|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. Authored by Andy Howse from the Open the SF Watershed website

The Road to El Granada. Hmmmm.

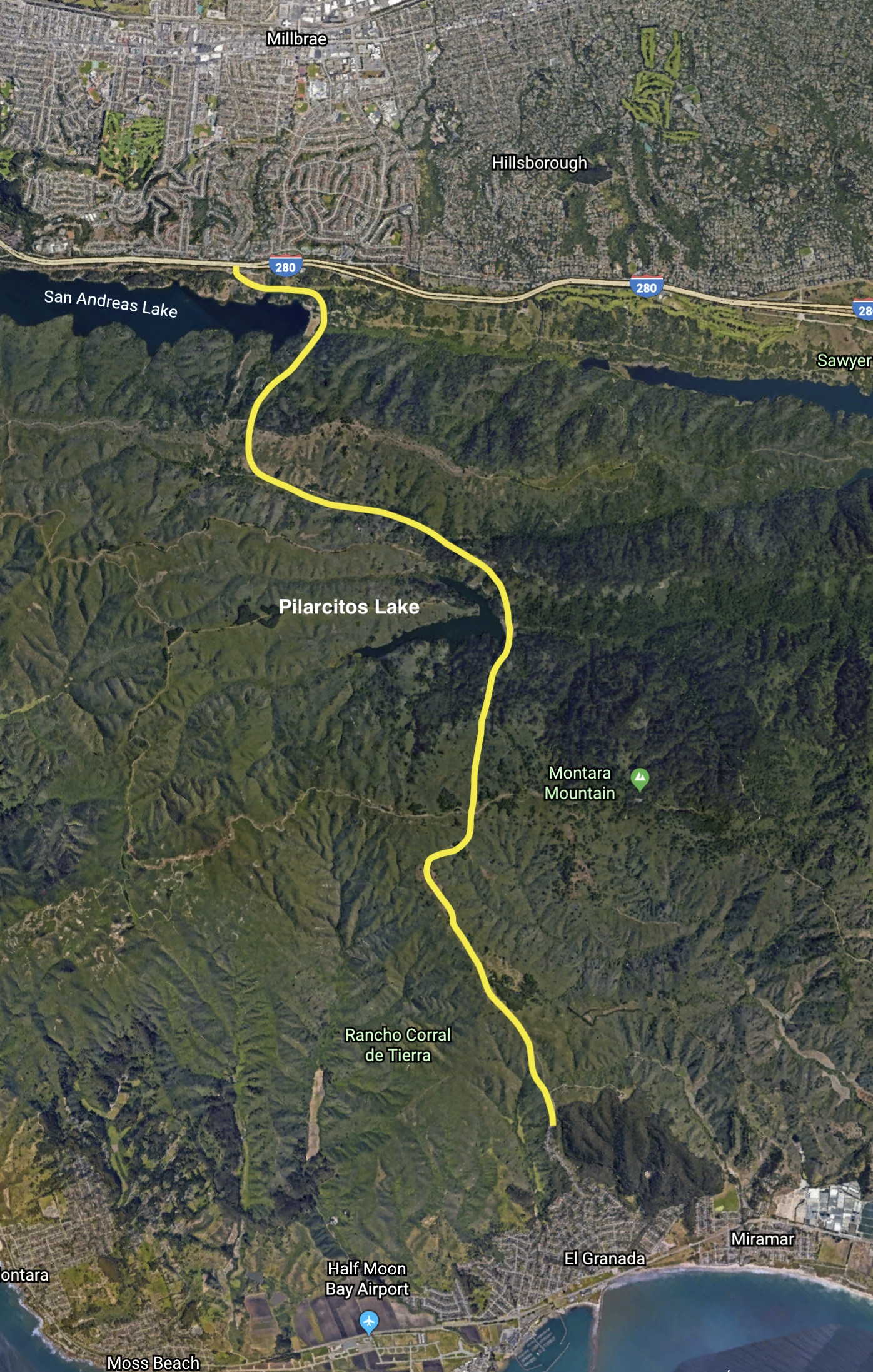

As the crow flies, Millbrae, California, which sits on the bay side of the northern San Francisco Peninsula, is roughly eight miles from the town of El Granada, which sits on the Pacific. To drive from Millbrae to El Granada, however, depending on which route you choose, and how much you like to meander, will take you between twenty and twenty five miles, but that was not always the case. When the first roads on the Peninsula were built, most of which are still in use, there was a road that made a near beeline from Millbrae due southwest to El Granada. It still exists today.

The landscape that surrounds this road has changed a lot since the 1860s. The stories of how and why it changed tell a narrative that brought the region of Northern California from the place where the Old West met the sea to what we know as the modern world. There are more stories than we can go over here, but if recounted correctly, they tell a tale of the landscape surrounding this road that revolves around the two life-bloods of any society: money and water.

At 280 and Larkspur Drive, near the we stern end of Millbrae Avenue, is an entrance to the most popular park in San Mateo County, the Sawyer Camp Trail. A short walk on this trail will take you to a beautiful, interesting, and historically important place, the San Andreas Dam. Built in 1868, it dammed the creek that ran north-south down the resort town of Crystal Springs, and acted as a bridge across the valley for travelers heading west across to El Granada. The scenery here is serene, yet the dam’s harnessed power of both humans and nature balances squarely on the San Andreas Fault. A feat of engineering for its time, the earthen dam proudly withstood the 1906 Earthquake with only slight damage.

stern end of Millbrae Avenue, is an entrance to the most popular park in San Mateo County, the Sawyer Camp Trail. A short walk on this trail will take you to a beautiful, interesting, and historically important place, the San Andreas Dam. Built in 1868, it dammed the creek that ran north-south down the resort town of Crystal Springs, and acted as a bridge across the valley for travelers heading west across to El Granada. The scenery here is serene, yet the dam’s harnessed power of both humans and nature balances squarely on the San Andreas Fault. A feat of engineering for its time, the earthen dam proudly withstood the 1906 Earthquake with only slight damage.

Just up the road from the dam, near the top of the ridge, lay the dairy farm of W.J. Fifield. Fifield and his brother had been operating the dairy farm as far back as the mid-1860s. As the dairy was situated on the road to the coast, it had to routinely send workers into the town of Millbrae for supplies and business affairs. Such was the case the evening of Tuesday, June 22, 1886, when an employee of Fifield’s, a Mr. Joseph Sine, was driving a horse-drawn wagon back to the Dairy Farm. Unbeknownst to Sine, his companion on the wagon, a man named Peter Coetaneno, had plans to ambush him. At the dam, Coetaneno asked Sine  to let him off the wagon, preparing to do something that would eventually make him a wanted man. The next day, the Daily Alta, a newspaper out of San Francisco, reported that W.O. Booth, a lawman out of San Mateo, had issued a warrant for Coetaneno, it reads:

to let him off the wagon, preparing to do something that would eventually make him a wanted man. The next day, the Daily Alta, a newspaper out of San Francisco, reported that W.O. Booth, a lawman out of San Mateo, had issued a warrant for Coetaneno, it reads:

…”calling for the arrest of a Greek named Peter Coetaneno, who is wanted on a charge of murder. The wanted man is about thirty years of age, looks like a Spaniard, weighs about 145 pounds and stands about 5 feet 7 inches high. His hair and moustache are jet black, and on his nose is a peculiar scar. When last seen he wore a black suit of clothes and soft felt hat. Coetaneno left Pilarcitos Lake about midnight, June 21st, and presumably started for San Francisco.”

When Peter Coetaneno stepped off the wagon, he turned and shot Joseph Sine twice in the chest. The next day’s Sacramento Daily Union described the wounds in detail:

…”one (bullet) took effect in the breast, striking the rib, passed around the body and lodged in the muscle of the back. The wound is not necessarily fatal. The officers of San Mateo County are scouring the hills for the would-be murderer. Mr. Fifield says it was a preconcerted plan to kill Sine; that Castino had been waiting two hours on the road before he got on the wagon.”

Sine must have lived long enough to tell his story, though it’s not clear if he survived: the Daily Union reported “Sine as doing well, and will likely recover” and the Daily Alta reported the story as murder. Notably the Alta and the Union spelled the assailant’s surname differently, and neither newspaper (to my knowledge) ever reported Coetaneno’s (or Castino’s) capture. As for Fifield’s Dairy Farm, the excrement from the cows, among other things, was enough of a nuisance that in March of 1902, the Spring Valley Water Company took him to court. Later the  Water Company purchased his 1,107 acre farm altogether.

Water Company purchased his 1,107 acre farm altogether.

By the 1890s, the Spring Valley Water Works was a monopoly in San Francisco, but it was the 1860s when it initiated its enterprise in Pilarcitos Valley, west of Fifield’s Dairy. When Spring Valley’s first engineer, Colonel A.W. Von Schmidt, oversaw the creation of Pilarcitos Lake Reservoir in December of 1863, it was such a success that the dam was raised in 1867 to keep up with demand. The waters of Pilarcitos Lake were brought to Laguna Honda in San Francisco via a redwood flume, and allowed the thirsty city to grow at a time when potable water was being sold by the barrel, for gold.

Over time, Pilarcitos Lake became a destination location for San Francisco’s well-to-do and residents of the Peninsula for daytrips, picnicking and fishing. A lakeside cabin was built to host visitors, and water quality was analyzed and praised for its ability to be use in brewing beer. Muskellunge Pike were brought in from the mid-west for the enjoyment of anglers. Fortunately for any native species, the invasive predatory fish never took hold as the Daily Call newspaper reported in 1893. There was serious talk of building an electric trolley line to L ake Pilarcitos in 1912. The lake was advertised as a destination spot in San Mateo County by the San Mateo Chamber of Commerce as late as 1930.

ake Pilarcitos in 1912. The lake was advertised as a destination spot in San Mateo County by the San Mateo Chamber of Commerce as late as 1930.

In the time period between 1910 and 1926, the Spring Valley Water Company was openly advertising to the public the glory of the locales owned by Spring Valley. Willam Bours Bourn II and Willam Ralston, the company’s largest stockholders, stood to make a lot of money if their stock in Spring Valley was purchased by the city of San Francisco. In 1910, Bourn commissioned his friend Willis Polk to design a water temple, based on the Temple of Vesta in Italy, at the east end of Niles Canyon in Sunol. In an attempt to appeal to SF voters, Spring Valley’s own magazine SF Water described the beauty, recreational activities and history of the lakes at Pilarcitos, Stone Dam, San Andreas and Crystal Springs. In the July 1926 SF Water magazine, an author identified only as “Contributed” described Lake Pilarcitos in one of the most beautiful run-on sentences of all time:

“Here is the most beautiful portion of California, unspoiled by man, a park of Nature’s own making, where beings animate and inanimate reach the perfection for which they were intended; a land of fountains, streams and waterfalls and lakes, of fern and fruit and flowers, of trees and thickets, of sunlight and shadow, of peace and plenty.”

Fountains were built at Lake Pilarcitos and at the Sunol Water Temple across the bay, created to quench the thirst of the visiting public that Bourn and Ralston were so eagerly courting. These opulent fountains still exist today. Like so many other relics of the Spring Valley Water Company and the era at large, they were designed to appear as though from antiquity. They are four-sided, and each side has what appears to be a rather menacing face. In a time still connected to the settling and taming of the west and the grandiose ethos of Manifest Destiny that drove it, these ornate relics embody the Spring Valley’s own subtle ethos that building great infrastructure for civilization somehow connected them to the great civilizations of the past. Through email, I was able to make contact with UC Berkeley professor and author of “Imperial San Francisco” Dr. Gray Brechen. The Professor surmised:

“The fountains and their faces were probably designed by Willis Polk who was William Bowers Bourn’s court architect. He designed the Sunol Temple as well as other facilities for the Spring Valley Water Company including its headquarters on Mason Street. There you will see terra cotta that mimics water running down the front of the building the way that you see under the faces…”

… “The faces themselves seem to be taken from classical depictions of Neptune and river gods: old men whose beards are running water. Although Polk was not trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he was so good that he may as well have been, and he probably hired others who were since he had one of the leading architectural offices in SF.”

Surrounding Lake Pilarcitos remains an entire network of roads that traverse both north-south and east-west. The roads run along both ridge lines of Pilarcitos Valley and along Pilarcitos Creek. One road followed Pilarcitos Creek to the Pacific in Half Moon Bay, known in the 1860s as “Spanish Town”. The road to El Granada from Lake Pilarcitos heads westward, up the hill and down through what is now the GGNRA National Park of Rancho Corral De Tierra, through private property, and eventually turns into El Granada Boulevard, a public road well-known by residents of the Coastside SF Peninsula.

Today, El Granada is as scenic and beautiful as ever. It hosts surf competitions and festivals; it has hotels and a brewery. El Granada and the surrounding coastal towns have always been beautiful places and today they are a destination for tourists. On the wrong weekend, they may seem crowded, but most of the time El Granada may be described as sleepy. (This is especially true when compared to the scene in Millbrae, where the cars on 101 roar and jetliners scream into and out of SFO.) In that way it is still somewhat similar to the 1860s, when the tourists could travel the road a mere eight miles from the El Camino on the busier bay side for a day at the coast.

The rest of the story >>

The Raker Act of Crystal Springs and more!