|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. From the Half Moon Bay History Association’s Coastside Chronicles, January 2023, by —Marc Strohlein.

Many Coastside residents know Rancho Corral de Tierra as a scenic part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and a great place for hiking, with many scenic views. Yet the former rancho has a rich history, including that of the original land-grant owner and important figure in Coastside history named Francisco Guerrero y Palomares.

The original residents of the area were the Ohlone Chiguan people, who lived in the area for several thousand years before the arrival of Spanish explorers in 1769. The area was colonized by Spanish soldiers and missionaries who established the Missión San Francisco de Asís in 1776, now more commonly known as Mission Delores. The missionaries attempted to convert the Ohlone to Christianity, ultimately resulting in the decimation of the Indigenous population from disease and poor treatment.

By the 1790s, Franciscans were grazing cattle in the Rancho Corral de Tierra area. The land was ideal for pasture because the original Ohlone inhabitants had periodically burned the land, leaving grass that was perfect for the longhorn cattle. The Spanish had earlier observed that the ridge and coastline around present Half Moon Bay has a similar shape to a natural earthen corral, which led to the name Rancho Corral de Tierra.

The Mexican War of Independence ended Spanish control in 1821, and by 1833 the Mexican Congress began seizing Church lands, starting the process of secularization of mission land and property. The original intent was purportedly to return land to the Ohlone, but most was instead granted to soldiers and friends of government officials, including Francisco Guerrero y Palomares.

It’s important to note that the Spanish naming convention puts the mother’s last name after the father’s, so Guerrero is the last name for this ranchero. Also note that Californians of this era were Mexican citizens also known as Californios.

Guerrero was born in Tepic, Mexico in 1811 and traveled to California in 1834, soon attaining the title of juez de paz, or justice of peace, for the lands around San Francisco. That duty included assisting with secularization of mission property. His efforts led to his promotion to the post of Alcalde of Yerba Buena, a mayoral position in what became San Francisco.

Historian Zoeth Skinner Eldredge wrote: “Guerrero was a man of high standing and well regarded by Americans as well as Californians.” Merchant and trader William Heath Davis, in his book Sixty Years in California, wrote that he found Guerrero to be “one of the most important men in the district” and noted that he was appointed sub-prefect, an official charged with the administration of a territory.

Guerrero married Josefa de Haro, the daughter of an Alcalde. They had ten children, but only two males lived to adulthood. Guerrero applied for the land grant for Corral de Tierra in December of 1838, based on his military record and submission of a diseño, a basic map of the property he desired.

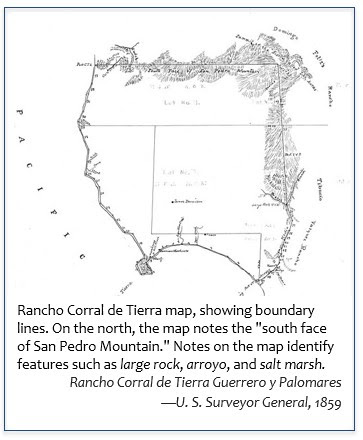

In 1839 Guerrero was granted his 7,766-acre rancho by Governor Pro-Tem Manuel Jimeno Casarín. The grant stretched from Montara Mountain to the north, the ocean to the west, Arroyo de en Medio (Medio Creek) to the south, and the first mountain ridge to the east. It included today’s communities of Montara, Moss Beach, Princeton, and El Granada. The southern portion of Rancho Corral de Tierra was granted to Tiburcio Vasquez, extending from Medio Creek to Pilarcitos Creek.

In 1839 Guerrero was granted his 7,766-acre rancho by Governor Pro-Tem Manuel Jimeno Casarín. The grant stretched from Montara Mountain to the north, the ocean to the west, Arroyo de en Medio (Medio Creek) to the south, and the first mountain ridge to the east. It included today’s communities of Montara, Moss Beach, Princeton, and El Granada. The southern portion of Rancho Corral de Tierra was granted to Tiburcio Vasquez, extending from Medio Creek to Pilarcitos Creek.

Historian Frank M. Stanger noted in his book South From San Francisco “There were, in fact, strings attached to make sure that this would be a homestead, and not merely a speculation. The land must not be sold, mortgaged, or entailed; trees must be planted, and within one year a house must be built and it must be inhabited.” Guerrero made good on all but the latter condition as he largely resided in Yerba Buena, not at his rancho. He did have an adobe house built at the rancho at the foot of the hills at Guerrero, near present-day Princeton, where he and Josefa would stay during their visits.

Guerrero lived primarily in Yerba Buena because he had significant official positions and duties in the city. Moreover, access to the ranchos was difficult due to poor roads and steep hills. Mitchell P. Postel noted in his book Peninsula Portrait that the ranchos were “largely cut off from the rest of Mexico’s territories,” and that “under such primitive conditions, rancheros were left to their own devices to govern their affairs.” Guerrero took advantage of his presence in Yerba Buena to meet trading partners, and Davis said that Guerrero was “very social in his nature and fond of little dances which were frequently held at his house.”

Life for rancheros such as Guerrero was described by Stanger as “free and easy,” as the cattle, identifiable by their brands, “ranged freely with little or no watching, and there were servants to do the drudgery.” Indigenous Ohlone from the mission outposts were, in Postel’s words “Kept as laborers in a feudal arrangement. A few of the most favored were allowed to become vaqueros,” and were America’s first true cowboys.

Each spring vaqueros rounded up calves for branding and steers for slaughter at the matanza, and held rodeos. Those events were major days-long festivals, with the vaqueros participating in riding competitions, bull fights, and grizzly bear hunting, with Guerrero and wife Josefa presiding over the events. Postel noted, the rancheros were “rich in land and cattle but essentially lived a cash poor existence.” Hides and tallow from cattle were used much like currency and by 1840, California rancheros were trading between 50,000 to 80,000 hides to 20 to 30 foreign merchant ships each year.

As more and more Americans arrived in the region, Guerrero found his ability to serve his sub-prefect role was difficult as he had no staff and Yerba Buena was entering a notoriously chaotic and dangerous period.

Despite his challenges in the increasing lawlessness of the region, Guerrero was accommodating to American immigrants. Davis said that Guerrero “encouraged immigration of foreigners to California” and at times, “defended their rights.” Despite his love for his native country, he believed that California needed, in Heath’s words, to “pass from control of Mexico.” Heath also noted that Guerrero had no dislike for Americans and “admired them as a progressive people and saw that they would ultimately control.”

On July 9, 1846, the Bear Flag Revolt ended with the Americans taking possession of Yerba Buena. It was that revolt and the accompanying tensions and the ensuing war between the United States and Mexico that convinced Guerrero and his family to leave Yerba Buena and take up permanent residence on their rancho. When the situation became calmer, he returned to the city and served as an elections inspector.

Guerrero’s considerable knowledge of legal issues surrounding ownership of the rancho properties coupled with his sympathetic relationship with Americans made him extremely valuable. Many of the new immigrants had scant respect for the Californios and their property rights, and Guerrero was called on to testify on the validity of many claims.

Guerrero’s expertise that made him so valuable to Americans ironically may have led to his demise. Both he and Tiburcio Vasquez were prosecution witnesses in the land-fraud case involving Prudencio Santillan, a priest, and both Guerrero and Vasquez were murdered. In 1851 a Frenchman on horseback reportedly struck Guerrero on the head with a slingshot and Heath wrote that he believed that “parties interested in the Santillan land claim were instigators of the murder.” Vasquez was murdered in Half Moon Bay in 1863.

Davis described Guerrero as one of the “few real founders of San Francisco,” and one testament to that importance is the naming of Guerrero Street in San Francisco for him. With the cession of California to the United States following the Mexican American War, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided that the land grants would be honored, and the grant was finally patented to the widow Josefa de Haro de Guerrero in 1866. She had married American James Denniston in 1853, making him the first American owner of the rancho.

Today, much of the former land grant is now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and few if any signs of the ranchero years remain, but it is interesting to think back to the days of rancheros, vaqueros, rodeos, and grizzly bears in that not-too-distant past.