|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

HMB HISTORY ASSOC. ARTICLE. Thanks Ellen Chiri-Bakaleinikoff.

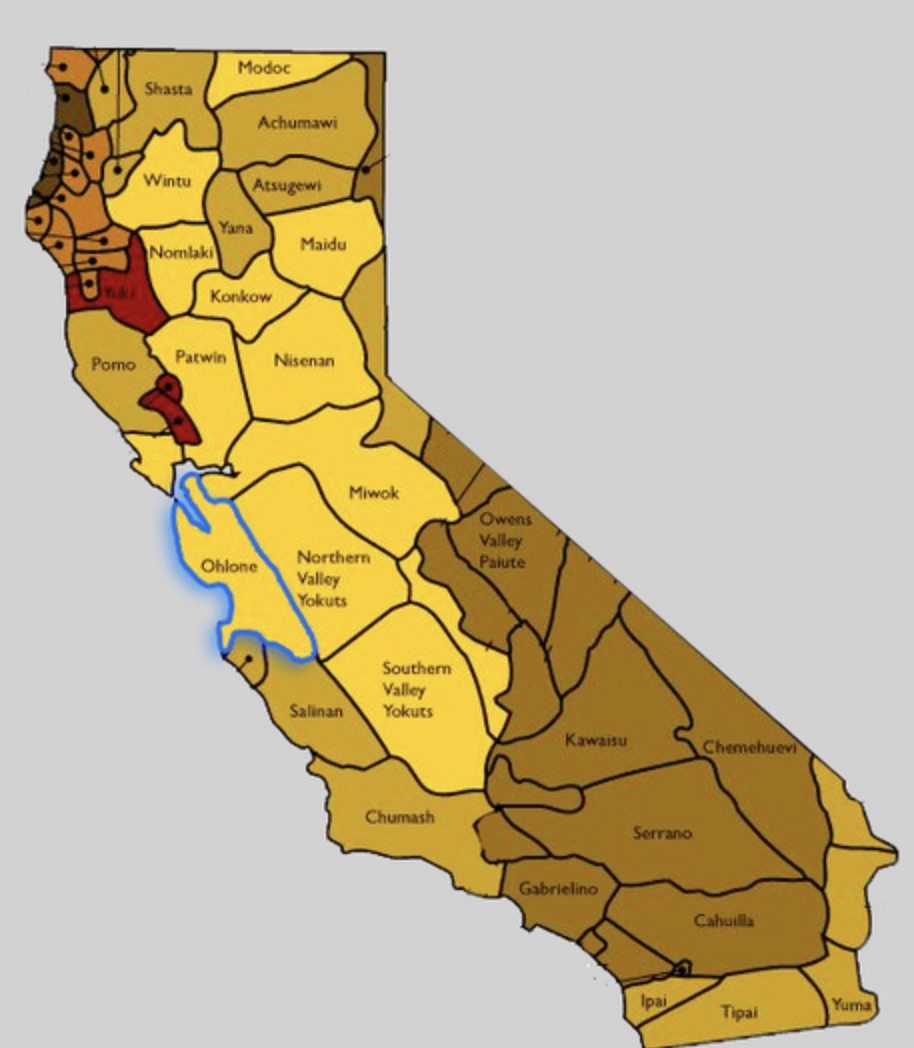

Ohlone—The First Coastsiders

The first people on this fertile coastal terrace believed that they came from the earth. In their first 14,000 years here, they developed a way of life that was centered on caring for the land.

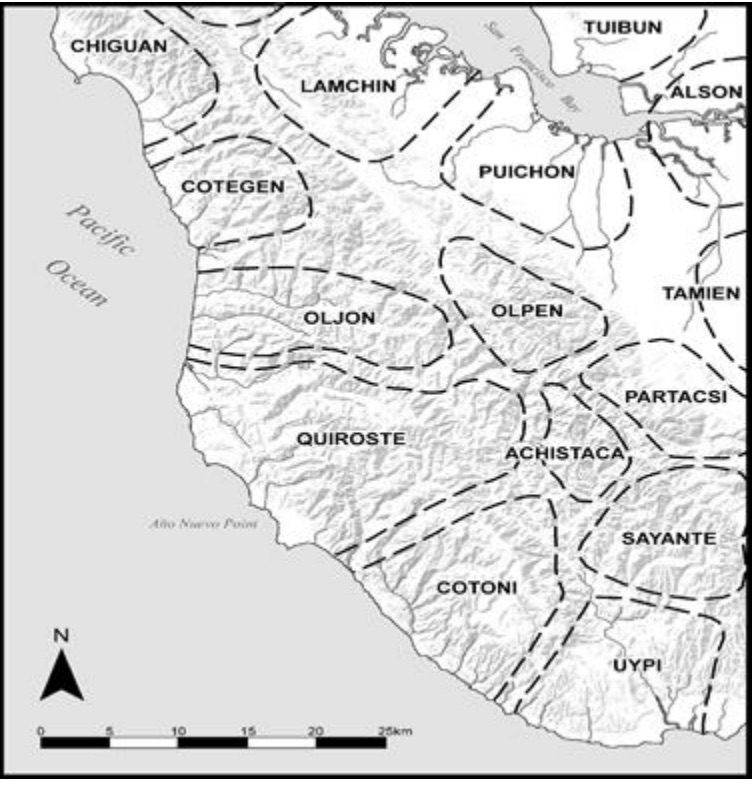

The people now referred to collectively as, Ohlone, were organized into at least 50 politically autonomous tribal groups that spoke several dialects. Extended clans formed villages, each of which included societal organizations.

Working together, the organizations directed storage of surplus food, constructed buildings, planned hunting strategies, and determined when and where to relocate to follow the seasons.

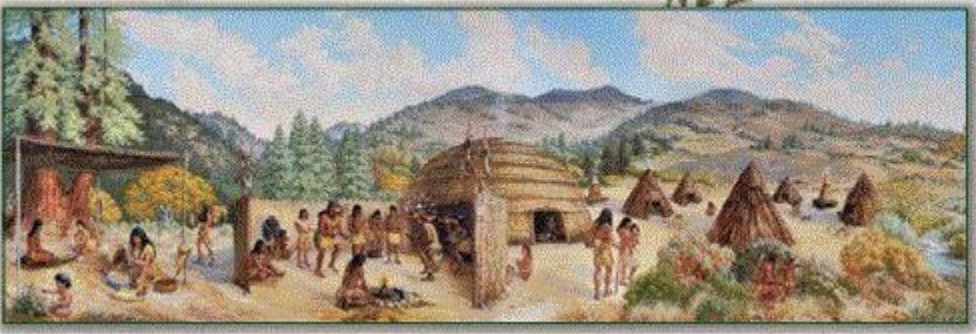

Houses called “ruk” were built of tightly thatched tule reeds woven over a frame of willow poles. Each house had an indoor and an outdoor hearth, and an underground oven for roasting bulbs, shellfish, and meats.

The Ohlone hunted small land animals and communally hunted large animals like elk and deer. They caught salmon and trout from streams, caught surf fish from the ocean, and gathered shellfish such as mussels and clams. Women were adept at deep dives for abalone—the meat was eaten; the shells were used as utensils or decoration, and were an important trade item.

The Ohlone traded with tribes all over California and as far east as Colorado, trading abalone shells, olivella shells, and other local items for things not available here, such as obsidian for arrow- and spearheads. The Ohlone diet was primarily plant-based and included grass and plant seeds, berries, mushrooms, shoots, bulbs, seaweed, fresh greens, and acorn meal. Seed-producing grasslands were once a dominant feature of the coastal terrace, and the Ohlone milled flour from the seeds of plants like clarkia and tarweed.

Many plants used medicinally by the Ohlone are used in today’s medications. For example, the bark of the willow contains salicylic acid and was chewed or used as a tea to relieve minor pain; salicylic acid is the main ingredient in aspirin. Another example is coastal gumplant (grindelia), whose sticky buds were used for respiratory, skin, and digestive ailments; today it is the main ingredient in Tecnu, a skin product for relief of poison oak rash.

Native peoples throughout California managed the landscape using fire to increase seed production. After the grasslands were burned in late summer, new vegetal growth not only produced new food crops, but also attracted game for hunting. When Europeans came to California, they described areas as tended gardens rich in wildflowers, edible bulbs, and carefully groomed grasslands. They didn’t come upon a wilderness—they came upon a managed landscape.

The Ohlone cleared the lands around their seasonal villages not only by burning, but also by intense and constant tending, using gardening activities familiar to us today–weeding, shrub and tree removal, pruning, planting, and plant propagation. This encouraged herds of deer and elk to gather in clearings where they–and the people–could see predators like bears, mountain lions and wolves. This mural, on display at the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History, shows daily activities in an Ohlone village.

For the mural, artist Ann Thiermann invited a group of Quiroste to stage scenes in the most representative way possible. Among the activities shown are a woman grinding acorns, people playing a game, dancers performing a ceremonial dance, and a man teaching a boy to hunt. The large round building is a hall where meetings and ceremonies took place.

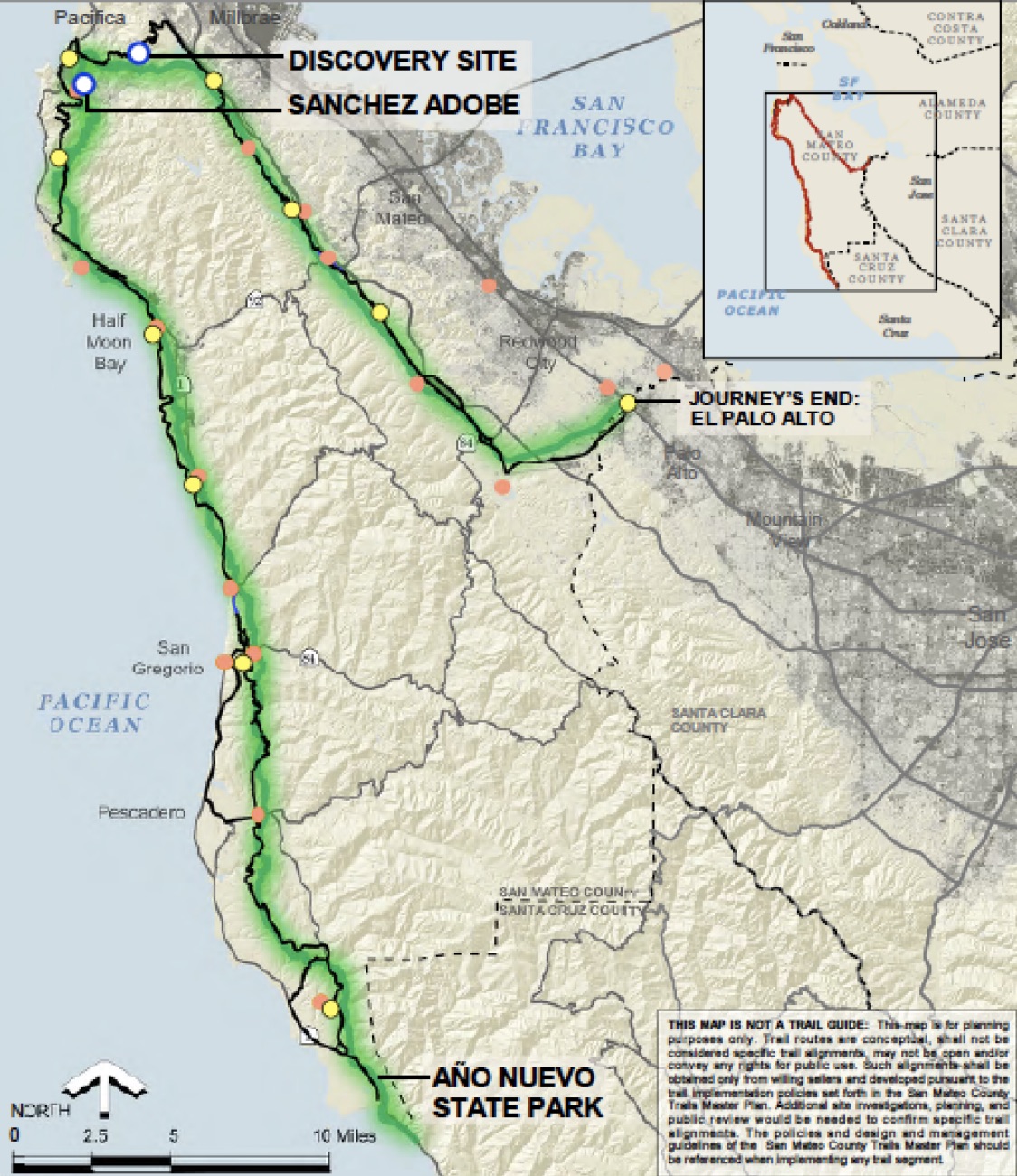

The mural depicts the Quiroste village near Año Nuevo that is believed to be where the 1769 Portolá expedition was welcomed, and where the men were cured of scurvy. As the expedition continued to travel the Coastside they were welcomed, fed, and cared for at each village.

The Coastside’s increasing populations of Spanish colonists, Mexican rancheros, and American settlers changed the Ohlone way of life forever. Foreign cattle, horses, and sheep grazed on the native plants, drastically reducing the native people’s food supply. Foreign plants such as wild oats, mustard, radish, and bur clover were introduced, further degrading the food supply and increasing the Ohlone’s dependence on the foreigners for sustenance. In 1850, California statehood followed the Gold Rush and led to institutional racism and servitude. Many Ohlone survived by blending into Latino communities, having been given Spanish names and culture; some small bands escaped to live, hidden, in the forests.

Today the Amah Mutsun are collaborating in Quiroste Valley with archaeologists from California State Parks and the University of California to research and re-introduce the traditional resource and environmental management that was practiced before the arrival of Europeans. The small valley was a seasonal home of the Quiroste and their predecessors for millennia.

Descendants of the first people still live on the Coastside, and continue to identify themselves as the Ohlone people—they are our neighbors, our co-workers, our classmates, our friends. Visit our Programs page to see video presentations of Ohlone lifeways on the Coastside by Mark Hylkema, Santa Cruz District Archaeologist and Tribal Liaison for California State Parks.