|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

OWN VOICE. ~ InPerspective by Gregg Dieguez

That smoke you see and smell is coming from a fire, but there’s more than one issue “hanging fire” here on the Mid-Coast.

Footnotes: to use, click the bracketed number.

Images: most will enlarge for improved readability in a new window when you click on them.

First, there’s the new Half Moon Bay Local Coastal Land Use Plan (LCLUP) – a largely well-written and considered document which is missing a few important things. The first missing item is Water.

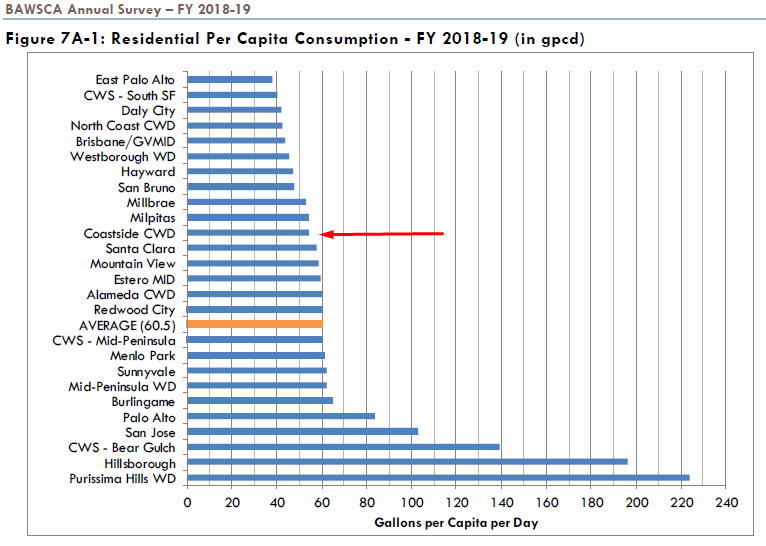

Even before the most recent drought, and before the State’s new Bay-Delta Plan to save the Tuolumne and other rivers by diverting more Hetch Hetchy water to them, CCWD’s most recent Urban Water Management Plan documented a 47% cutback in the 3rd year of a drought[1]. Note that the shortfall scenarios the SFPUC presented and which were used in that analysis are amplified because wholesale customers like HMB get a decreasing percentage of the reduced supplies.

Now, with the Bay-Delta Plan, BAWSCA (the agency which buys Hetch Hetchy Water for CCWD and other regional water systems), forecasts a 58.6% cutback in year TWO of a drought, rising to a 67.6% shortfall by year 7 of an extended drought.[2] And the Climate Crisis is going to ensure we have more long droughts. Exactly what shortfall will result in HMB, which has other local sources of water, will have to be assessed by CCWD in their next Urban Water Management Plan expected in June of 2021. However, the news – for a city which was already responsibly conserving water and paying high prices for it – cannot be welcomed by residents of HMB, or any of the other two dozen water agency clients in San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Alameda counties.

Without a concrete plan for more water supply, including all costs associated, one has to question how a new local development plan involving ANY growth can be published at this time. Further, HMB residents have to wonder what possible benefits to them: as ratepayers, taxpayers, and residents – can result from growth in the Quantity of life in HMB. Shouldn’t the focus be on Quality of life, including Affordability and Security?

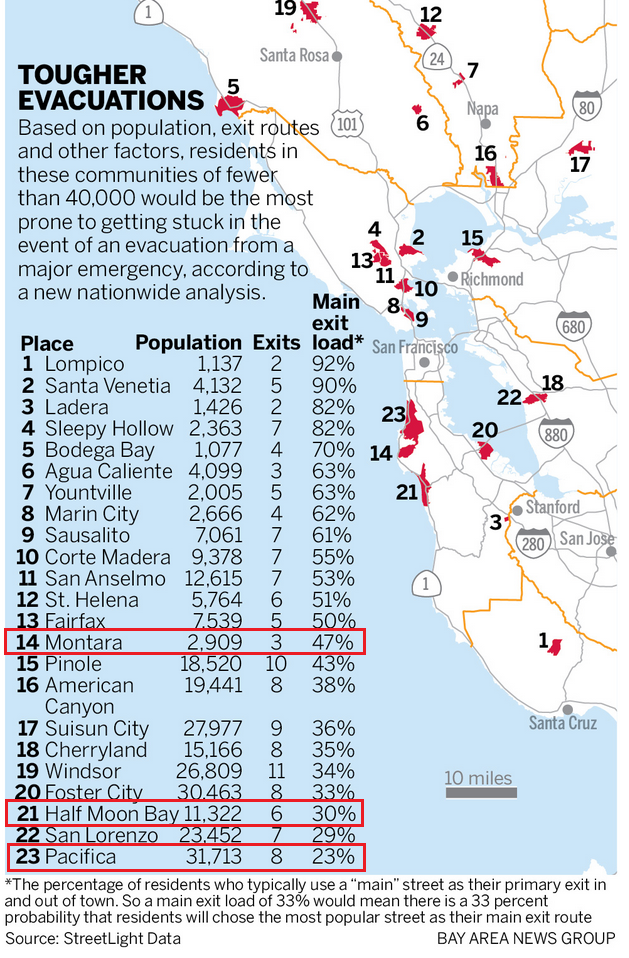

And speaking of Security, the wildfire risks once again evident have to bother Mid-Coast residents. The new Connect The Coastside Transportation Plan (CTC) never addressed evacuation risks, and we know from the tunnel closure last year that our escape routes are far worse than Paradise before its deadly fire. Further, do we have the fire-fighting water storage adequate for the next big fire?

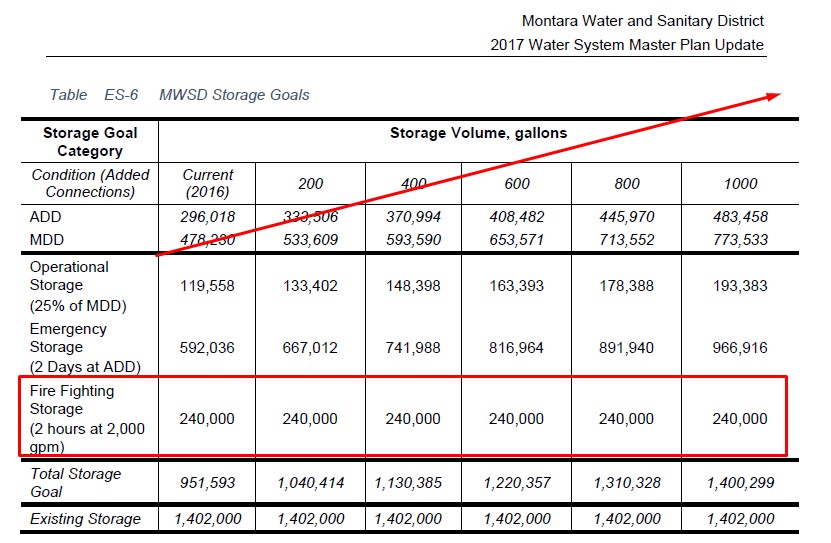

MWSD’s fire fighting storage is 240,000 gallons, and has not grown with population, and is not forecast to grow in the last (2017) Master Plan. [Note in the chart below that the District has 1.4M gallons in total storage, which could be deployed in an emergency.] It has been repeatedly explained to me that 240,000 gallons exceeds Fire Code requirements for a 2-hour “designer fire”. As one Water Agency GM told me “the fire code only requires you to fight one fire at a time”.

CCWD has 4 million gallons of water stored in reserve for fire fighting, sixteen times MWSD. Other water districts routinely have several millions of gallons of fire water storage. With the addition of Big Wave and/or the Mid-Pen Cypress Point developments, there will be multi-unit dwellings (e.g. ‘fourplexes’). Eventually, Big Wave expects commercial tenants. Commercial fires often require 1 million gallons of water to fight. Just based on proposed square footage, CalFire told me two years ago that 600,000 gallons of fire storage will be required for Big Wave. What additional fire-fighting water storage must MWSD build in response to these dense new developments, and who is going to pay for it? While CalFire is responsible for fighting wildfires, not MWSD, I think it is fair to ask whether current fire fighting storage should be expanded, especially when dwellings are next to the worst wildfire hazard area of our County.

And speaking of paying for things, let’s look at the recent trends in Big Wave. I asked the County “how do you know the $1.6 million Big Wave is paying for infrastructure improvements is enough? Where is the worksheet tallying the initial and ongoing revenues and expenses, including eventual replenishment of the assets being created?” And the response was in essence: “we don’t have such a process”. A roundabout at Cypress Avenue will cost about $5.5 million – so Big Wave is at best only funding a traffic light. The County has protected itself for some of the initial Big Wave costs, but has no process to ensure taxes going forward are adequate for the perpetual ongoing costs and asset replenishment requirements?! But wait, there’s more….

This week Big Wave put out an email complaining about the lack of traffic control funding and the cost of the CTC-planned roundabout at Cypress Ave and asking for “a temporary traffic light could be installed at a cost of only $300,000. ” Keep in mind that, with COVID-19, there is no longer a traffic problem at that intersection. In fact, the entire CTC should have been delayed until things stabilize after COVID – rather than planning for $150 million of new transportation stuff – much of which may never be needed. But now Big Wave is asking to immediately spend $300,000 of taxpayer money, which will be a throwaway expense, in anticipation of a problem they will be causing. But wait, there’s more…

On August 20, Big Wave will be presenting a request for reduced sewer connection fees from GCSD. The County has decided that it is a social priority to put this Wellness Center out here, away from hospitals and other essential services the tenants will likely require. But how are the ratepayers of GCSD going to feel if, in addition to the county taxes they pay, and in addition to the traffic congestion they will suffer from the development, they are asked to subsidize the costs of Big Wave?

And what is Big Wave next going to say about the water connection fees in Montara, where the Water Reserves are already ‘under water’ in spite of half a million dollars being moved from Sewer to Water last year? And what are Montara ratepayers going to say about the added fire risk, water storage, and connection fees given that ratepayers – under strong protest – only funded HALF of the water system capital improvements the district requires?

Why isn’t Big Wave financially self-sustaining, and able to pay for the infrastructure it requires? Is Jeff Peck just trying to squeeze all the profit he can from his development? Or is he also a victim of an uncoordinated planning process, forcing him to bump from one obstacle to the next? Ours must certainly be considered a First World County, with accredited professionals staffing major positions of responsibility. Could it be that, in order to favor Real Estate interests, the planning process is intentionally fragmented, to allow developers to divide and conquer one obstacle at a time, and to obscure the full and future costs of development until they are forced onto an unsuspecting public?

There are two themes running throughout this article. The first is Risk – to health, safety, quality of life, and affordability. The second is the fragmented, incomplete, and uncoordinated nature of the County’s planning. It is understood that every city and agency involved in development gets a voice. What is hard to understand is that there is a governing intelligence behind the planned population expansions in San Mateo County. Unless residents force changes to existing plans, one thing seems clear: residents are going to pay for any growth with their safety, money, and quality of life.

More From Gregg Dieguez ~ “InPerspective”

Mr. Dieguez is a semi-successful, semi-retired MIT entrepreneur who causes occasional controversy on the Coastside, and is now a candidate for the MCC. He lives in Montara. He loves to respond to comments.

As a resident of Montara and a retired economic developer for countries in Europe and Asia I found that most developers focused on the short term and never, yes never on the long term. A clean approach to development was often sufficinet to persuade authorities and the public to approve a project. The rub came when the financial details of the long term were explained: who would pay for the longterm maintenance of the infrastructure; where would the water come from; and were transportation, shopping, and density considered in the plan?

Enough said here.