|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. First posted as part of the Half Moon Bay Coastside History Association’s “Coastside Chronicles” February/March 2021.

“Coastside Chronicles”

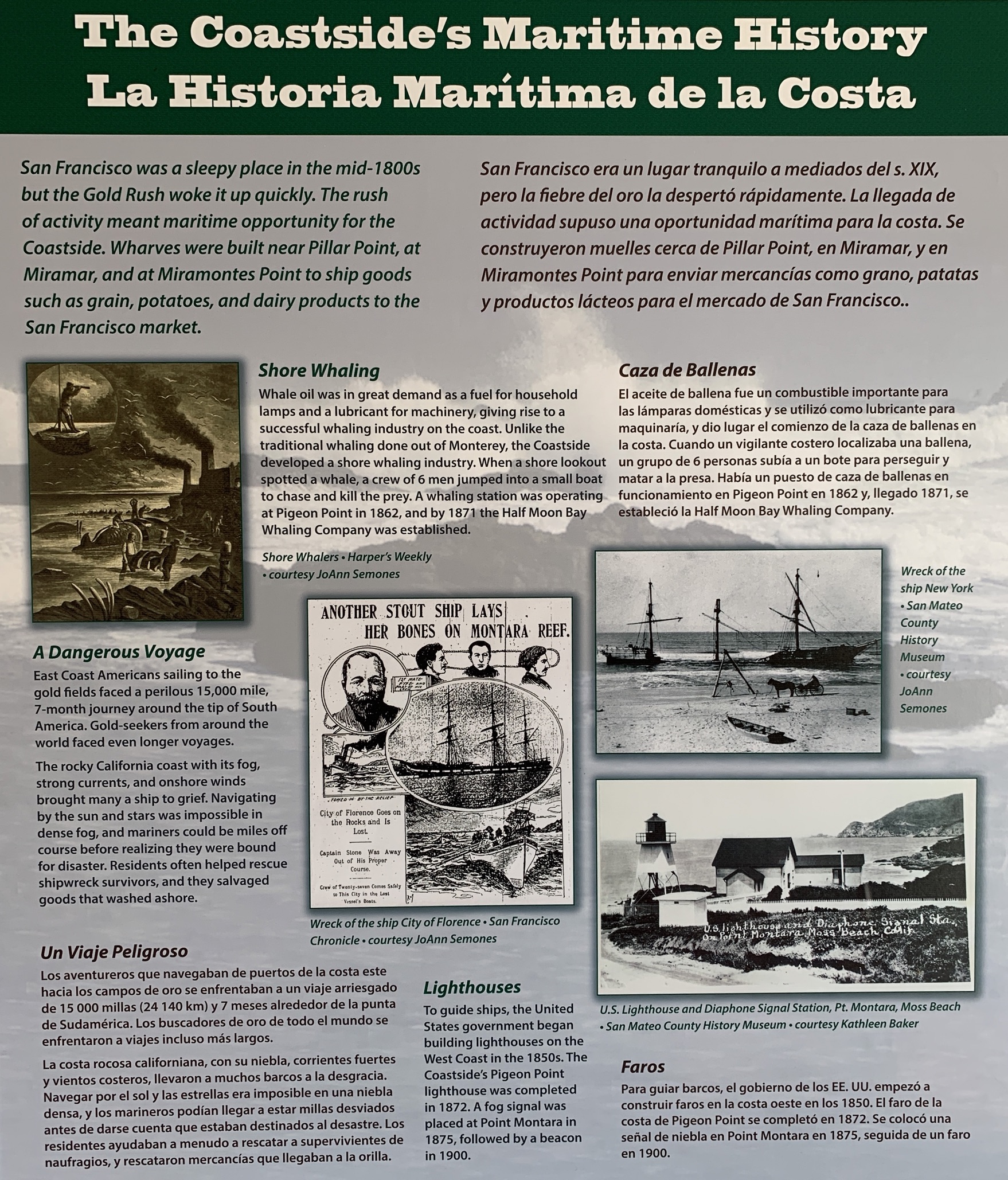

Whale-watching along the California coast is now a popular activity, so it’s difficult to imagine how the magnificent creatures were once hunted for their blubber and other parts to make oil, soap, buggy whips, corset stays, and even for use as animal feed. Even more difficult to imagine is that the whales were hunted from shore whaling stations— a risky endeavor at best. Picture six-man crews in small boats rowing out through the surf to hunt 30-to-50-ton whales, armed only with harpoons and lances.

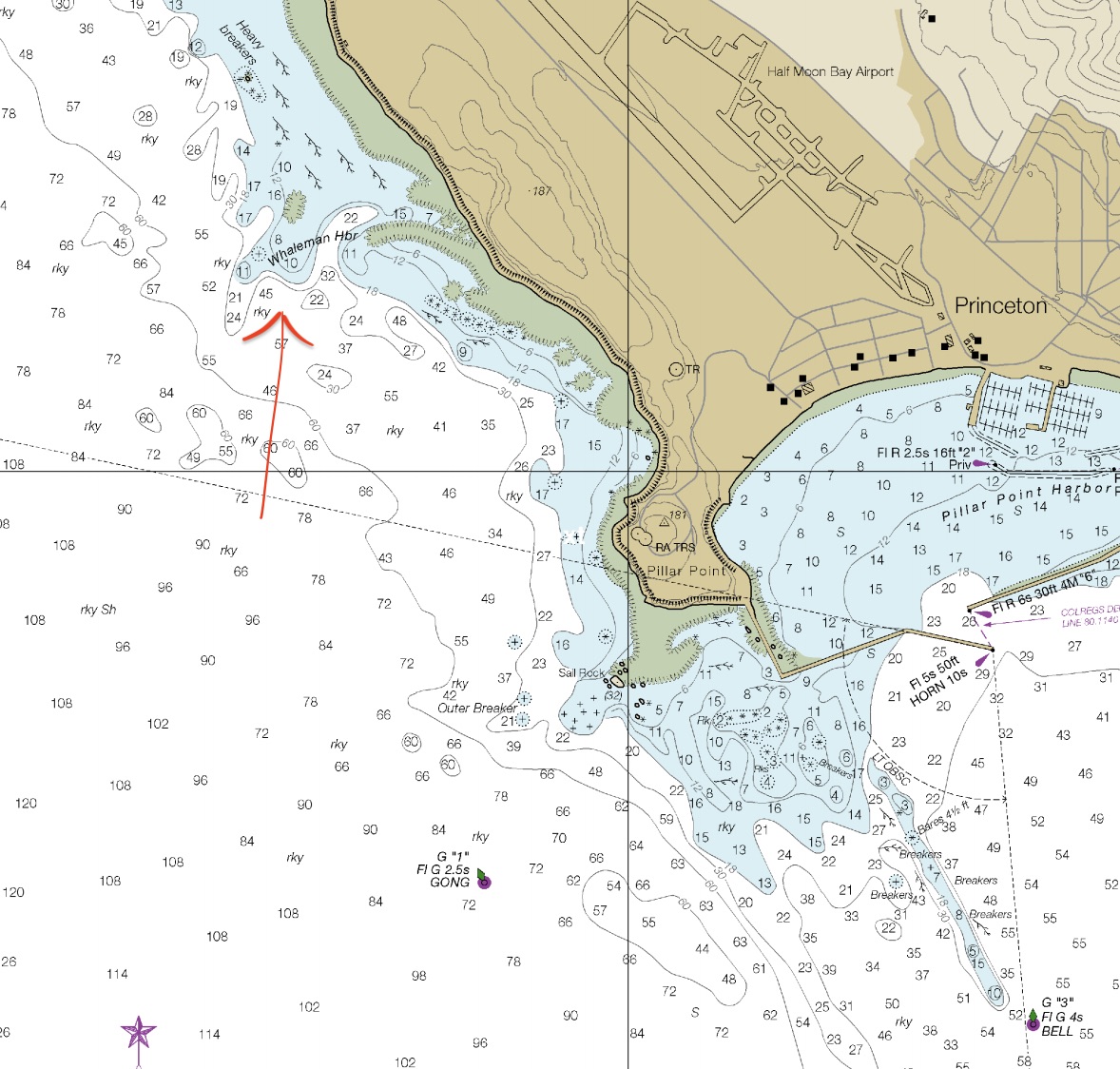

Shore whaling in California began at Monterey Bay around 1851, and was so successful that, during the latter half of the 1800s, an estimated 15 to 20 stations dotted the coast from San Diego to Crescent City, including locations at Pigeon Point and Pillar Point. It is difficult to pinpoint the actual years of operation, as accounts vary considerably. The Pillar Point station was said by one account to have started operations at Whaleman’s Harbor just north of Pillar Point in 1860, but moved to Pigeon Point a couple of years later. The operation also reportedly moved from time to time between Whaleman’s Harbor and Denniston’s Landing, a wharf that was built in 1859 by James Denniston and located in present-day Pillar Point Harbor. There was apparently whaling activity at Pillar Point, on and off for over 30 years— in the 1889 Coast and Geodetic Survey, George Davidson described the whaling station location “known as Whaleman’s Harbor…directly under the highest part of the mesa ridge just northwest of Pillar Point.”

The whalers were mostly Portuguese from the Azores who came to California during the frenzy of the gold rush, after 1848. They came to mine gold, but some became discouraged and founded whaling stations. They applied their shore whaling experience from their homeland, and also from serving on New England whaling ships. Shore whaling was similar to ship-based whaling except that it lacked a ship. The obvious benefit was not having to spend months at sea in cramped, dank conditions. But the lack of a ship also meant that whalers had to wait for the whales to come to them, further hindered by the fact that whales on the California coast are migratory, not year-round, and winter ocean conditions were too dangerous for whaling. During those months, the men engaged in chopping wood, farming, and sheep shearing, and for some, whaling was an extra source of income, not a main occupation. Even during whaling season, some whalers fished for crab, tuna, salmon, and sardines.

Whaling companies, as they were termed, consisted of a captain, mate, cooper, two boat steerers, and 11 men. Each station had two boats, each with crews of six men. Structures at a station would generally include spartan living quarters, a cooper’s shop for barrel making, a washroom, storage room, and drying room. The companies generally worked on shares or “lays,” that were similar to modern stock options. Each whaler’s shares entitled him to a portion of the proceeds from whaling, with the attendant risk of minimal or no compensation when whaling was unsuccessful. Whalers could extract as many as 30 barrels of oil from gray whales, and 50 barrels from humpback whales. The San Mateo Gazette published several reports about the whaling operations, including one in 1872 that noted that the oil brought 45 cents per gallon, allowing the whalers quite a profit. Indeed, in that era, a steak dinner could be found in many restaurants for about 20 cents.

Shore whaling was a brutal and dangerous occupation, starting with the actual hunting, and ending with the flensing or stripping of the whale and rendering to oil. The boats hunted in pairs, as it was not uncommon for a boat to be swamped or destroyed by whales, and the men would refuse to hunt unless both boats were sent out. There are reports of a terrible accident near the Pillar Point operation in 1865 that took the lives of three men when a whale swamped their boat.

The whalers rowed, or if lucky, sailed about looking for spouts. Four men remained on shore, taking turns at a lookout station with a flag. When whales were sighted from shore, the lookout would dip the flag, causing one of the two boats to turn in a circle. When the boat was headed toward the whale, the lookout would signal with the flag, and if the boat crew members were still unclear about which direction to head for the whale, they would dip the peak of the sail. The crew would stow their oars and quietly paddle when they drew close to the whale so as not to alarm or antagonize it. As we’ve noted, whales, especially those with calves, could be aggressive and dangerous.

Once the whale was harpooned it would tow the boat, usually out to sea, until it was exhausted, allowing for the second approach where it was stabbed with a long-bladed lance. If the whale didn’t sink, which was a frequent occurrence, the men would row back to shore with the whale in tow.

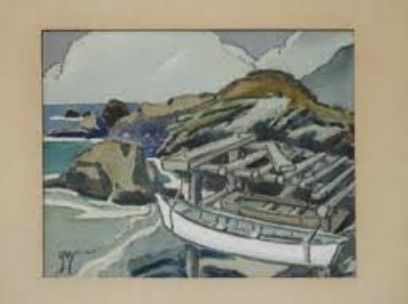

Naturalist and whaleman Charles Melville Scammon wrote, “at the point where the enormous carcass was stripped of its fat, arose the whaling station, where try-pots were set in rude furnaces, formed of rocks and clay, and capacious vats were made of planks to receive the blubber.” He goes on to describe the general chaos of the scene with the “mass of mutilated whale, together with the men shouting and heaving on the capstans, the screaming of gulls and other seafowl, mingled with the noise of the surf about the shore.”

Colonel Albert S. Evans describes the gory nature of the work at one station, stating: “…we found a party of men busy extracting the oil from heaps of blubber cut up from the huge humpback whale… They were dripping and fairly saturated with oil, and everything around was in the same condition. The stinking fluid had run down the face of the bluff to the water’s edge, and the whole place was redolent of the perfume.” The “perfume” was reportedly a stench that, mixed with the smoke of the fires would have let the entire coast know of their successful hunt.

Amazingly, while most shore whaling in California ended in the early 1900s, the last shore whaling station near San Francisco continued operation through the 1960s. The widespread availability of petroleum and other substances that substituted for whale oil, combined with scarcer and more cautious whales, and government regulation finally brought an end to whaling as an industry, and opened the doors to the magnificent spectacle of observing, rather than hunting, such fascinating creatures.

Look at the rock outcropping. Perfect spot for guiding a dead whale from deep water to a shallow area where men could butcher the carcass. Definitely not Ross’ Cove as that is sandy and deep.