|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

GCSD HISTORY. From Granada Community Services District’s (GCSD) Director Barbara Dye.

A Sliver of Open Space on the Coast

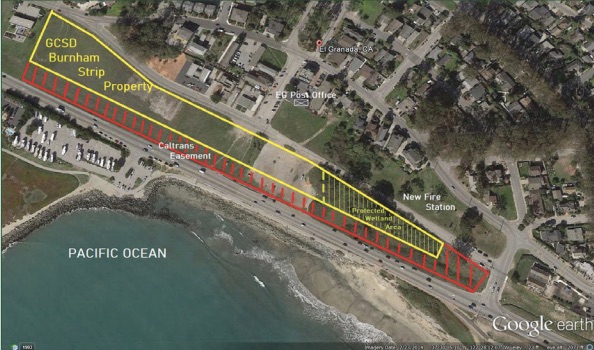

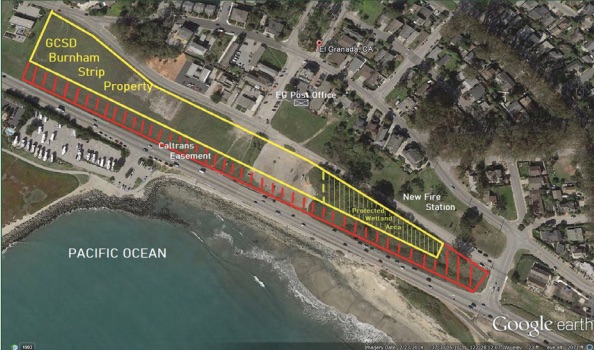

A Sliver of Open Space on the Coast – The area we call the Burnham Strip is on the landward side of Highway One, across from the Harbor and Surfers’ Beach. It runs from Coronado Drive, along Obispo Road and Avenue Alhambra, to Capistrano Road.

In the Beginning

In the Beginning – This story begins a very long time ago, about 100 million years. The oldest rock in this area, the Montara Mountain granite, was formed near the Mojave area in southern California, and carried north along a series of parallel faults. The infamous San Andreas fault extends along the Crystal Springs reservoir, while the San Gregorio/Seal Cove fault passes offshore and then through Pillar Point marsh.

The Montara Mountain Granite originally cooled from a magma chamber, and is made up of quartz and feldspar, with some metallic minerals. The quartz in this rock supplies the material for the area’s white sand beaches. Because it is very solid and homogeneous, it does not shake as much as rocks with layers or sediments and provides a relatively strong base for homes in earthquakes.

While the coast was moving northward, ocean levels were rising and falling, depositing marine sediments on top of the granitic rocks. These are shales, mudstones, conglomerates, and sandstones, some with many marine fossils – bones of marine mammals, shells, and more. The visible deposits on the area we call the Strip are relatively recent and were left by those moving shorelines. Covering the surface are alluvial fan deposits thousands of years old, including loams with high water-holding capacities that cause surface cracks during extended dry periods.

Humans Arrive on the Scene

Humans Arrive on the Scene – People most likely came to California at least 12,000 years ago (there is older evidence but it is much disputed). The ancient shoreline was then miles farther west so evidence of longer habitation is mostly lost. Archaeological evidence indicates ancestral Ohlone arrived in the San Francisco Bay region–depending on location–somewhere around 1500 years ago, displacing earlier populations. The El Granada area was occupied by Indians for many centuries prior to the European arrival. They lived generally along perennial and seasonal streams and along the ocean coast.

The best current evidence indicates that this area was held by the Chiguan tribelet, who had several villages in the area. One was located at Pilarcitos Creek, another near Pillar Point, and a third was probably in Montara. None are known in or adjacent to the Burnham Strip, but inhabitants of the area undoubtedly traveled along the coast and most likely made use of it there for hunting, fishing, or just to enjoy the view of what is now called Pillar Point. Like other native Californians, the Ohlones managed their environment to improve it for their use. They burned grass and brush lands annually to improve forage for deer and rabbits, keep the land open and safer from predators and their neighbors, and improve productivity of the many resources they used.

The Arrival of Europeans

The arrival of Europeans – The Spanish Portola expedition marched through this area on October 30th, 1769. The diaries of Father Juan Crespi noted, “About nine o’clock in the morning we set out … along the shore, carrying firewood from the creek here [Pilarcitos Creek], where there is a little, as the scouts reported they had seen no wood where they explored. Close to the shore ran tablelands and flat-lying hills of very good soil and grass, though the latter all burnt, for the natives burn off everything in order for a better yield in the grass-seeds they eat. On going about a league, we came to the point [Pillar Point] … which makes a good [bay] here. It would be a fine place for a town, but there is not a stick of wood anywhere about.” The early Spanish explorers did not mention encountering natives between Pilarcitos Creek and Pacifica.

Later European arrivals labeled these people “Costanoans,” from the Spanish “costanos” or coastdwellers. The Native Americans who controlled the San Francisco and Monterey Bay regions (including the MidCoast) at the 1769 Spanish invasion are now most commonly called “Ohlone,” a name derived from a coastal village between Santa Cruz and Half Moon Bay. Some Indian descendants still prefer “Costanoan,” while others prefer Ohlone or identify with more specific tribelet names.

Corral de Tierra

Corral de Tierra – After the Mission in San Francisco was established in 1776 and continuing through 1833 when their last roundup was held, the Mission Dolores ran cattle on this coastal area. They called it “Corral de Tierra,” or the earth corral, because the mountains hemmed in the herds and kept them in one general location. In 1839 the Mexican Governor granted all the land from Medio Creek to Montara Mountain to Francisco Guerrero-Palomares, a Mexican soldier who had served in the army. He lived in San Francisco, but built an adobe home (now gone) on Denniston Creek, where the brussels sprouts fields now lie. In 1851, in a shocking event, he was murdered in the city because of a land dispute, and the land passed to his widow.

James Denniston, an American who had been a soldier and gold prospector, married Josefina Guerrero-Palomares and became the owner of the land grant she had inherited. He began farming the coastal areas, with grain, potatoes, vegetables, and dairy, but had difficulty getting his produce to market in the city. When Denniston died in 1869, his land was divided between his widow and her two sons by her first husband. She retained the area that is now El Granada, but over the next few decades the land was divided into smaller parcels and sold. The farmers who bought them planted eucalyptus trees as windbreaks and to provide a landscape with tall trees that looked more like their home countries. Enthusiasm for tree planting grew throughout the 1870s, with the establishment of nurseries and the government providing financial incentives to add trees. Eucalyptus trees from Australia were touted for their speed of growth and their ability to absorb water (thus reducing swamps and the dangers of malaria) and were thought to be a good source of masts for ships and timber for building construction.

Train Time

Train Time – The Ocean Shore Railroad was incorporated in 1905 to develop a railroad line between San Francisco and Santa Cruz. The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 destroyed a great deal of the work that had been done, but construction continued. On June 21, 1908, the first train arrived in what is now El Granada. The line went from the Granada North station at the corner of Capistrano and Alhambra (still standing, but converted to a restaurant and apartment), along the east side of Avenue Alhambra and Obispo Road, between the old fire station and the hardware store, west of the post office, and to the Granada South station where the elementary school is now. The plan was to prosper by selling land to develop new communities, transporting timber and produce back to the city, and bringing visitors and new residents to the Coastside, along with the materials needed to build homes.

The grandest of the towns the Railroad planned along the route was Balboa (now El Granada). They bought five parcels for $60,000, acquiring 1,271 acres. They wanted the best for Balboa, so they hired Daniel Burnham to provide the design.

“El Granada, A Synonym for Paradise!”

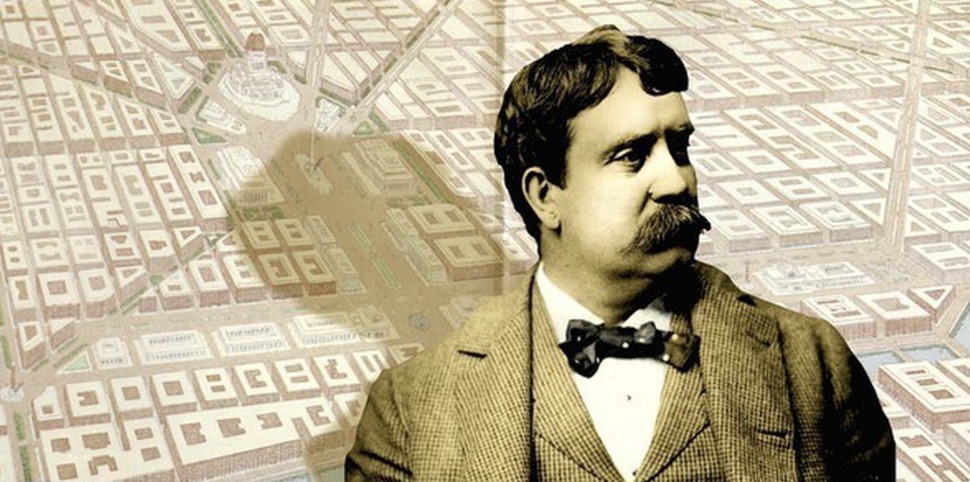

“El Granada, A Synonym for Paradise!” – Daniel Burnham was the most famous landscape architect in the western world at the turn of the 20th century, having designed the Chicago World Columbia Exposition in 1893. He was the leader, along with Frederick Law Olmstead, of the “City Beautiful Movement,” which recognized the physical and aesthetic limitations of rapidly growing and unplanned cities. The movement advocated for well-planned cities, with services, parks, and attractive boulevards, and was very influential.

Burnham hired young English architect Edward Bennett to help with the project. It was Bennett who visited the site and provided the maps, photographs and models Burnham studied in his Chicago office. They submitted a plan in October 1906 for the oceanfront area and the layout of the streets. The Railroad Company president said “in the years to come, Granada will rank with the most beautiful cities in the world.” Historian Barbara VanderWerf, the author of “Granada, a Synonym for Paradise,” said that the fact that El Granada “is the only Daniel H. Burnham town built in the United States” is enough to make it “a national treasure.”

The plan for coastal development called for train stations with a casino in between (not for gambling, but a place of entertainment, with a theater and a ballroom), two piers, and walkways. Above this were terraces with public parks, more-or-less where a park is being proposed now. Burnham recommended planting trees, but not the eucalyptus the railroad company installed in huge numbers. He favored moderate growth trees along the streets such as acacias, aruacarias, pepper, locust and palms.

The plan for coastal development called for train stations with a casino in between (not for gambling, but a place of entertainment, with a theater and a ballroom), two piers, and walkways. Above this were terraces with public parks, more-or-less where a park is being proposed now. Burnham recommended planting trees, but not the eucalyptus the railroad company installed in huge numbers. He favored moderate growth trees along the streets such as acacias, aruacarias, pepper, locust and palms.

There were more than 47 tracts along the railroad line offering lots in new communities. Customers could take a free train ride, followed by a complimentary luncheon and a real estate presentation. In this area construction began on streets with curbs and gutters (still visible in some places), sewer and water lines, and sidewalks. By 1909, the town had been renamed Granada, called a “Synonym for Paradise” in the real estate materials, which urged people to “shake off the tedious grind of the daily commonplace – be happy next Sunday at Granada.”

Although the plan had been to call the new community Granada, in about 1909 the postmaster (who was also the owner of a hotel he had named Hotel El Granada) recorded the name as El Granada, even though the word “granada,” meaning pomegranate, is feminine and the city in Spain is just Granada. Through the years there have been discussions about renaming the town, but El Granada it remains to this day.

Photographs of opening day and arriving visitors in 1908 show compacted soil along the train tracks, with very little vegetation. By 1910, the streets of the surrounding town had been laid out, but photographs show just coastal plains and hills, with no significant vegetation. A temporary train station was built which was later moved to the top of Avenue Portola to be used as a clubhouse. It is still there as a private home.

A large open space was created on both sides of the median in Avenue Portola and on the land near the ocean. It was known as Plaza Alhambra, and was the spot where visitors arrived, although the railroad company never built the magnificent new depot it had been promising. The Granada bathhouse, a precursor to the planned casino, was built on the beach west of Avenue Portola below low bluffs. It was reached by walking across a grassy meadow. The new attraction had rooms for gatherings and for changing into bathing attire, and in 1910 three hundred people attended its grand opening.

Although the plan was for the railroad to be the major way people moved along the Coastside, its irregular schedule and slow speed time led travelers and farmers to continue to use the inadequate road alongside the railway line. In 1913 the County decided to build a new road along the Coastside generally on the route of the old road, with a section built where Obispo Road runs today.

Farming Replaces the Railroad

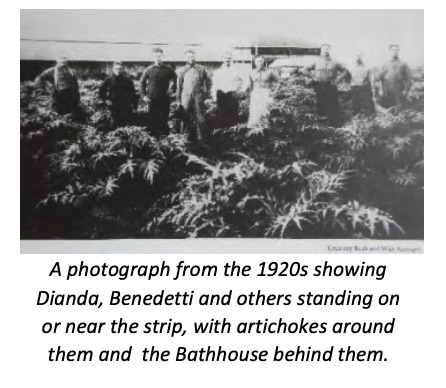

Farming Replaces the Railroad – As time went on, interest in Coastside real estate diminished and the automobile became the primary method of transportation along the coast. As a result, the railroad’s financial situation worsened considerably; their investments in infrastructure had been expensive, and sales were not covering their costs. In 1920, the California Railroad Commission approved abandonment of the line. By the end of 1921 most of the tracks were dismantled and sold. The Ocean Shore Railroad Company also sold off many of its remaining lots, including tracts of coastal land to local farmers Giovanni Patroni and Dante Dianda. They planted the area with crops, especially the artichokes for which the area had become famous. The bathhouse was used for storage, and eventually washed into the ocean.

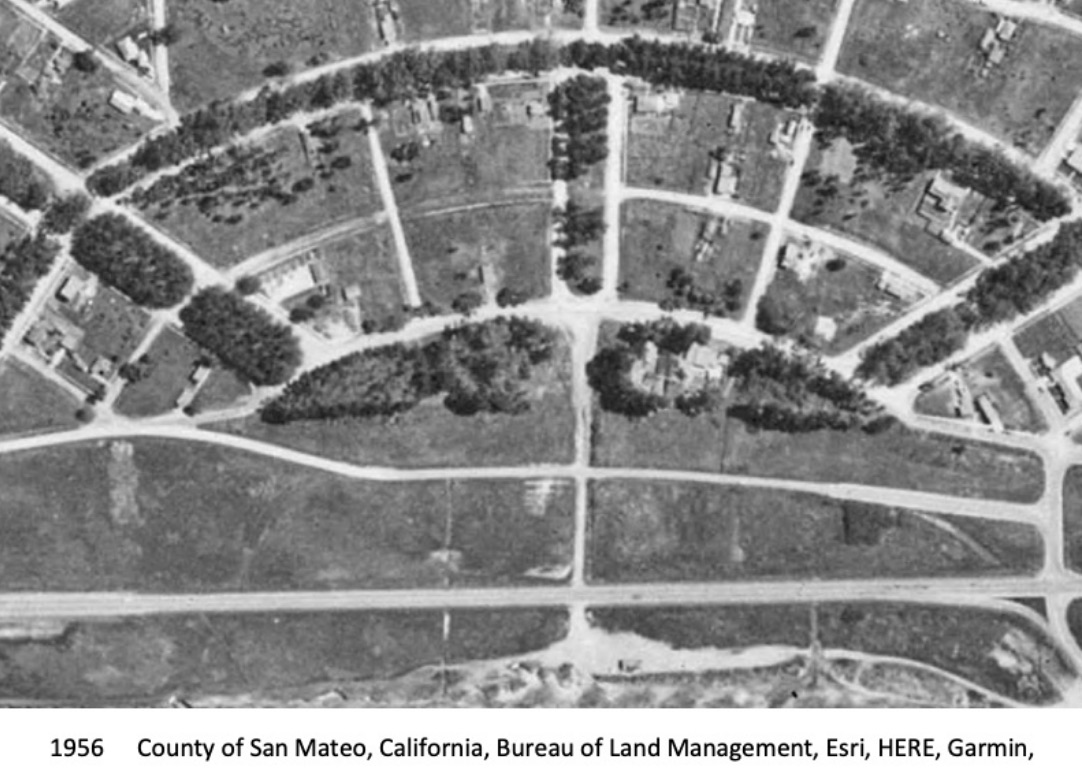

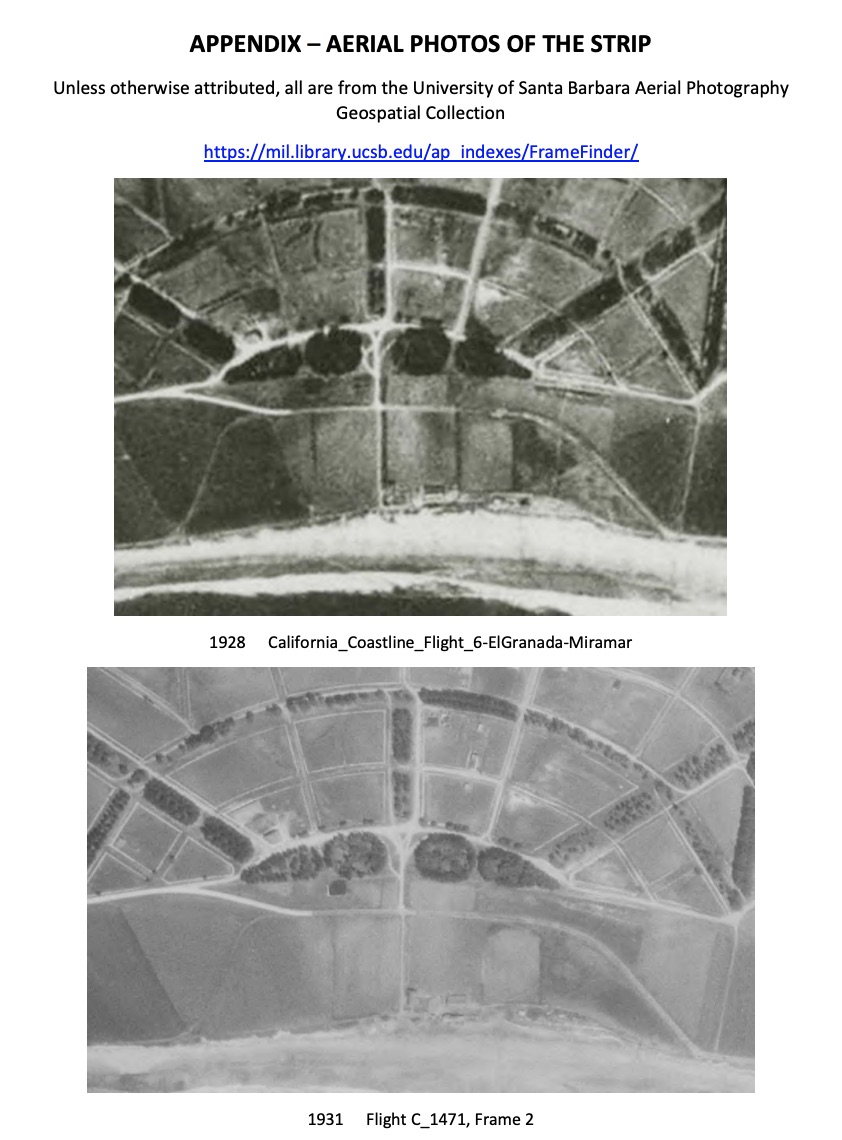

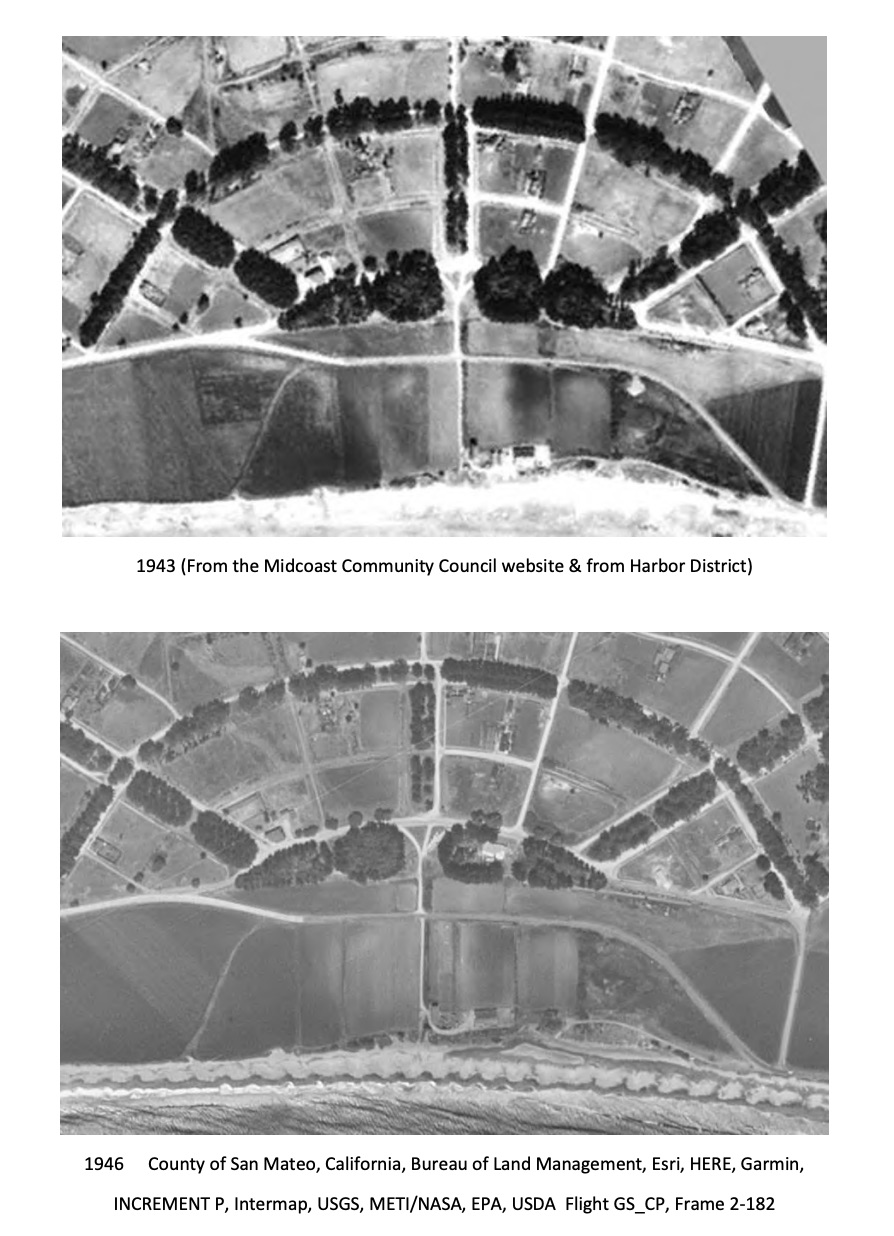

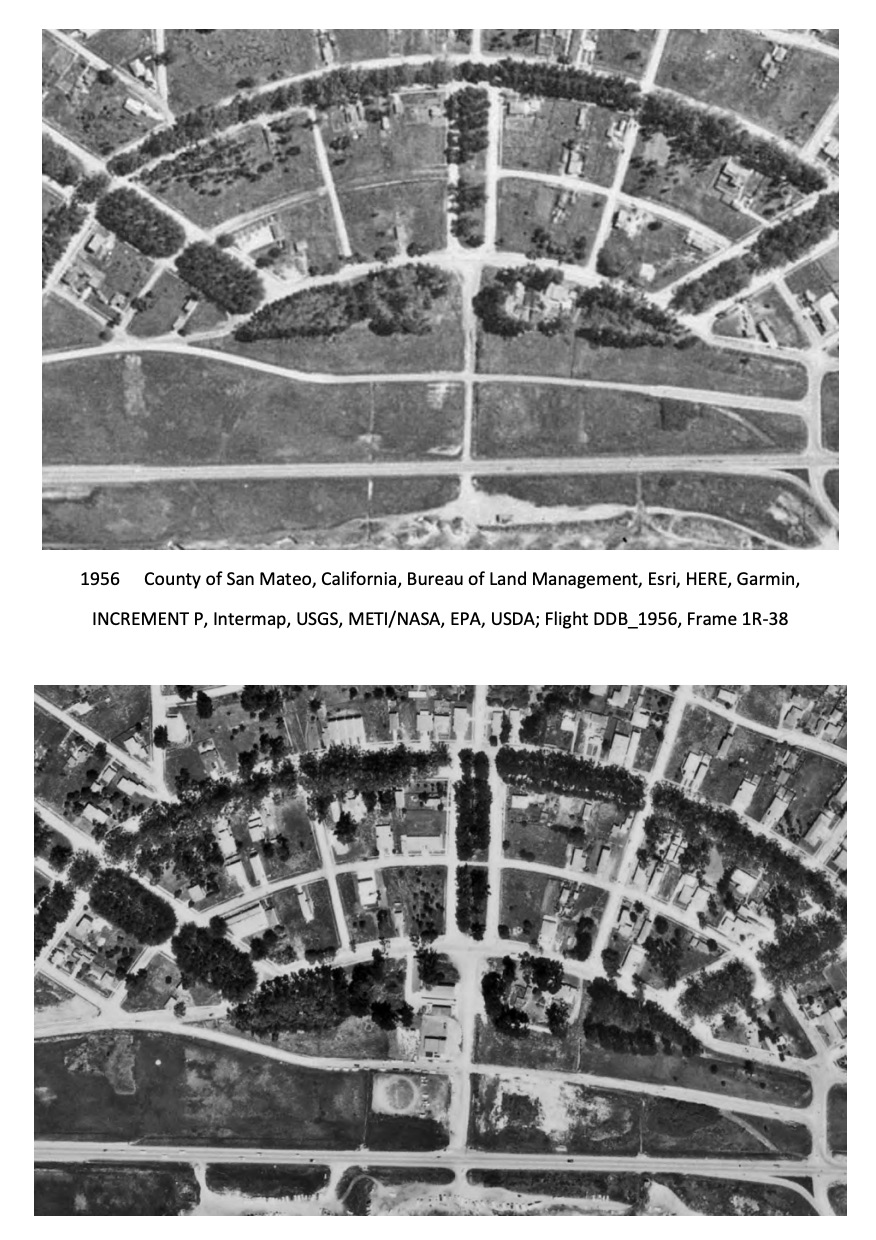

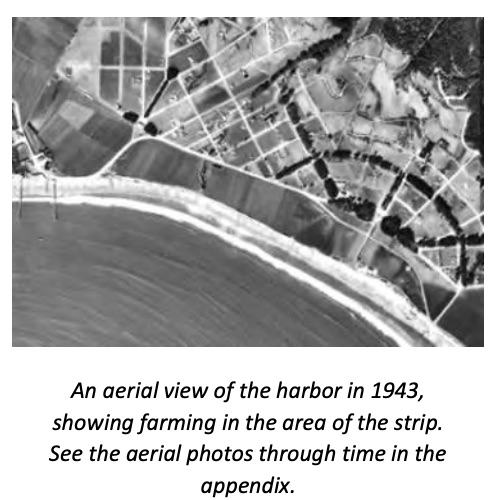

During the decades after 1920, there was little activity in El Granada. The development to the west and north, Princeton-by-the-Sea, was more successful than El Granada. There were numerous hotels and restaurants, and a small port and piers for shipping goods and produce to and from San Francisco. During Prohibition, the coastal restaurants were lively places, as the coast provided suitable locations to bring liquor in by sea and they were out-of-the-way enough to avoid observation. The deep canyons provided spots for illegal distilleries in the hills. In El Granada individual lots were developed for single-family homes, but there was little commercial development for the next few decades. The Hotel El Granada welcomed visitors, and there was one store. An aerial photo from 1928 shows large trees between Plaza Alhambra to the east and the Strip property, and another from 1931 shows the strip as cultivated, probably with artichokes.

During the decades after 1920, there was little activity in El Granada. The development to the west and north, Princeton-by-the-Sea, was more successful than El Granada. There were numerous hotels and restaurants, and a small port and piers for shipping goods and produce to and from San Francisco. During Prohibition, the coastal restaurants were lively places, as the coast provided suitable locations to bring liquor in by sea and they were out-of-the-way enough to avoid observation. The deep canyons provided spots for illegal distilleries in the hills. In El Granada individual lots were developed for single-family homes, but there was little commercial development for the next few decades. The Hotel El Granada welcomed visitors, and there was one store. An aerial photo from 1928 shows large trees between Plaza Alhambra to the east and the Strip property, and another from 1931 shows the strip as cultivated, probably with artichokes.

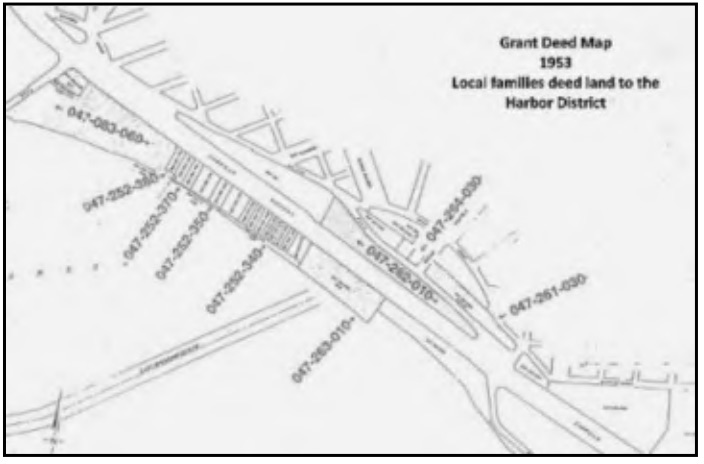

In 1933 the San Mateo County Harbor District was formed by the County Board of Supervisors, but the Depression stopped any plans for building a protected harbor. In 1953, three women from the Dianda family – Sylvia Dianda, Agnes Tolomei, and Rose Schmidt – transferred three parcels to the Harbor District, reportedly for free. The parcels were the strip, the lot on the northwest corner of Obispo and Portola, and the long lot starting next to the post office and continuing to where the new fire station sits.

In 1933 the San Mateo County Harbor District was formed by the County Board of Supervisors, but the Depression stopped any plans for building a protected harbor. In 1953, three women from the Dianda family – Sylvia Dianda, Agnes Tolomei, and Rose Schmidt – transferred three parcels to the Harbor District, reportedly for free. The parcels were the strip, the lot on the northwest corner of Obispo and Portola, and the long lot starting next to the post office and continuing to where the new fire station sits.

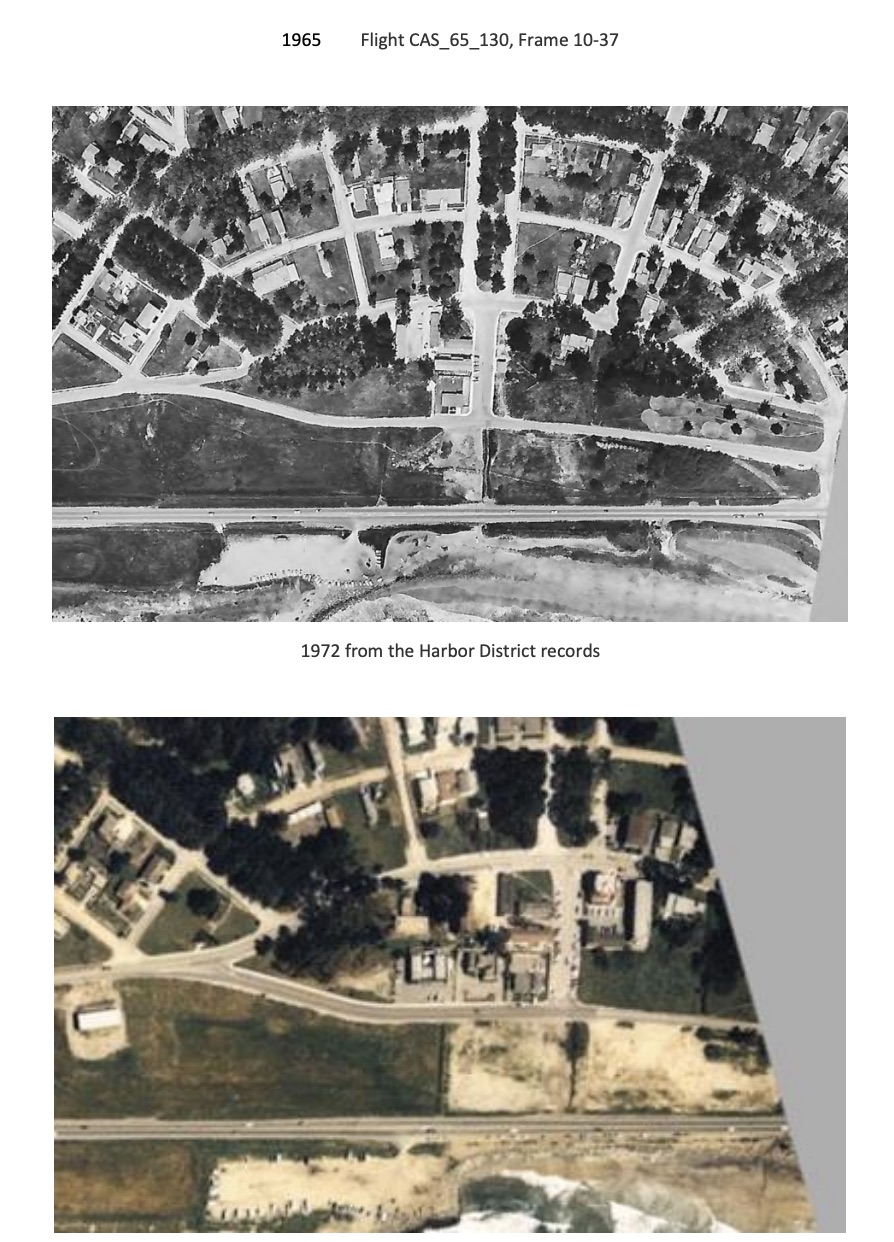

Changes on the Coastside

Changes on the Coastside – On April 1, 1946, a tidal wave swept through Princeton leaving boats stranded. It led to an increased interest in adding a breakwater to the harbor. Erosion continued on the bluffs, and in 1948 the Army Corps of Engineers authorized two breakwaters. A new alignment of Highway One was built in 1949 and 1950 inland of its original location. That project also reconfigured the streets around the Strip, moving Obispo so it connected to Coronado rather than crossing the Strip.

In 1958 the County formed three sanitary districts. Granada Sanitary District (GSD) was formed to provide sewer services for the El Granada area. When Half Moon Bay incorporated in 1959 it included parts of Miramar and all the beachfront property in front of the Strip, although those areas remained in the sewer district. In 1961, the Harbor District was granted the land where the harbor is now; the breakwaters were built in 1959-1961 along with other harbor facilities.

In 1958 the County formed three sanitary districts. Granada Sanitary District (GSD) was formed to provide sewer services for the El Granada area. When Half Moon Bay incorporated in 1959 it included parts of Miramar and all the beachfront property in front of the Strip, although those areas remained in the sewer district. In 1961, the Harbor District was granted the land where the harbor is now; the breakwaters were built in 1959-1961 along with other harbor facilities.

By the early 1960s, the Henry Doelger Corporation owned approximately 8,000 acres just north of El Granada, and began planning for tens of thousands of homes in the area. Only one tract was built by Doelger (now called Clipper Ridge), but then his land was sold to the Westinghouse Corporation, which wanted to develop a city of 200,000 people along the Coastside, so the threat remained.

Inspired by activists from every corner of the state and supported by concerned residents who wanted the California Coast protected, Proposition 20, the “Save the Coast” initiative was passed in 1972, creating the California Coastal Commission. The 1976 Coastal Act made it permanent and set up processes to review all proposed development on the coast and issue permits for appropriate projects.

In 1976 as a result of the Clean Water Act, the federal government required the three coastal sewer agencies to collaborate on one treatment plant. The Sewer Authority Mid-Coastside (SAM) was formed as a Joint Powers Agreement (JPA) between the Granada Sanitary District, the Montara Sanitary District, and the City of Half Moon Bay. The JPA created SAM to build and operate a commonly owned wastewater treatment plant located in Half Moon Bay to benefit all three agencies. Most of the funding was provided by the Federal government. The following year, under pressure from concerned citizens, the Granada Sanitary District moved to halt County planners from unilaterally changing regulations to allow sanitary services outside designated urban zones. This forced development to stay within the subdivided urban boundaries of El Granada, rather than in the open spaces.

In 1976 as a result of the Clean Water Act, the federal government required the three coastal sewer agencies to collaborate on one treatment plant. The Sewer Authority Mid-Coastside (SAM) was formed as a Joint Powers Agreement (JPA) between the Granada Sanitary District, the Montara Sanitary District, and the City of Half Moon Bay. The JPA created SAM to build and operate a commonly owned wastewater treatment plant located in Half Moon Bay to benefit all three agencies. Most of the funding was provided by the Federal government. The following year, under pressure from concerned citizens, the Granada Sanitary District moved to halt County planners from unilaterally changing regulations to allow sanitary services outside designated urban zones. This forced development to stay within the subdivided urban boundaries of El Granada, rather than in the open spaces.

The Community Joins Together to Preserve the Quality of Life

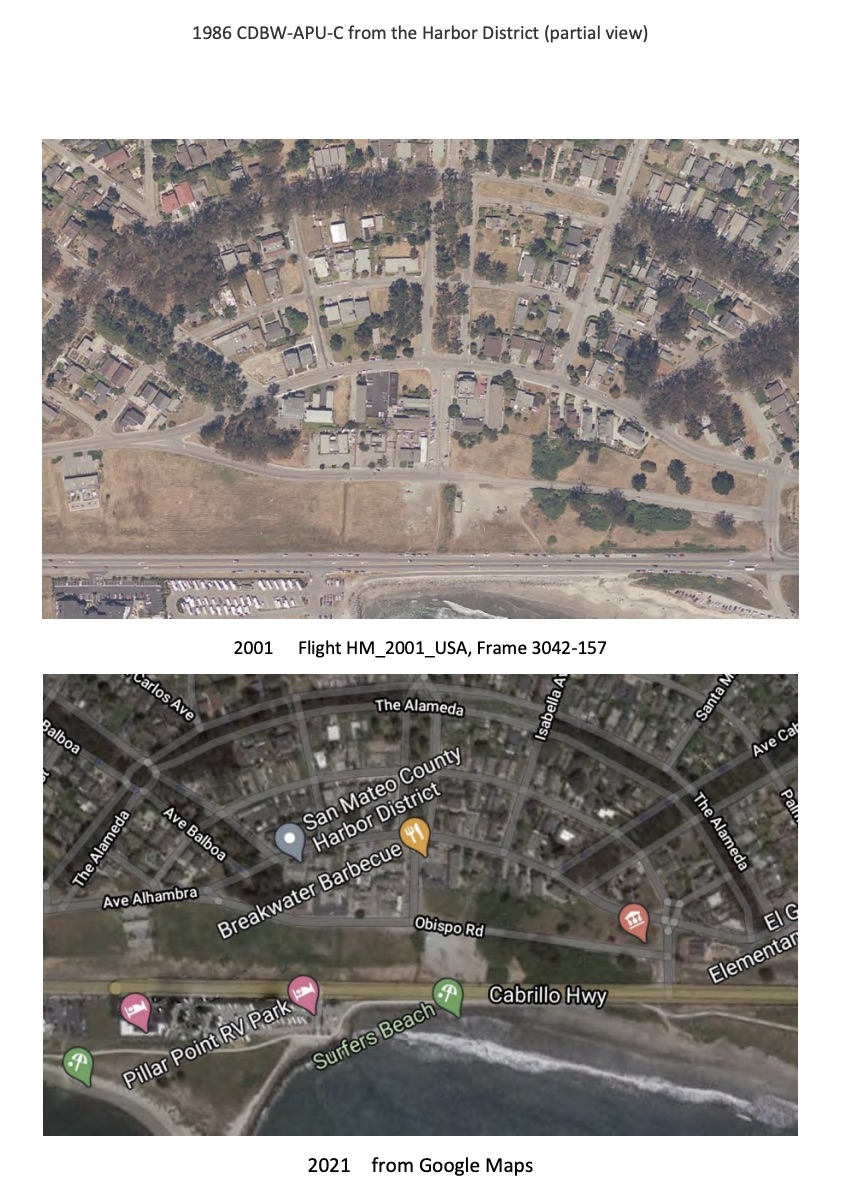

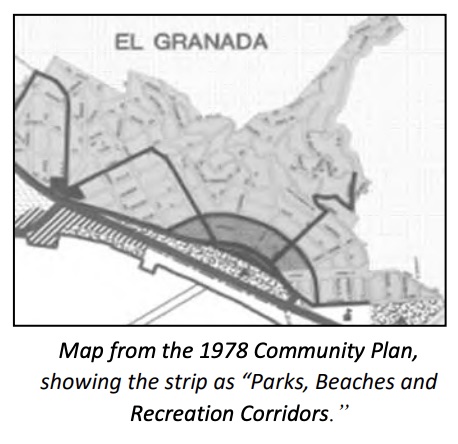

The Community Joins Together to Preserve the Quality of Life – Although dates don’t tell the whole story, the list of plans that were passed at the end of the last Century is a critical part of the history of land preservation in the mid-Coast. Starting in 1972 with the San Mateo County Planning Committee, area residents worked with the County to create the Montara-Moss Beach-El Granada Community Plan, approved in 1978. One of its goals was to “provide park facilities for use by local residents in each community and establish a system for financing them.” Many more proposals and plans were developed, including a Local Coastal Program in 1980 that showed the strip as “General Open Space.”

Throughout the next two decades, the community continued to advocate for preservation of the Strip. However they could not stop the County from allowing one property owner on the Strip to build a warehouse for a plant nursery (which became Picasso Preschool) and construction of a private home. Alarmed by these development, multiple organizations began working toward the goal of preserving land in El Granada. This included Midcoast Park Lands (MPL), started by Fran & Larry Pollard to preserve Quarry Park, but which also advocated for preservation of the strip. That group successfully lobbied the County to place an initiative on the ballot to create a Community Services District. The measure passed, but the accompanying tax to support it did not, so both measures failed.

About the same time, the Burnham Strip Committee (BSC), led by Leni Schultz, was working “to acquire and preserve the entire Burnham Strip as parkland/open space for the Community.” It continued pushing for a Community Services District in El Granada. A group called Park Alternatives for Granada (PAG) became active in 2003, and a Midcoast Park and Recreation Task Force involving the County recommended developing the strip with informal turf areas, a rest room, and miscellaneous improvements, estimating that it would cost $850,000. However, the Harbor District (which still owned it) continued to propose various schemes, including building a fire station and residential housing.

About the same time, the Burnham Strip Committee (BSC), led by Leni Schultz, was working “to acquire and preserve the entire Burnham Strip as parkland/open space for the Community.” It continued pushing for a Community Services District in El Granada. A group called Park Alternatives for Granada (PAG) became active in 2003, and a Midcoast Park and Recreation Task Force involving the County recommended developing the strip with informal turf areas, a rest room, and miscellaneous improvements, estimating that it would cost $850,000. However, the Harbor District (which still owned it) continued to propose various schemes, including building a fire station and residential housing.

A third group, Citizens for the Preservation of El Granada (CPEG), led by Leonard Woren, was successful at defeating a proposal to construct a large view-blocking project with a hotel, restaurant, retail space, and an RV lot across Highway 1 from the Strip. In 1996 and 2000, residents acting through CPEG derailed more development proposals, including a plan to commercially develop the Strip with a three-story building at the foot of Avenue Portola.

In 2006 there was a big victory, as the Board of Supervisors voted to rezone the Strip as the “El Granda Gateway” to preclude additional residential development.

In 2007 the Midcoast Parks Action Plan, in a comment that predicted the struggles that would continue over the next decade plus, stated “There is significant community interest in the community use of the Burnham Strip to provide a view shed to the oceans as well as a passive park area. Ownership issues and perspectives of multiple groups make planning near term use of this area difficult.” Proposals to relocate Highway One through the middle of the Strip were proposed and defeated in 2010.

Finally, the Strip Will Become a Park

Finally, the Strip Will Become a Park – Although the property was no longer zoned for commercial use, the developers were still interested. Finally, in 2010 the Granada Sanitary District purchased a six-acre parcel on the Strip at the foot of Avenue Portola from the Harbor District for $800,000. First, an underground wet-weather storage project was built in 2012 to provide resiliency for the sewer system. Then the property was restored to grassland, with only a few manhole covers showing where tanks were located under the ground.

Over the next years surfers and beachgoers continued using part of the property for parking. Skateboarders constructed a ramp on the Strip, on CalTrans land on the oceanward edge of the property. On the southwestern end of the Strip, a willow wetland with a few scattered eucalyptus and cypress trees began to expand toward the highway. Willows also grew along the unnamed drainage traversing the property from the end of Avenue Portola to a culvert along Highway 1 that, like Burnham Creek, discharged onto Surfers’ Beach.

The same local leaders continued to work on a permanent solution, and in 2014 their efforts resulted in Measure G on the October ballot. The voters were asked to approve adding park and recreational powers to Granada Sanitary District, converting it to Granada Community Services District (GCSD). The parks projects would be funded by a portion of GCSD’s share of County property taxes, not from sewer fees. Volunteers spent months campaigning and making sure the community understood the issues, including the fact that the change could result in an increase in sewer fees. The result of their efforts was a positive vote of 60% of District voters and GSD became GCSD. In 2016 GCSD purchased an additional parcel, adjacent to the preschool.

The same local leaders continued to work on a permanent solution, and in 2014 their efforts resulted in Measure G on the October ballot. The voters were asked to approve adding park and recreational powers to Granada Sanitary District, converting it to Granada Community Services District (GCSD). The parks projects would be funded by a portion of GCSD’s share of County property taxes, not from sewer fees. Volunteers spent months campaigning and making sure the community understood the issues, including the fact that the change could result in an increase in sewer fees. The result of their efforts was a positive vote of 60% of District voters and GSD became GCSD. In 2016 GCSD purchased an additional parcel, adjacent to the preschool.

In 2018 the District began working with a local landscape design firm to present concepts for a park on the Strip to the community. This was followed by a mail survey and many additional public meetings and opportunities for public comment. The community responded enthusiastically, submitting more than 500 suggestions and comments during the process.

In 2020 the GCSD Board approved the plan that is currently being prepared for submission to the County for approval. It is divided into three sections: a “village green” to the southwest, preserving the view down Avenue Portola, an active recreation area in the center across from existing buildings, and a large area to the northeast with small picnic and exercise areas, natural landscaping, and ocean views. A mix of wide and narrow trails will run throughout the park, and at the south end a new trail will lead to the highway crossing and Coastal Trail at Coronado Avenue. The County review process will allow residents to continue to add input on the plan. When approved, the goal is to begin construction of the park in 2022.

In 2021 GCSD purchased the preschool property from the owners, with the intention of converting it to a community center. Its location in the park makes it uniquely appropriate for developing a place where the community can meet, have events, take classes, and more. The GCSD Board allowed the preschool to lease the building while planning was underway, giving the business owner time to find a new location. During that time GCSD will seek community input on the center, just as for the park. The park design will be modified to include the new property for trails, landscaping, and parking.

From the days when Indians walked along the shore, to the era of the railroad and extravagant plans for development, to today’s ambitious plans for a community-serving park, the Strip has been part of El Granada history. The Strip is El Granada’s front yard, and the park will provide a focus for this small community and a resource for its residents. The people of El Granada fought to keep it open space, and the goal of the new plan is to create something that serves the community while preserving the peace and beauty of this coastal treasure.

Barbara Dye 2022 (with help and text from Matthew Clark, Fran Pollard, and Leonard Woren; some language from this report is included in Fran Pollard’s more detailed recounting of preservation efforts SAVING EL GRANADA.)

NOTES & BIBLIOGRAPHY

Many people were involved in the struggle to preserve the Strip for future generations to enjoy. Among the leaders of this effort were Fran Pollard, Leni Schultz, and Leonard Woren. Numerous people worked to preserve the Strip; those who made major contributions were: Jim Blanchard, Matthew Clark*, Kit Dove, Len & Gael Erickson, Dan Haggerty, Gerry Laster, Ric Lohman, Barbara Mauz, Fran* & Larry Pollard, Leni Schultz*, and Leonard Woren*. Those with asterisks all contributed to this history, by reviewing, correcting facts and sequences of events, providing new information, and sharing documents. I thank them for their efforts and help; they are not responsible in any way for an errors I may have made. I also want to thank Barbara VanderWerf for her wonderful book, Granada, a Synonym for Paradise, which was the most important source for this effort. I also need to state again that any mistakes in this account are my own responsibility.

Unless otherwise credited, all the photographs are reproduced from VanderWerf’s book with the permission of the author.

Clark, Matthew. 2021. Personal communication, information and text related to the Native American presence in the area and preservation efforts.

Coastsider.com. GSD closes deal for Burnham Strip property. Posted by Barry Parr, April 28, 2010

Encyclopedia of Chicago. Architecture: The City Beautiful Movement. www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org

Farmer, Jared. 2013, Trees in Paradise, A California History, W.W. Norton & Co., N.Y., NY 10110.

Half Moon Bay Review, various articles: Battle Over Burnham Continues (10/25/06); Burnham Strip fire station? (12/17/03); Harbor district scheme threatens El Granada public open space (2/20/08). “Burnham Strip rezoned to allow parking” (6/1/11)

Midcoast Community Council website (the source for most of the County and local planning history), as of 3/2021, http://www.midcoastcommunitycouncil.org/

Morell, June. 1978. Half Moon Bay Memories, The Coastside’s Colorful Past, Moonbeam Press, El Granada, CA 94018; and https://halfmoonbaymemories.com/, WordPress.

Morell, June. 2007, Princeton by-the-Sea, Arcadia Publishing, San Francisco, CA.

Pollard, Fran, 2021, Saving El Granada. Personal communication and information and text related to preservation efforts.

Postel, Mitch. 2010, Historical Resource Study for Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Mateo County, San Mateo Historical Association.

VanderWerf, Barbara. 1992, Granada, A Synonym for Paradise, Gum Tree Lane Books, El Granada, CA 94018.

Wagner, Jack R. 1974. The Last Whistle [Ocean Shore Railroad], Howell-North Books, Berkeley, CA 94710

Granada Community Services District (GCSD) Meetings ~ 3rd Thursday @ 7:30pm

Watch remotely. Comments and questions by email.

Granada Community Services District (GCSD) Agendas and Zoom Links

Granada Community Services District (GCSD) PCTV Videos

The District is responsible for parks, recreation, garbage and recycling services in the unincorporated areas of El Granada, Princeton, Princeton-by-the-Sea, Clipper Ridge, and Miramar.

GCSD Regular Board Meetings are held on the third Thursday of each month at 7:30 pm in the District’s meeting room, and are normally shown on Pacific Coast TV (PCT) (Cable channel 27) at 6:00 am on Wednesday and at 11:00 am Saturday following the meeting (but check the schedule as show times can vary).

Mission Statement

To protect public health and safety, preserve our environment, and maintain fiscal soundness by providing high quality service for wastewater, solid waste collection, recycling, and serving the community’s needs for parks and recreation, through responsible operations and management.

The Granada Sanitary District was formed in 1958 under the California Sanitary District Act of 1923. In October of 2014, the District was reorganized as the Granada Community Services District under California Government Code 61000 et seq. The District is responsible for parks, recreation, garbage and recycling services in the unincorporated areas of El Granada, Princeton, Princeton-by-the-Sea, Clipper Ridge, and Miramar. The District is also responsible for the sewage collection system and disposal for approximately 2,500 residences and businesses in these same unincorporated areas as well as the northern portion of the City of Half Moon Bay. Garbage and recycling services are provided by Recology of the Coast under a franchise agreement with the Granada Community Services District.

The District office is open Monday through Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., and is located on the third floor of 504 Avenue Alhambra, El Granada. To contact the District please call (650) 726-7093. Regular board meetings are held on the third Thursday of each month at 7:30 p.m.

Board of Directors

Board members serve four year terms, and are elected on a staggered two year basis in even numbered years. Board members receive $145 per meeting as compensation for their service on the board.

Board of Directors

Matthew Clark – President

Eric Suchomel – Vice President

Barbara Dye – Director

David Seaton – Director

Nancy Marsh – Director

Board members serve four year terms, and are elected on a staggered two year basis in even numbered years. Board members receive $145 per meeting as compensation for their service on the board.

Staff

General Manager: Chuck Duffy, Dudek & Associates

Assistant General Manager: Delia Comito

Legal Counsel: William Parkin, Wittwer Parkin LLP

District Engineer: John Rayner, Kennedy/Jenks Consultants

Administrative Assistant: Nora Mayen

Sewer Authority Mid-Coastside

The Sewer Authority Mid-Coastside (SAM) is a Joint Powers Authority created by an agreement between the Granada Sanitary District, the Montara Sanitary District, and the City of Half Moon Bay in 1976. The agreement called for the creation of the Authority to build and operate a commonly owned sewer treatment plant for the benefit of all three agencies. All sewage generated by the three agencies is pumped and piped to the treatment plant for treatment and eventual disposal. For more information on SAM, please visit their website at samcleanswater.org.

Links to previous GCSD meetings’ videos.

The Granada Community Services District (GCSD), formerly the Granada Sanitary District, gained park and recreational jurisdiction on October 1, 2014, for the unincorporated areas of El Granada, Miramar and Princeton (i.e. the “GCSD Community”) by a positive vote of 60% of the voters in the District. This reorganization allows the district to provide parks and recreation services in addition to the sewer, solid waste and recycling services it currently provides to over 2,500 residences and businesses in the District as well as the northern portion of the City of Half Moon Bay. Solid waste and recycling services are provided by Recology of the Coast under a franchise agreement with GCSD.

The parks and recreation function is funded by utilizing a portion of GCSD’s share of San Mateo County property tax revenues, not from sewer charges. GCSD’s goal is to provide parks and recreation services that benefit the GCSD community, with a commitment to robust neighborhood outreach on new projects.

Granada Parks Advisory Committee (PAC) Agenda

The PAC was formed by the Granada Community Service Board to ensure community involvement in all phases of park planning, design and development. Seven voting members are appointed by the Board to serve two-year terms. Members receive no compensation – they are neighbors volunteering to support and benefit our community. The PAC makes recommendations regarding parks and recreation to the GCSD Board of Directors. PAC meetings are held at the GCSD office at least once each quarter and are open to the public and televised. The PAC meeting schedule and meeting minutes may be found here.

The PAC was formed by the Granada Community Service Board to ensure community involvement in all phases of park planning, design and development. Seven voting members are appointed by the Board to serve two-year terms. Members receive no compensation – they are neighbors volunteering to support and benefit our community. The PAC makes recommendations regarding parks and recreation to the GCSD Board of Directors. PAC meetings are held at the GCSD office at least once each quarter and are open to the public and televised. The PAC meeting schedule and meeting minutes may be found here.GCSD owns the undeveloped “Burnham Strip” property along Obispo Street between Coronado Street and Avenue Alhambra in El Granada, which may be developed as an El Granada gateway park.

Additional potential park areas are a small GCSD-owned parcel on Capistrano Road in Princeton and the road medians in El Granada. GCSD and SMC completed a Permit Agreement in February 2018 which allows the District to make improvements to the El Granada Medians. GCSD may implement landscaping, seating, and active and passive recreational improvements on these properties, following an open and transparent community outreach process and all required permit and environmental review processes.