|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. From the Half Moon Bay History Association’s Coastside Chronicles for Autumn 2023. Indigenous Fishing: Coastal Waters Provided Food, Tools, and Money —Ellen Chiri.

The coast of San Mateo County extends from Pacifica in the north to Año Nuevo in the south. The first people to inhabit this land, now referred to collectively as Ohlone by contemporary scholars and some descendants, were organized into at least 50 politically autonomous tribal groups. Societal organizations within the tribal groups worked together to direct communal activities that included fishing. In addition to the bounty of food, the ocean provided material for making tools, for personal adornment, and for trade. For example, abalone was used to make fishhooks as well as pendants and badges that identified organizations. Olivella-shell money was used all over California, so coastal people provided the medium of exchange for a large economy.

As archaeologist Mark Hylkema said in his 2022 History Association presentation Ancestral Native American Lifeways of the Half Moon Bay Area, the Quiroste people of the Año Nuevo area were “sitting on the bank” because of the wealth of olivella shells there.

William H. Brewer was a member of the 1860 California Geological Survey. In his journal, published as Up and Down California in 1860-1864, he wrote about the coast: “…rocks jutting into the sea, teeming with life… Shellfish of innumerable forms, from the great and brilliant abalone to the smallest limpet… millions of them. Crustaceans…of strange forms and brilliant colors, scampered into every nook at our approach…Every pool of water left in the rugged rocks by the receding tide was the most populous aquarium to be imagined…” The people gathered seaweed from the rocks to be eaten fresh or dried; seaweed was also used to wrap seafood, keeping it cool and preventing spoilage. Shellfish such as mussels were gathered from the rocks; clams were dug from the sand. Abalone was gathered from the rocks, or by women who were adept at deep dives.

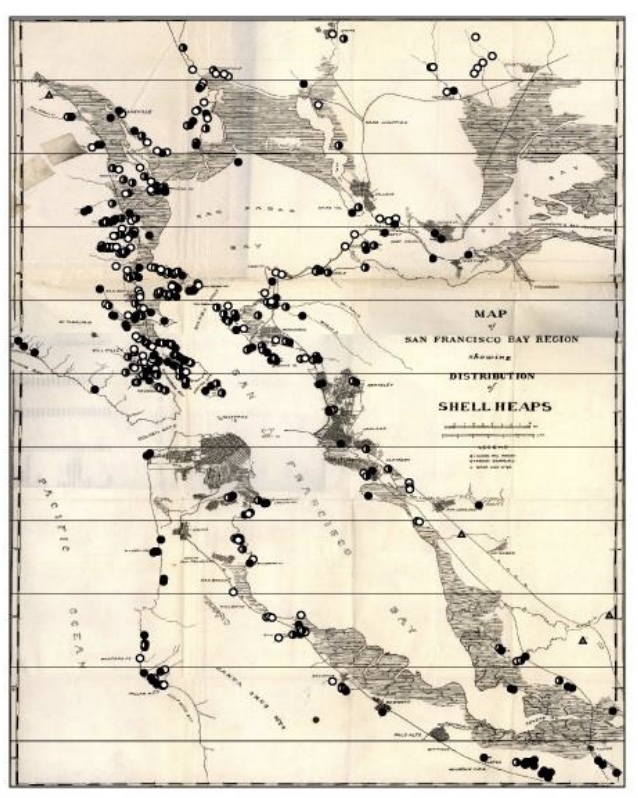

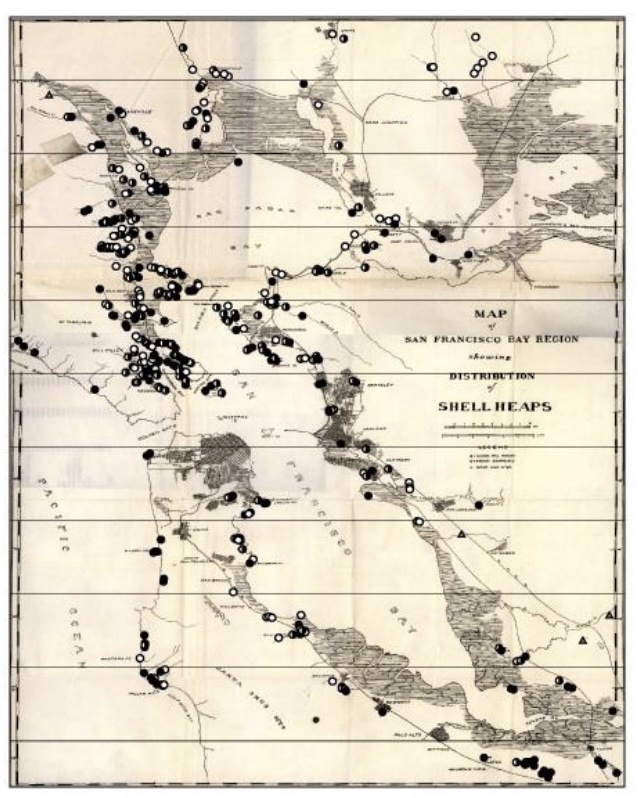

Shell mounds attest to the quantity of shellfish the people consumed. The mounds were more than shell repositories, however—they were also ceremonial places and burial sites holding thousands of years of human history. A 1909 survey of Bay Area shell mounds showed evidence of over 400, some of them huge. One mound in the East Bay measured 270 feet in diameter and was almost 30 feet deep in the center. Most of the shell mounds are now gone, bulldozed for development.

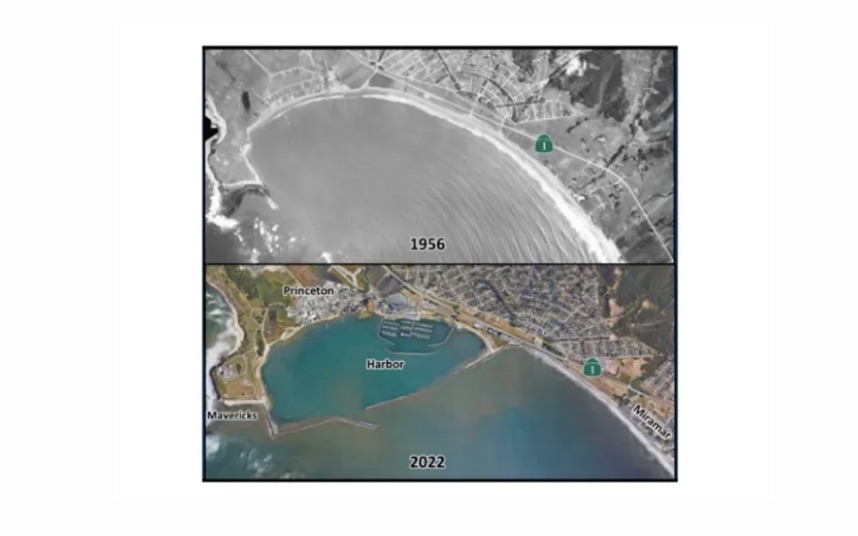

To catch surf fish, people set out in boats constructed of tule reeds tied into bundles and lashed together. Double-bladed paddles were used to propel the boats, whose lightness and buoyancy helped speed them across the water.

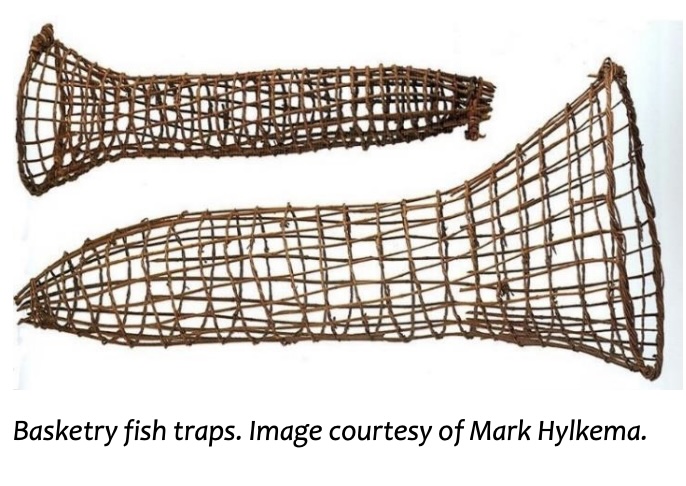

At the surf’s edge, men and women used conical basketry traps to scoop up huge numbers of smelt. They also caught smelt using two-person seine nets.

As a wave washed ashore, they planted the net’s two legs in the sand and hung on as the swiftly receding seawater drove hundreds of the tiny fish into the net.

The coast’s wild-running streams teemed with steelhead trout and salmon, and the people used nets and weirs to catch the bounty. Weirs were interwoven willow branches and tule reeds attached to stakes. The stakes were pounded into the streambed, arranged in a way that funneled the fish toward a harpooner or into a basketry trap. The coast’s sea and streams provided raw material for tools, currency that enabled trade items with inland tribal groups—and added deliciously to the people’s largely plant-based diet. Continuing traditional foodways today, descendants of the first people prepare dishes such as traditionally smoked salmon, broth with mussels, clams, and seaweed, and salad with watercress and pickleweed.

If you really love the Coastside Chronicles stories, written by Half Moon Bay History Association docents, perhaps you might like to donate or volunteer as a museum docent!?

More on Coastside History on Coastside Buzz