to the Hetch Hetchy Water supply. The $283 million upgrade to the Harry Tracy Water Treatment Plant above Millbrae will greatly increase the reliability of this backup. Simultaneously, the seismic upgrades to the Hetch Hetchy system will greatly decrease the need for Crystal Springs to act as an emergency supply. Combined, these construction projects will more than compensate for any hypothesized additional risk to the system caused by increased public access. As we look forward to the planned 2019 completion of the projects currently underway, we urge the SFPUC to take concrete steps to open the Whiting Ridge Trail and plan out additional environmentally sustainable openings for routes to the coast and easily accessed loop routes.

•The benefits are compelling: Regional trail connections – These projects would link the Watershed to surrounding local, state, and GGNRA parkland and establish a truly interconnected trail system a system remarkably similar to, yet larger than that operated with the cooperation of the Marin Municipal Water District. This would be a tremendous resource for residents of northern San Mateo County and southern San Francisco.

•Public Health and Happiness – Both of these areas, many of whose residents are low-income, are currently underserved by open space. Access improvements could significantly improve the health, happiness, and quality of life.

•Achievability – Rarely is there an opportunity to do so much good with so little investment: As noted above, the trails we seek to open are, for the most part, existing dirt service roads, already routinely used by maintenance trucks. Little new construction would be required, meaning that both cost and the potential environmental impact would be minimized.

We urge all parties involved to come together and plan for comprehensively improved public access to the Watershed. The opportunities to connect with nature, exercise, and enjoy the great outdoors will be greatly appreciated by current and future generations of San Francisco and San Mateo County residents.

THE HISTORIC SF PENINSULA “CRYSTAL SPRINGS” WATERSHED

From the Southern end of Sweeny Ridge in San Bruno to the eastern end of McNee Ranch in Pacifica, is an open space area that stretches all the way to highway 92 and then south past Filoli. This 23,000 acres property is not wilderness, it has in it an entire network of well-maintained service roads, some of which have a history of use all the way back to the 1860’s. The dirt and gravel roads in the area wind their way through thick forests of redwood, cypress and oak trees. The roads go past a beautiful mountain lake, Lake Pilarcitos, which was the first reliable water source for the city of San Francisco.

This is the SF Watershed, and you are forbidden to go there. The SF Watershed land is managed by the SFPUC, otherwise known as the San Francisco Water Department. It is entirely closed to the public; it is only open to a few select SF water department employees and a few politicians from San Francisco. The SF Watershed has some of the most important historical sites in the Bay Area, and because it has been closed for so long much of this history is forgotten from public consciousness.

The untold history inside the watershed is as important as the Bay Area discovery site, Mission Dolores, the Barbary Coast Trail, or any of our historically important places. Pilarcitos Dam was completed in 1867 right after the civil war. Designed by master engineer Herman Schussler it was a marvel of engineering for its time. The dam created the first reliable water source for San Francisco, Pilarcitos Lake. Water was shipped to the city via a redwood flume powered by gravity. Before this development water in San Francisco was sold by the barrel. Without water the city would not have grown, when you consider how much the San Francisco Bay Area has shaped the history of the world, it puts into perspective how important this dam is to our cultural history. There is at the plaque at Pilarcitos Dam placed in 1967 at the one hundred year anniversary of the construction of the dam. It is a plaque paid for with public money, on public land, that no one in the public is allowed to see.

There are other significant historical sites in the watershed, including Stone Dam, pieces of the redwood flume that are still standing, homes dating back to the 1860’s and countless other artifacts left un accounted for left by the Spring Valley Water company before it was acquired by the San Francisco Water Department in the 1930’s.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

In the San Francisco Peninsula Watershed, Public Access and Environmental Protection are Compatible Priorities

As the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission prepares to implement its plans to improve public access to the Peninsula Watershed in 2016 and beyond, protection of the delicate environment of the area is, and should be, a top priority. Environmental protection and sustainability are also top priorities for OSFW as well. We are happy to present answers here to some of the most frequently asked questions about environmental protection in the Watershed:

Are the PUC’s plans putting public access ahead to the Watershed ahead of protecting the area’s environment?

The two short answers are ‘no’ and ‘They couldn’t even if they wanted to.’ Protecting the delicate environment of the Peninsula Watershed is one of the PUC’s top priorities. The PUC owns and operates the Watershed, but it does so under the supervision of local, state, and federal environmental regulatory agencies, all of which must approve any plans or projects before they can begin. The PUC is moving ahead with its plans to improve public access only because it—and the regulatory agencies—are completely satisfied that these plans will not harm or risk harm to the Watershed’s environment.

How does the PUC know that improved public access will not harm the Watershed’s environment?

The PUC’s 376-page Watershed Management Plan, the product of years of work by in-house and outside experts, analyzed a vast array of potential environmental issues, including but not limited to water runoff, erosion, air quality, fires, noise, endangered species habitat, invasive plant and animal species, and hazardous materials entering or leaving the Watershed. The Watershed Management Plan found that on every single dimension, risks from the limited and carefully controlled public access the PUC is planning were either insignificant or could be mitigated by the policies themselves, for example by banning dogs to reduce risks to endangered species. The PUC’s plans are, by law, overseen by all relevant environmental agencies to ensure that nothing was missed. The Watershed Management Plan is publicly available at this link.

How will the PUC ensure that visitors obey the rules and behave responsibly?

The PUC is still in the process of drafting the rules for visitors to the Watershed, based on the findings in its environmental studies. These rules will be the basis of an online mini-course, complete with quizzes, that people wanting to visit will have to complete before receiving a permit to visit the Watershed. The PUC will continue to patrol the Watershed carefully for any unauthorized use or anyone without a permit.

What about the risk of illegal uses of the Watershed, like marijuana farming?

The Management Plan found that some of the greatest risks to the Watershed’s environment come from unauthorized uses. This, however, is not a reason to prohibit authorized access, just as the risk that a burglar might break into your home is not a reason not to invite your friends for dinner. Criminals intent on entering the Watershed for illegal purposes, such as growing marijuana, would much prefer that there be fewer, rather than more, authorized people in the area: just as urban criminals prefer deserted streets. The experience of other Bay Area agencies, including the Marin Municipal Water District, which has for a century overseen open access to its watershed, and the East Bay Municipal Utility District, which uses a permit system similar to the one planned for the Peninsula Watershed, is that authorized users—“eyes on the trails”—are a major deterrent to criminals, and authorized users can find and report illegal activity.

How does public access to the Watershed connect to other environmental goals?

Improving public access to the Watershed is part of a broad, long-term strategy of making the Bay Area environmentally sustainable. A major problem with the current system of docent-only access to the Watershed is that it makes it nearly impossible to visit the Watershed without using a car. The permit system, by allowing visitors to come on their own schedules, will allow them to arrive there by public transit, on foot, or by bike.

Shouldn’t some special places simply be off-limits to humans?

While this is in some ways a philosophical question, in United States law and practice, the answer is ‘no.’ Even land federally designated as Wilderness, the most stringent level of protection available under American law, does not exclude public access. The National Park system, our nation’s system of treasuring and preserving our most important places, is based explicitly on the idea that responsible public access and protection for the environment are mutually reinforcing priorities.

Moreover, the Watershed is many things, but it is not untouched nature. People have played a role in the Watershed throughout California’s history. Native Americans lived in the area, and one of the earliest stagecoach routes across the Peninsula ran right through it, complete with an inn and restaurant run by Leander Sawyer. The reservoirs and water pumping systems, now the defining feature of the area, are a human intervention on a vast scale, part of a vital piece of public infrastructure stretching from Yosemite to San Francisco. The roads through the Watershed, many of which are paved, are used daily by the PUC’s trucks. The question is thus not whether there will be human activity in the Watershed but on what terms.

The purpose of the environmental review process—California’s is by far the nation’s strictest—is precisely to determine what activities, like public access, are compatible with protecting the environment of delicate areas, and the plans currently moving forward for improved public access are the result of a long and careful process. We look forward to enjoying the planned improvements to public access in the Watershed, and when we do, we’ll know that our visits are not a threat to the area.

Did You Know There is a Road From El Granada Blvd. to Milbrae?

ARTICLE. Authored by Andy Howse from the Open the SF Watershed website

The Road to El Granada. Hmmmm.

As the crow flies, Millbrae, California, which sits on the bay side of the northern San Francisco Peninsula, is roughly eight miles from the town of El Granada, which sits on the Pacific. To drive from Millbrae to El Granada, however, depending on which route you choose, and how much you like to meander, will take you between twenty and twenty five miles, but that was not always the case. When the first roads on the Peninsula were built, most of which are still in use, there was a road that made a near beeline from Millbrae due southwest to El Granada. It still exists today.

The landscape that surrounds this road has changed a lot since the 1860s. The stories of how and why it changed tell a narrative that brought the region of Northern California from the place where the Old West met the sea to what we know as the modern world. There are more stories than we can go over here, but if recounted correctly, they tell a tale of the landscape surrounding this road that revolves around the two life-bloods of any society: money and water.

At 280 and Larkspur Drive, near the we stern end of Millbrae Avenue, is an entrance to the most popular park in San Mateo County, the Sawyer Camp Trail. A short walk on this trail will take you to a beautiful, interesting, and historically important place, the San Andreas Dam. Built in 1868, it dammed the creek that ran north-south down the resort town of Crystal Springs, and acted as a bridge across the valley for travelers heading west across to El Granada. The scenery here is serene, yet the dam’s harnessed power of both humans and nature balances squarely on the San Andreas Fault. A feat of engineering for its time, the earthen dam proudly withstood the 1906 Earthquake with only slight damage.

stern end of Millbrae Avenue, is an entrance to the most popular park in San Mateo County, the Sawyer Camp Trail. A short walk on this trail will take you to a beautiful, interesting, and historically important place, the San Andreas Dam. Built in 1868, it dammed the creek that ran north-south down the resort town of Crystal Springs, and acted as a bridge across the valley for travelers heading west across to El Granada. The scenery here is serene, yet the dam’s harnessed power of both humans and nature balances squarely on the San Andreas Fault. A feat of engineering for its time, the earthen dam proudly withstood the 1906 Earthquake with only slight damage.

Just up the road from the dam, near the top of the ridge, lay the dairy farm of W.J. Fifield. Fifield and his brother had been operating the dairy farm as far back as the mid-1860s. As the dairy was situated on the road to the coast, it had to routinely send workers into the town of Millbrae for supplies and business affairs. Such was the case the evening of Tuesday, June 22, 1886, when an employee of Fifield’s, a Mr. Joseph Sine, was driving a horse-drawn wagon back to the Dairy Farm. Unbeknownst to Sine, his companion on the wagon, a man named Peter Coetaneno, had plans to ambush him. At the dam, Coetaneno asked Sine  to let him off the wagon, preparing to do something that would eventually make him a wanted man. The next day, the Daily Alta, a newspaper out of San Francisco, reported that W.O. Booth, a lawman out of San Mateo, had issued a warrant for Coetaneno, it reads:

to let him off the wagon, preparing to do something that would eventually make him a wanted man. The next day, the Daily Alta, a newspaper out of San Francisco, reported that W.O. Booth, a lawman out of San Mateo, had issued a warrant for Coetaneno, it reads:

…”calling for the arrest of a Greek named Peter Coetaneno, who is wanted on a charge of murder. The wanted man is about thirty years of age, looks like a Spaniard, weighs about 145 pounds and stands about 5 feet 7 inches high. His hair and moustache are jet black, and on his nose is a peculiar scar. When last seen he wore a black suit of clothes and soft felt hat. Coetaneno left Pilarcitos Lake about midnight, June 21st, and presumably started for San Francisco.”

When Peter Coetaneno stepped off the wagon, he turned and shot Joseph Sine twice in the chest. The next day’s Sacramento Daily Union described the wounds in detail:

…”one (bullet) took effect in the breast, striking the rib, passed around the body and lodged in the muscle of the back. The wound is not necessarily fatal. The officers of San Mateo County are scouring the hills for the would-be murderer. Mr. Fifield says it was a preconcerted plan to kill Sine; that Castino had been waiting two hours on the road before he got on the wagon.”

Sine must have lived long enough to tell his story, though it’s not clear if he survived: the Daily Union reported “Sine as doing well, and will likely recover” and the Daily Alta reported the story as murder. Notably the Alta and the Union spelled the assailant’s surname differently, and neither newspaper (to my knowledge) ever reported Coetaneno’s (or Castino’s) capture. As for Fifield’s Dairy Farm, the excrement from the cows, among other things, was enough of a nuisance that in March of 1902, the Spring Valley Water Company took him to court. Later the  Water Company purchased his 1,107 acre farm altogether.

Water Company purchased his 1,107 acre farm altogether.

By the 1890s, the Spring Valley Water Works was a monopoly in San Francisco, but it was the 1860s when it initiated its enterprise in Pilarcitos Valley, west of Fifield’s Dairy. When Spring Valley’s first engineer, Colonel A.W. Von Schmidt, oversaw the creation of Pilarcitos Lake Reservoir in December of 1863, it was such a success that the dam was raised in 1867 to keep up with demand. The waters of Pilarcitos Lake were brought to Laguna Honda in San Francisco via a redwood flume, and allowed the thirsty city to grow at a time when potable water was being sold by the barrel, for gold.

Over time, Pilarcitos Lake became a destination location for San Francisco’s well-to-do and residents of the Peninsula for daytrips, picnicking and fishing. A lakeside cabin was built to host visitors, and water quality was analyzed and praised for its ability to be use in brewing beer. Muskellunge Pike were brought in from the mid-west for the enjoyment of anglers. Fortunately for any native species, the invasive predatory fish never took hold as the Daily Call newspaper reported in 1893. There was serious talk of building an electric trolley line to L ake Pilarcitos in 1912. The lake was advertised as a destination spot in San Mateo County by the San Mateo Chamber of Commerce as late as 1930.

ake Pilarcitos in 1912. The lake was advertised as a destination spot in San Mateo County by the San Mateo Chamber of Commerce as late as 1930.

In the time period between 1910 and 1926, the Spring Valley Water Company was openly advertising to the public the glory of the locales owned by Spring Valley. Willam Bours Bourn II and Willam Ralston, the company’s largest stockholders, stood to make a lot of money if their stock in Spring Valley was purchased by the city of San Francisco. In 1910, Bourn commissioned his friend Willis Polk to design a water temple, based on the Temple of Vesta in Italy, at the east end of Niles Canyon in Sunol. In an attempt to appeal to SF voters, Spring Valley’s own magazine SF Water described the beauty, recreational activities and history of the lakes at Pilarcitos, Stone Dam, San Andreas and Crystal Springs. In the July 1926 SF Water magazine, an author identified only as “Contributed” described Lake Pilarcitos in one of the most beautiful run-on sentences of all time:

“Here is the most beautiful portion of California, unspoiled by man, a park of Nature’s own making, where beings animate and inanimate reach the perfection for which they were intended; a land of fountains, streams and waterfalls and lakes, of fern and fruit and flowers, of trees and thickets, of sunlight and shadow, of peace and plenty.”

Fountains were built at Lake Pilarcitos and at the Sunol Water Temple across the bay, created to quench the thirst of the visiting public that Bourn and Ralston were so eagerly courting. These opulent fountains still exist today. Like so many other relics of the Spring Valley Water Company and the era at large, they were designed to appear as though from antiquity. They are four-sided, and each side has what appears to be a rather menacing face. In a time still connected to the settling and taming of the west and the grandiose ethos of Manifest Destiny that drove it, these ornate relics embody the Spring Valley’s own subtle ethos that building great infrastructure for civilization somehow connected them to the great civilizations of the past. Through email, I was able to make contact with UC Berkeley professor and author of “Imperial San Francisco” Dr. Gray Brechen. The Professor surmised:

“The fountains and their faces were probably designed by Willis Polk who was William Bowers Bourn’s court architect. He designed the Sunol Temple as well as other facilities for the Spring Valley Water Company including its headquarters on Mason Street. There you will see terra cotta that mimics water running down the front of the building the way that you see under the faces…”

… “The faces themselves seem to be taken from classical depictions of Neptune and river gods: old men whose beards are running water. Although Polk was not trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he was so good that he may as well have been, and he probably hired others who were since he had one of the leading architectural offices in SF.”

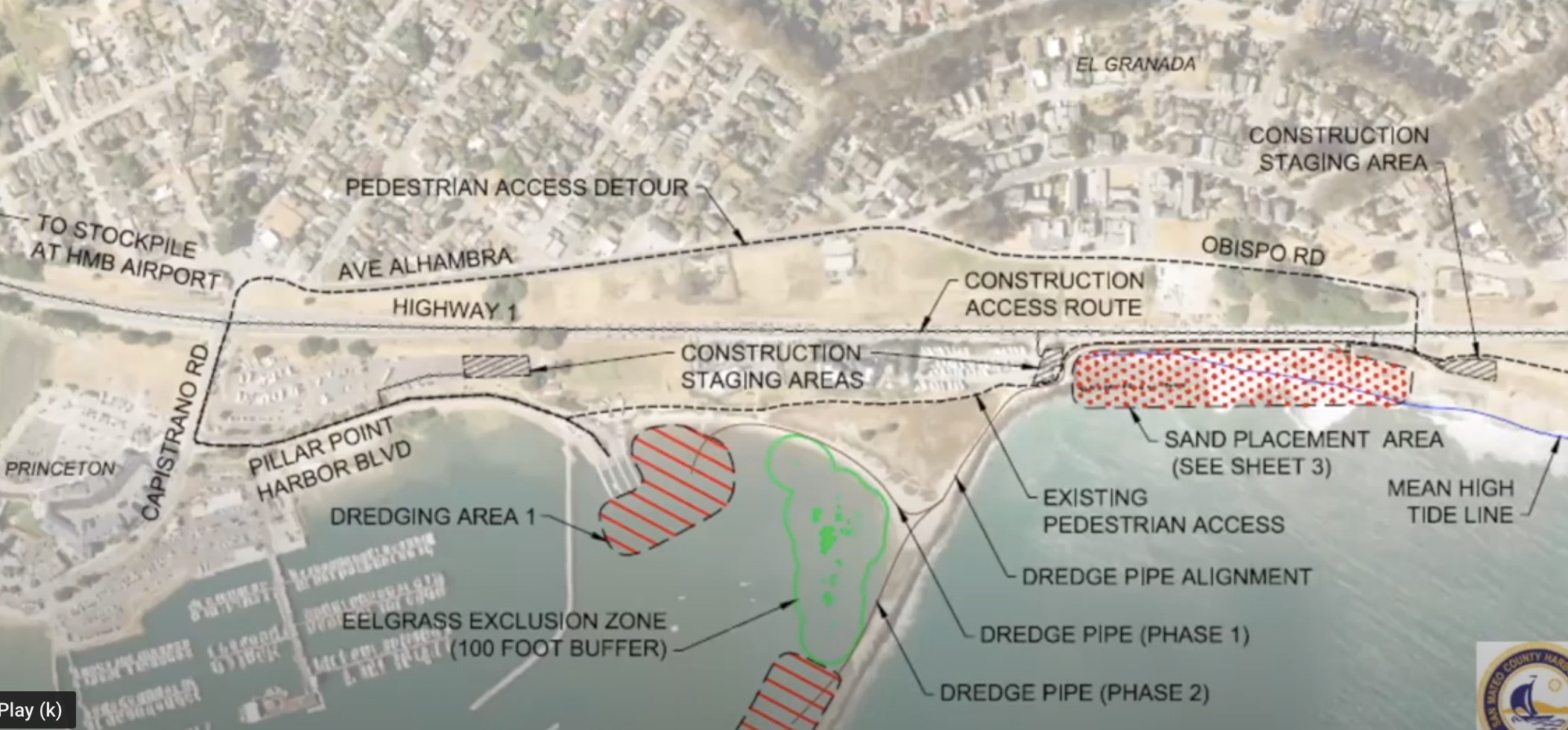

Surrounding Lake Pilarcitos remains an entire network of roads that traverse both north-south and east-west. The roads run along both ridge lines of Pilarcitos Valley and along Pilarcitos Creek. One road followed Pilarcitos Creek to the Pacific in Half Moon Bay, known in the 1860s as “Spanish Town”. The road to El Granada from Lake Pilarcitos heads westward, up the hill and down through what is now the GGNRA National Park of Rancho Corral De Tierra, through private property, and eventually turns into El Granada Boulevard, a public road well-known by residents of the Coastside SF Peninsula.

Today, El Granada is as scenic and beautiful as ever. It hosts surf competitions and festivals; it has hotels and a brewery. El Granada and the surrounding coastal towns have always been beautiful places and today they are a destination for tourists. On the wrong weekend, they may seem crowded, but most of the time El Granada may be described as sleepy. (This is especially true when compared to the scene in Millbrae, where the cars on 101 roar and jetliners scream into and out of SFO.) In that way it is still somewhat similar to the 1860s, when the tourists could travel the road a mere eight miles from the El Camino on the busier bay side for a day at the coast.

The rest of the story >>

The Raker Act of Crystal Springs and more!

Andy Howse spent several year researching the history of the Crystal Springs Watershed. The result is a 10-part essay/podcast that is one hell of a story, right in our own backyard.

Want to Go on a Watershed Hike or Bike Ride?

It is FREE!