|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

OWN VOICE. ~ InPerspective by Gregg Dieguez —

It feels like we’re living inside a disaster case study which will be written in a few years. “The residents of unincorporated San Mateo County knew that they shared the same risks as the Oakland Hills fire of 1991 and the Paradise fire of 2018, however…” The concern here is that the Fire Next Time[**] will be all too similar to those last two case studies. So let’s explore those risks, and what we’re not doing about them, that we should be, and what we should do now.

Footnotes: to use, click the bracketed number and then click your browser Back button to return to the text where you were reading. Images: Click to enlarge for improved readability in a new window.

Where do we stand?

What should we have learned?

What should we do now?

Where we stand – At Risk and Underprepared:

In a word what we’re not doing is: Eucalyptus. The invasive species was imported over 100 years ago in a failed attempt as a lumber crop, and poisons our soil, crowds out native species and burns like a Roman Candle. The MidCoast area of SMC is filled with those fire-vulnerable trees: along Hwy 1 north of our escape route through the Lantos Tunnel, along Hwy 92 – our escape from Half Moon Bay to the east, in the CalTrans right of way that stretches from Pacifica to Montara/Moss Beach, on the avenue medians in El Granada, and most especially throughout the 250 acres in Quarry Park.

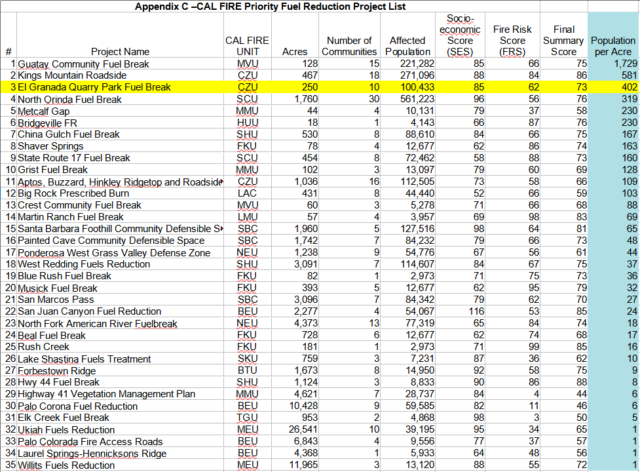

Keith Mangold has well documented the risk that those trees will incinerate our homes in the event of an El Diablo wind and a Crown Fire. And he’s not making it up. A review of the FEMA after-action report on the 1991 Oakland Hills fire, the Paradise fire, and the CZU lightening fire last year indicate that the MidCoast faces similar high wildfire risks, but with less evacuation and shelter options, and a similar lack of fuel reduction preparation. The valid concern is that a Quarry Park wildfire may be indefensible under the wrong conditions (e.g. a canopy fire). Quarry Park/eucalyptus is the ranked the 16th worst fire risk in the state by CalFire, but if you consider the density of population (as I have in the chart at right >), it ranks 3rd. But a permanent solution is not funded (see below).

What should we have learned:

Lessons NOT Learned from Paradise:

There are several parallels between our situation and the Camp Fire in Paradise… the deadliest, most destructive fire in California history, killing 86 people, destroying 12,000 homes and displacing 26,000 residents. Paradise knew enough to plan for evacuation but it wasn’t sufficient, even with five two-lane roads and one four-lane road leading out of town. MidCoast, we have one (1) two-lane road. Paradise failed to develop plans to evacuate the entire community at once and even narrowed parts of Skyway Road, from four to two lanes, to improve pedestrian safety and boost commerce. That road ‘improvement’ sure sounds a lot like our recent Connect The Coastside plan, adding bike lanes and roundabouts to roads already choked with visitors during fire season. The roads out of Paradise gridlocked within an hour of the first evacuation order.[1] “In truth, the destruction was utterly predictable, and the community’s struggles to deal with the fire were the result of lessons forgotten and warnings ignored.”[2] That sounds a lot like where we are, right now.

A state fire planning document warned in 2005 that Paradise risked an ember firestorm akin to the one that ripped through Berkeley and Oakland 14 years earlier. The “greatest risk” was an “east wind” fire, the document said, “the same type of fire that impacted the Oakland Berkeley Hills during the Oct. 20, 1991, firestorm” that killed 25 people.  A year later, the Butte County grand jury warned that the town faced disastrous consequences if it did not address the capacity limits of its roads. But Butte County supervisors and planners rejected the panel’s call for a halt to growth until the evacuation problem was met – which sounds a lot like Connect The Coastside and the Half Moon Bay LCLUP, ignoring the issue.

A year later, the Butte County grand jury warned that the town faced disastrous consequences if it did not address the capacity limits of its roads. But Butte County supervisors and planners rejected the panel’s call for a halt to growth until the evacuation problem was met – which sounds a lot like Connect The Coastside and the Half Moon Bay LCLUP, ignoring the issue.

Flaws in such planning are so common that FEMA’s staff describes them as the “deadly sins” of emergency management: Practicing drills that guarantee success; assuming that plans can be scaled up when a massive disaster strikes; relying on government systems to work under pressure; failing to plan how to protect vulnerable populations, such as the elderly; and mistrusting the public, which often leads to not warning the public early enough.[2]

– former FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate

And of course, here on the Mid-Coast we have intermittent cell service, poor internet bandwidth, and PG&E service so fragile it is intentionally shut down in high winds.[3] And let us not forget that it was a PG&E spark that started the Paradise fire. El Granada residents report dozens of aging utility poles and power lines crossing their roads amidst the eucalyptus groves. PG&E might not just start the fire, it might also prevent the warning systems from working, as has happened elsewhere. [4]

Lessons NOT learned from the 1991 Oakland Hills Fire:

Again, the situation in Quarry Park parallels several of the risk factors cited in the FEMA report: “Extreme fire risk created by five year drought, low humidity, and Diablo winds; highly combustible natural fuels, inadequate separation between natural fuels and structures; steep terrain, homes overhanging hillsides, narrow roads, limited access, limited water supply.” Here are some of the lessons FEMA and Oakland learned the hard way:

- Inadequate access roadways for emergency vehicles and exit roadways for residents.

- Water storage and distribution systems inadequate for fire protection purposes.

- It is not feasible to provide a fire suppression organization to master the situation that occurred in Oakland.

- Residential internal automatic sprinkler systems alone would not provide protection against this type of fire exposure.

- Communications systems that are adequate for normal times and situations may be easily overwhelmed in a disaster situation.

- It is extremely difficult to evacuate a heavily populated interface zone…. Once a fire starts spreading through the area, it may be too late to evacuate.[5]

- It is not clear that even an early series of aerial attacks could have controlled this fire (because of smoke and fire thermals).

- Existing expectations for “jump potential” may need to be reevaluated…. The conditions for a long “jump” were perfect and the fire spread rapidly into an entirely new area.

- It may have been feasible to protect some of the structures with exterior sprinkler systems, if adequate water flows and pressures had been available and the more severe exposures to wildland fuels had been reduced.

- Compressed Air-Foam Systems (CAFS) appear to be very useful in applying a thick foamy covering to protect severely exposed structures.

First, get rid of the fuel for the fire. Second, expand the evacuation capacity and/or reduce the population density. Let’s start with the easy stuff. Eucalyptus is the worst tinder possible, yet San Mateo County has a tree-cutting permit ordinance which charges residents for removing these trees and slows the process markedly. It has been over ten (10) years since residents first requested eucalyptus be exempted from this permitting process, and we are still waiting. IMMEDIATELY remove all barriers to resident removal of eucalyptus; in fact, INCENTIVIZE residents for removing these trees. Include the eucalyptus on the medians in El Granada in this removal program. The County delay in changing this ordinance is a deadly risk.

The good news is: this problem has been solved before. In San Diego, they completed a eucalyptus removal and wildlife habitat improvement effort over the course of 12 years, finishing in 2015. It was expensive, so they began with a parcel tax which attracted leveraged funding from other state and federal agencies. Currently, we are 18 years behind San Diego, and we haven’t even started.

Which is not to say County Parks has done nothing regarding fuel reduction in Quarry Park. They undertook a ground cover thinning program in 2019. In spite of this, residents report that not a single mature eucalyptus tree has been removed to date.[6] In 2021 Parks is planning on starting 3 Quarry Park fire prevention projects in their current 5 year plan, including a fuel break[7]. Together, those 3 upcoming projects total $1.2 million… over 5 years. The ballpark estimate to remove eucalyptus and replant Quarry Park with native species is $60 million. Thus, the County Parks’ plan is Zero for removal and replanting, and only 0.4% annually of the budget required to properly rebuild Quarry Park. Note that the CZU lightening fire cost $68 million just to fight[8], and the properties at risk near Quarry Park are worth Billions, so $60 million seems a prudent “ounce of prevention”. In addition, “What Happens In El Granada Might Not STAY In El Granada.” The coast is at wildfire risk from Pacifica through Half Moon Bay.

And none of those under-funded Parks plans address the fuel risk areas we listed at the top of the article which are outside of County Parks’ jurisdiction….

Get Involved!

The MCC is holding a meeting 7pm on April 14th which will involve several county agencies and actors, like Parks, CalFire, and Supervisor Don Horsley. We need residents to attend that meeting. So many residents should attend that you will not have time to speak, but your presence will punctuate the importance of this issue. We need to get Parks some help. Money for certain. And probably expertise from CalFire and/or the RCD – which is known for its expertise in both fire prevention projects and in leveraging local funding into sizable grants – funds sufficient to address our eucalyptus problem.

By a fortunate coincidence, the San Mateo County Local Hazard Mitigation Plan (LHMP) is being updated this year after 5 years. As a result of our efforts last week, I believe all eligible MidCoast agencies are now partners in this planning effort. The LHMP may be a major funding vehicle for several disaster preparedness and resiliency initiatives – including fire, flood, earthquake, etc. We (residents and the MCC) need to participate in that LHMP planning effort (take survey HERE) and motivate all local agencies to do so as well. There is a May 21st deadline for agencies to submit their initial plans. Here are some steps to get things rolling…

First, residents should demand that the MCC represent our voices in disaster preparedness (midcoastcommunitycouncil@gmail.com). Perhaps this could involve the creation of an adjunct group of local residents with expertise and interest, which several have expressed to me. Second, demand a plan – including funding – for a permanent solution to wildfire risk in Quarry Park. Third, participate in creating a disaster preparedness issues list for the LHMP by the end of April, including evacuation, shelter, communications and other priorities. Fourth, get the County and MCC to identify the agencies responsible for each disaster-related issue, and demand that those agencies include in their May 21st LHMP submissions solutions to those issues. Fifth, have the MCC and involved residents Watch What They’re Doing (and Not Doing).[9]

Down the road there are other levers we might need to pull: county and community parcel taxes for grant seed money, ballot measures, lawsuits[10], tax boycotts, petitions, protest campaigns, recall elections, and [your ideas here]….?? more???

How will we know when we’re done? When the CalFire risk map no longer shows Quarry Park or other eucalyptus areas in the Mid-Coast as wildfire hazards.

FOOTNOTES:

[**] The Fire Next Time:

With a tip of the hat (and apology?) to James Baldwin, whose words remain relevant today: “A national bestseller when it first appeared in 1963, The Fire Next Time galvanized the nation, gave passionate voice to the emerging civil rights movement—and still lights the way to understanding race in America today.”

[1] Gridlock:

Paradise was divided into 14 zones for orderly evacuations. Skyway Road, one of the major routes leading to nearby Chico, was designated for “contra-flow,” meaning authorities could turn the road into a one-way evacuation route. “As good as all the planning was, it was totally overwhelmed by the events of Nov. 8,” Paradise Mayor Jody Jones said during Tuesday’s meeting of transportation commissions from Washington, Oregon and California… https://www.govtech.com/em/preparedness/Grim-Lessons-Learned-and-Warnings-from-California-Fire-Stories-.html

[2] Utterly Predictable: and FEMA staff comments:

https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-camp-fire-deathtrap-20181230-story.html

[3] Power outages at same time as fire:

“Power outages that occurred simultaneously, as the CZU Complex fire was spreading, also made outreach efforts more difficult, Larkin said.”

https://www.santacruzsentinel.com/2021/03/15/68-million-price-tag-to-fight-czu-lightning-complex-fire/amp/

[4] Failed Warning Systems:

But interviews and records released by the city and county show the emergency warning system failed on many levels. Only a fraction of Paradise residents were signed up for the service — city officials at first estimated there was no better than 30% enrollment, then later told The Times they did not have access to the subscription list. Many of the emergency alerts failed to go through — CodeRed logs showed initial call failure rates of 40%, climbing to 60% as the fire progressed. Many subscribers told The Times they never received calls. He now favors a siren system that could warn everyone at once. https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-camp-fire-deathtrap-20181230-story.html

[5] Rate of Wildfire Spread:

Racing flames: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2018/11/09/california-wildfires-why-have-flames-spread-so-quickly/1941342002/

“The flames from the Camp Fire in Butte County, California, were spreading at 80 acres per minute Thursday, which is equivalent to burning an entire football field every second, according to UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain. ”

[6] No trees removed: El Granada resident comment: “Since Quarry Park was listed #16 on the CAL FIRE Priority list in Feb, 2019 not a single mature eucalyptus has been removed from Quarry Park. Projects that have been performed could be described as trail or park improvements and have certainly not made me feel any safer.”

[7] Fire vs. Fuel Breaks

The concept behind fuel breaks is to create a corridor that facilitates firefighter movement during a wildfire. A fuel break is a strip of land that is purposely converted from one vegetation type to another for firefighting purposes. In our region, fuel breaks are typically long strips of land that are converted from native chaparral to non-native and invasive grasses and weeds. They can be up to 300 feet wide. Fuel breaks are often confused with fire breaks and fire lines, which are constructed differently and used for different purposes. A fire line is typically 10 feet wide or less and is almost always built during wildfire suppression. Fire breaks are a strip of land 20-30 feet wide where vegetation has also been removed down to bare soil. Like fire lines, fire breaks are usually created under emergency conditions during wildfire suppression with the intention of acting as barriers to further wildfire spread. They are typically created with a bulldozer and are thus sometimes called “dozer lines.” A strong criticism of the fuel break approach to fire control is that the headlong rush of a large fire can carry it across a wide break – manned or not – under extreme conditions. https://lpfw.org/fire/fuel-breaks/

[8] Cost of Fire Fighting:

The CZU lightening fire cost $68 million to fight, and the full bill for erosion control and later damage is not included in that amount. Santa Barbara County debris flows killed 20 people who did not evacuate in January 2018 when Montecito — scarred by the Thomas Fire of 2017 — experienced mud and boulders rush down into its creeks and valleys at 20 mph, and nature thrown down from the Santa Ynez Mountains. https://www.santacruzsentinel.com/2020/12/13/lessons-learned-how-the-countys-emergency-services-personnel-are-planning-through-multiple-disasters/

[9] Lack of Wildfire Prevention Progress:

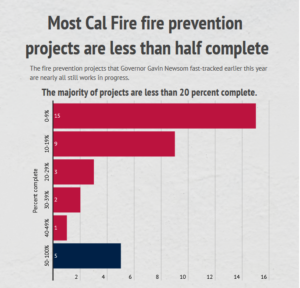

Nearly All The Fire Prevention Projects Fast-Tracked By Gov. Gavin Newsom Are Less Than Half Complete. https://infogram.com/calfire-projects-1h1749j0wnkx6zj

[10] Legal Liability: El Granada resident comment: “Where trees on unimproved County road easement property may pose a fire or fall threat to an existing home(s) (perhaps within 100′), the County’s position may not provide adequate cover from liability exposure should reasonable evidence show a lack of maintenance response on their part contributed to any significant private property loss or loss of life.”

More From Gregg Dieguez ~ InPerspective

Mr. Dieguez is a native San Franciscan, longtime San Mateo County resident, and semi-retired entrepreneur who causes occasional controversy on the Coastside. He is a member of the MCC, but his opinions here are his own, and not those of the Council. In 2003 he co-founded MIT’s Clean Tech Program here in NorCal, which became MIT’s largest alumni speaker program. He lives in Montara. He loves a productive dialog in search of shared understanding.

https://fire.ca.gov/media/5584/45-day-report-final.pdf

Very good and well-documented article. With the historic fire seasons of recent years in California, will coastsiders finally stop pooh-poohing the dramatic, widespread, existing and potential negative consequences of the large and spreading stands of invasive trees in our area? One can hope, but it’s hard to be sanguine.

A few notes:

The concentration on the major problems of Quarry Park/El Granada overlooks large and spreading concentrations of eucs and a couple of non-native (to our area) gymnosperm species elsewhere on the Midcoast and in HMB. All major fire hazards should be addressed simultaneously. Areas of overdeveloped Moss Beach and Montara are as much at risk as El Granada

No mention is made of Monterey pines and Monterey cypresses, which also constitute a major wind-driven fire threat in our communities. The pines are particularly flammable. Neither of these species should require a permit for removal.

Many acres of eucalyptus have been clearcut and chipped in place in Wunderlich County Park, so County Parks has some familiarity with their removal. Several hiking trails go through these areas, so it is easy to access them to see what was done and what remains.

The MidCoast isn’t Paradise: the primary two-lane evacuation rout out of Paradise wasn’t lined with Eucalyptus forest on both sides as it is on the MidCoast.