|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. From the Half Moon Bay History Association’s ~ Coastside Chronicles for Spring 2024 by Bill Scholtz. Donate or volunteer!

What is your favorite way to eat artichokes? Steamed with butter and lemon? Or perhaps roasted with olive oil and fresh herbs? Whatever your choice, these tasty thistles have quite an interesting history.

Artichokes are the edible buds of the thistle plant. They are native to the Mediterranean and cultivated over 2,000 years ago. While known throughout Europe, they were most loved in Italy and along the Mediterranean Coast.

Coming to America

By the 19th century, artichokes had arrived in the United States. However, they were not grown for human consumption. An article in San Mateo Times Gazette on January 28, 1878 described how artichokes were used to feed pigs as well as horses, cattle, and sheep.

So, how did artichokes end up being grown on the Coastside for people instead of animals? Cultivated to grow in a humid Mediterranean climate, artichokes grow well in the coastal climate.

According to the March 20, 1920 Pacific Rural Press, “Few places elsewhere In California will one find such beautiful black, rich, loamy, well-drained soil. It was originally the washings from the hills, mixed more or less with sand. Its present fertility is due to the trainloads of manure hauled from San Francisco and worked into the soil year after year.”

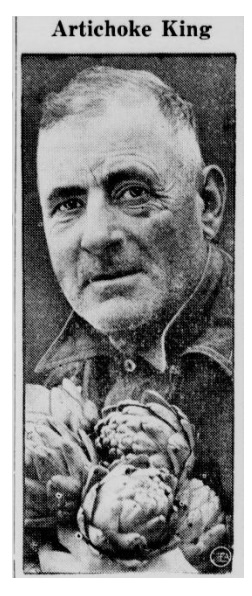

It is not clear who was first to grow them here. One story is that there was a test crop grown in Pedro Valley around the turn of the 20th century. What is known is that Dante Dianda was the first to grow large crops of artichokes in the area.

Dianda was born in Italy in 1875, immigrated to the United States around 1892, and moved to the Sacramento River where he started farming. When he got engaged to Silvia Belli, he decided to move due to a malaria problem in the region. He talked to a friend and decided to lease a farm near Half Moon Bay and start growing artichokes, something he knew nothing about. There were several other Italian farmers there already growing artichokes and they taught him how it was done.

By 1900 he had a farm on rented land in El Granada with ten men working for him, all from Italy. When the Ocean Shore Railroad came in, he bought the land he had been farming. He did very well and started to buy more and more land, much of which he rented out to other Italian artichoke farmers. He maintained his farm in El Granada until at least 1940. By 1950 he had retired, living with his wife in Boyes Hot Springs in Sonoma County.

Dianda was the first with the moniker “Artichoke King” in 1904 because he was the first to ship artichokes to New York. The artichokes were hauled over the hills by horse and wagon to San Mateo where they were loaded onto trains. He could have used the marketing slogan ‘Artichokes: not just for pigs anymore.’

Perhaps not surprisingly, artichoke farming was largely done by Italian immigrants. Even as late as 1930, of 36 farmers listed in the census as growers of artichokes, all but two were born in Italy or sons of Italian parents. The Coastside residents born in Italy accounted for 13% of the population of the Coastside, up from 6% in 1900. Most of the adult males farmed artichokes or Brussels sprouts.

Artichokes are perennials and as such, typically bore fruit in the end of summer or early fall putting them in competition for acreage against all other vegetables. But the growers discovered that mowing the plants down to the ground would delay flowering and harvesting, enabling them to extend the harvest to between October and May.

Even though most native-born Americans had never eaten an artichoke, they were a very profitable crop. There were enough Italians in the US for the demand to far exceed what Dianda and others could produce. Farms sprung up from Pacifica all the way down to Monterey. But the epicenter for the product remained on the Coastside at least into the 1930s.

To increase demand, growers created the California Artichoke Producers’ Association. By 1912, the association had agents in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, Kansas City, St. Louis, and New Orleans. Their job was to educate consumers on the value and preparation of the artichoke.

The Coastside production was growing fast. By 1912, there were 200 railcar loads worth of artichokes shipped for a total value of $1,000,000. By 1920 there were between five and six hundred carloads shipped from San Mateo County with 95% of the artichokes grown between Pacifica and Santa Cruz.

Time to Organize

By 1917 it was time for Coastside growers to have their own association. John Debenedetti was the son of Joseph Debenedetti, the county supervisor who built both the concrete bridge and Debenedetti building in Half Moon Bay. John, soon to become the next “Artichoke King,” was not a farmer, instead a banker and financier, but exactly what the association needed.

The association was named the Half Moon Bay-Coastside Artichoke Growers Association, later shortened to the Half Moon Bay Growers Association.

Their work focused on making the farmers’ jobs easier, including market development, shipping, packing, canning, and supplying labor.

One packing plant was located at 845 Main Street in Half Moon Bay for 70 years. Today, fittingly, it is Pasta Moon, an Italian restaurant.

One of the first things DeBenedetti did was to contract with American Express to get products to the east coast faster. American Express started out as the FedEx of its day, able to get artichokes east in a few days rather than the few weeks other shippers required.

Debenedetti also increased the labor supply by arranging for hundreds of Italians, mostly from the Genoa area where his family originated, to come to the Coastside. He arranged for their housing and work and for this his son said, “he was given the Cavalier’s Cross, which I think is equivalent to knighthood or something, by the King of Italy.”

After about 15 years of running the association John must have caught “the bug” as by the early 1930s he retired from his position and he and his son started farming artichokes. On about 1,000 acres, they farmed artichokes, Brussels sprouts, asparagus, and other vegetables. They branded their vegetables “Fog Kist.”

Where There is Money, There is Crime

While the crop was very lucrative, farmers and farm laborers were not getting rich. Throughout the Coastside, about 50% of the farmers owned the land they worked, but for Italian farmers, it was well under 10%. They leased farms from others, and rents were based on the value of the crops being grown.

Some leased acreage from the association, others from farmers who realized they could make more money leasing their land for artichokes, and the rest rented from wealthy landowners, most notable of whom was John Patroni.

John, or Giovanni Patroni, was born in 1878 in Italy and came to the US around 1901. Today he is best known as the owner of Patroni House (where the Half Moon Bay Brewing Company is located today), Patroni’s Wharf, and his colorful life as a smuggler during Prohibition. While he owned or controlled vast tracks of land in and around El Granada that he rented to Italian immigrants he never earned the title of “King,” but he was known as “Boss Patroni.”

Enter the Mafia

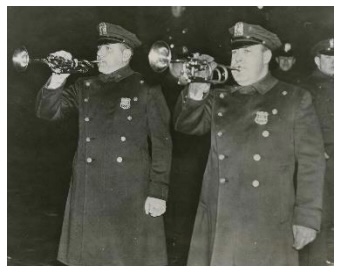

On December 21, 1935 at 6:50 am, two New York City Police Department trumpeters with a large police entourage behind them marched into the Bronx Terminal Market in New York City. They were heralding the arrival of first-generation Italian American and first-term mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. He climbed onto the back of a vegetable truck and announced a ban on the sale of artichokes in New York City. He said that “an emergency exists which threatens the peace and order of the city… I know you dealers are honest men, and as long as I am Mayor, no racketeer, thug or punk is going to intimidate you.”

The ban was intended to break the Mafia’s control of the artichoke market and was combined with several indictments. Three days later arrests were made, the ban was lifted, and LaGuardia declared victory.

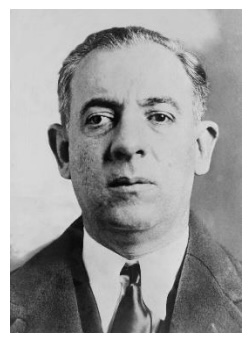

Mob involvement in artichokes started early on. The Morello-Terranova family, under the direction of Sicily born Ciro Terranova, imposed a tax of between $25 and $50 on every train carload of artichokes entering the city in the 1910s.

By the 1920s he had set up a corporation, Union Pacific Produce Company, through which all artichokes had to be shipped. He limited the supply coming into New York and forced the growers to accept low prices. He then sold them to wholesalers for a huge markup. By the 1930s this was bringing in about $330,000 a year. It earned Terranova the third crown of “Artichoke King.”

By 1930 he had started physically intimidating the California growers. In what became known as the “artichoke war,” he was hijacking truckloads of artichokes in both San Mateo and Monterey Counties. During the first week of January in 1931 alone over $10,000 worth of artichokes were stolen by the mob from the Coastside. In some cases, plants were hacked to the ground with machetes.

The loss and damage were estimated to have cost the California growers about $100,000 in 1930. All this was to force the growers to sell through the Union Pacific Produce Company and sell for prices that Terranova dictated.

Intimidation was not restricted to the west coast. Frank Mortori was a NYC vegetable merchant who refused to buy from the mob. One day, four of his drivers were abducted and badly beaten. According to the head of the California growers, people who were investigating the racketeering were threatened with death unless they “left town in a hurry.”

By the time of the artichoke ban Terranova had already been pushed out of the artichoke business by younger and more aggressive Mafia bosses. At the time of his death in 1938 the “King” was penniless.

As part of the ban, LaGuardia asked the growers of California to start selling to independent wholesalers rather than the mob when the ban was lifted. They responded through a newspaper reporter from San Francisco that until the parties were convicted and in prison it was too dangerous to bypass the mob. They said, “the growers will not care to risk retribution in physical violence and property damage.” LaGuardia forwarded that message to J Edgar Hoover.

The ban was coupled with several arrests, but what ultimately broke up the Mafia control of artichokes was the dissolution of their intermediary Union Pacific Produce Company.

The growers of the Coastside sent a letter to LaGuardia thanking him profusely for breaking up the monopoly. It was signed by 19 Coastside residents, the first and largest signature was that of Dante Dianda, our first “Artichoke King.”

When the ban was lifted, LaGuardia reached out to restaurants and asked them to include artichokes in their menus. That request, plus the press coverage of the ban boosted the sale of artichokes in New York City.

Coastside Dethroned

During the first 35 years of artichokes growing on the Coastside, the community prospered. However, the Italians who did all the work didn’t benefit as much. The immigrant farmers were squeezed on one side by the landowners and on the other side by the Mafia. But by 1935 that was changing.

From the 1930 census, farm ownership was up to 30% and the breaking of the Mafia monopoly allowed them to get more money for the artichokes.

However, for some, that was too little too late. By the 1930s, the bulk of the artichoke production had started to move south. The Coastside is an excellent place to grow artichokes, but northern Monterey County is even better. The Coastside was the first artichoke capital of the United States, if not the world. But like so many other things, those days are gone.

Half Moon Bay History Association’s ~ Coastside Chronicles for Spring 2024 by Bill Scholtz.

Donate or volunteer!