|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Lost Town of Purissima from mdragony on Vimeo.

About HMBHA

The varied history of the Coastside has been studied, shared and preserved by passionate volunteers for years. The Half Moon Bay History Association is dedicated to celebrating the rich history of the community’s passages through time with changing cultures, families, historic buildings and natural wonders.

Today we celebrate our legacy through a host of programs, which are designed to engage and educate all corners of the community. Visit our new history museum in downtown Half Moon Bay.

Our Mission

The mission of the Half Moon Bay History Association is to educate all as we preserve, honor and celebrate Coastside history.

History

Located on José María Alviso‘s Rancho Cañada de Verde y Arroyo de la Purisima in a rural area four miles (6 km) south of Half Moon Bay, the village was one of the earliest settlements on the San Mateo County coast, founded in an agricultural area in the early 1850s. The community was badly flooded by Purisima Creek in January 1862, the same month that much of northern California experienced its worst floods in history. Some fields and buildings were swept away.[1]

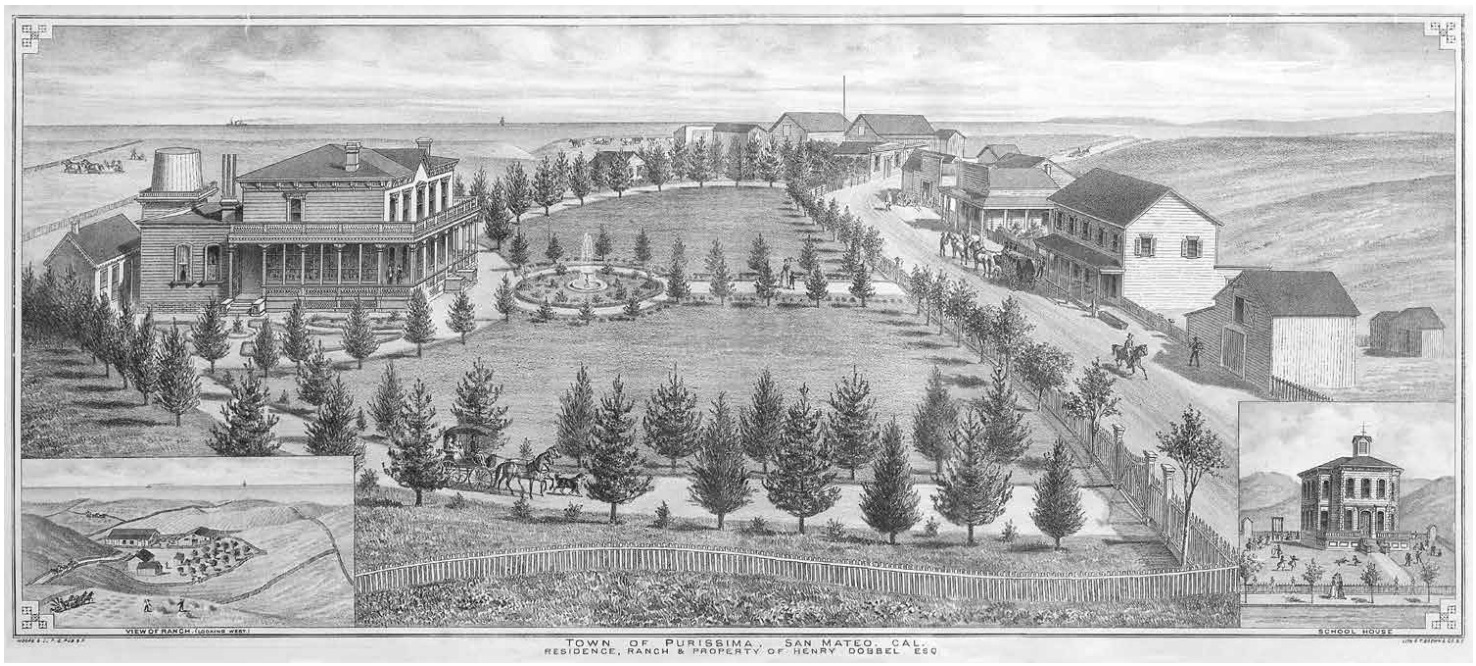

Henry Dobbel (born in the sovereign state of Holstein, then in a personal union with Denmark, on July 1, 1829; died in Purissima on December 22, 1891) came to California via Cape Horn in 1845. After working at odd jobs, and even running a San Francisco restaurant, Dobbel married German Margaret Roverkamf-Schroeder (born near Hanover, Kingdom of Hanover, in 1831; died in Purissima on September 3, 1885). She had come to California via the Isthmus of Panama. They bought a farm in the East Bay. In the 1860s, they sold their farm and bought 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) from John Purcell. They built a big, ornate house on the south bank of Purisima Creek. The house had two stories and 17 rooms; it boasted such innovations as gas lighting and running water. Dobbel employed 50 men who planted and harvested wheat, barley, and potatoes.

By the early 1870s, Purissima had a post office, several stores, a school, a one-story hotel known as Purissima House (owned by Richard Dougherty), and other buildings. The general store was built by Henry Husing. A lumber mill was constructed at the mouth of Purissima Canyon, to take advantage of the extensive redwood logging in the nearby Santa Cruz Mountains.

Oil was discovered near the village in the 1880s on George Shout’s land. However, hopes of an oil boom were dashed when only 20 barrels a day were produced. The U.S. Geological Survey has noted later efforts to drill for oil in the area, usually resulting in minor production.

Henry Dobbel bought the general store, only to encounter financial difficulties when he extended credit to many of his customers. Then there were a series of crop failures, which eventually impacted Dobbel and the entire community. Henry Dobbel went bankrupt and sold his estate in 1890 to Henry Cowell.[2] He remained in the area, however, and both he and his wife are buried in the village cemetery.

The Ocean Shore Railroad, which operated from San Francisco to Tunitas Creek from 1907 to 1920, included a stop at Purissima, as noted on a U.S. Geological Survey‘s Santa Cruz quadrangle map.

The Purissima Post Office opened in 1868, only to be discontinued in 1869. Then, in 1872, it reopened and continued to serve the community until 1901.[3]

Some buildings still remained as late as the 1930s, but the town was largely abandoned before World War II.[4] The 1940 U.S. Geological Survey map shows a few buildings and notes the “Purissima School.”[5] The 1943 map still shows the school. At that time, State Route 1 still passed directly through Purissima.[6] Today, Highway 1 runs farther west of the original route. Verde Road runs north from Lobitos to Purisima Creek Road; this is actually the original alignment of Highway 1.[7]According to the older maps, the school was located on the north side of what is now Verde Road, just east of Highway 1. The cemetery is in the woods bordered by Verde Road and Highway 1.

In 1939, the Federal Writers Project guidebook for California noted, “The village of Purisima, once a lively town on Jose Maria Alivso’s Rancho Canada y Arroyo de la Purisima, is ghostly and deserted now. Its weathered gray buildings stand among mosshung cypresses and eucalytpus trees, their windows broken, their stairs falling in, their facades rudely stuck with gay circus posters.”[8]

No clear reasons have been found for the demise of the community; presumably its remote location led some residents to move to Half Moon Bay or other communities. All that remains of Purissima today is the cemetery (still noted on U.S. Geological Survey maps) and a part of the school. Several farms surround the site. There are numerous evergreen trees and heavy vegetation at the site. Dayna Chalif, who has explored the Purissima Cemetery and researched historic archives, wrote, “Purissima was supposed to be the big town on the coast, [but it] was harder to get to.”[9] The failure of the Ocean Shore Railroad, which was intended to provide better access to the San Mateo County coast, may have hurt Purissima, although the village was later included on the original routing of Highway 1.

Until the 1950s, however, much of the San Mateo County coastal area remained sparsely settled and the few surviving communities were relatively small. With the dramatic rise of housing costs along San Francisco Bay (with average prices over $1 million in 2008), there has been greater incentive to build along the Pacific Ocean, resulting in the steady growth of Montara, Moss Beach, El Granada, Half Moon Bay, and Pescadero. This has done little for Purissima, which had long since vanished. Local newspaper articles have frequently mentioned that limited access to the area, primarily via Highways 1 and 92, has been a major factor in the slow growth. With the completion of the Devil’s Slide tunnel on Highway 1 in 2012, access to the coastal communities south of San Francisco has improved.[10]

In 2017, some restoration was begun of the site, with emphasis on cleaning up the cemetery, including access trails. Very little remains of the village besides the cemetery.[11] ~ Wikipedia