|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. From the Half Moon Bay History Association, June 2023.

The areas in which we live—and where our ancestors originated—influence our food preferences. Look back into your life and remember family dinners, picnics, school-lunch-pail food, and the ethnicity of the meals you remember with fondness.

This article approaches how Coastside peoples—the Ohlone, Spanish, Californios, Gold Rushers, and World War II folks in the area—secured their food, and the tools and the cooking systems they used to prepare it.

The Ohlone—the First Coastsiders

The diverse landscape and their attachment to the land led the Ohlone people, who have inhabited our coastal areas for over 14,000 years, to enjoy an abundant natural supply of resources. To ensure the growth of edible plants, the Ohlone used land-management techniques such as pruning, coppicing, weeding, planting, and seasonal burning.

The book Tending the Wild, by M. Kat Anderson, shows a food pyramid of how the Ohlone thrived on what they nurtured from the land. In the largest group are seeds and grains; then bulbs, corns, rhizomes, taproots, tubers; then upwards to leaves and stems; fleshy fruits are at the top.

The Ohlone not only used available vegetation for food, they secured additional proteins from shellfish, ocean fish, rabbit, rattlesnake, bear, deer, gop hers, squirrels, birds, lizards, amphibians, and insects.

hers, squirrels, birds, lizards, amphibians, and insects.

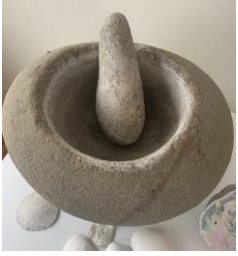

The heroes of the Ohlone land of plenty might have been the acorn and the mortar and pestle that women used to grind acorns. The mortar was a stone bowl created through pure perseverance. A woman worked for months, and maybe even years, to create a smooth bowl. She created a pestle to use as a grinding tool, shaping a hard stone to fit the bowl. These mortars and pestles were passed to the next generations as heirlooms.

Mortars and pestles were used in all the places where the tribes lived during the year. When the tribe moved to another seasonal harvest area, the women turned the mortars upside down, to be found when they returned. The Half Moon Bay History Association’s Coastside History Museum, 505 Johnston Street, displays an example of a mortar and pestle that shows the result of an Ohlone woman’s hard work. Creating this mortar would have taken at least a year of daily work.

Other necessary tools besides the mortar and pestle were knives made from obsidian or local Monterey chert to form projectile points and scrapers. Wood, plant fibers, animal bones, skins, feathers, shells, and furs were used for clothing and to make storage containers. Baskets were used as containers.

Some were woven so tightly they could hold liquids—for example, acorn flour was cooked in water-tight baskets. A woman ground acorns using her mortar and pestle, then leached the flour by running water over it in a flat basket, to remove the bitter tannin. The cooking came next—the flour was placed in a tight basket filled with water. The woman heated stones and with two shaped sticks, dipped them into water to wash off the ashes, and dropped them into the acorn mush. She constantly moved the stones to keep them from burning the basket. The mush boiled, the stones were removed, and it was served as a soup or porridge. Acorn flat bread and seedcakes were also made, on top of a hot slab of rock.

With food sources abundantly available, you might wonder about sugar and salt to enhance the meal. There would be no disappointment, as one source for salt was kelp, while a sugar source came from the pitch of pine trees, or from willows. Everything a person needed to thrive with good health was right there on the land.

If you wonder what goodness resulted from the gathering and cooking, peruse the PBS program Native Voices for inspiration on traditional Ohlone foods. The program shows how to make an Ohlone salad, using native greens from the oak woodlands. The 2018 show was produced at Café Ohlone in Berkeley by mak-‘amham, an organization that is reviving traditional Ohlone foods. Vincent Medina, a descendant of the Muwekma Ohlone, and Louis Trevino, a descendant of the Rumsen Ohlone, are partners in the restaurant.

The Spanish Arrive on the Coastside

The Ohlone saw the beginning of a drastic change in their lives in 1769, when Spanish explorer Captain Gaspar de Portolá and his expedition arrived. The people must have been astonished at the explorers who came upon their homeland, but they were hospitable with the strangers. They shared food with the Spaniards, who were suffering from hunger, and from scurvy for lack of fruits and vegetables.

Spain claimed Alta California, and foreign control of the land began. Mexico won independence from Spain in 1822, and the Mexican government granted large tracts of land to military and civic leaders.

The grantees developed ranchos on the land, where their cattle grazed and where the barbecue became the focus of feasts. These early settlers and their descendants, known as Californios, included Spanish dishes in their cooking using such ingredients as olive oil, grapes, and almonds. Early Californio recipes also included ingredients from Mexico such as corn, tomatoes, squash, and chiles. And they included local foods eaten by the Ohlone, such as purslane and yerba buena (a mint).

The recipe book El cocinero español (the Spanish Cook) gives us a fascinating look at the food of the Californios. Published in 1898 by Encarnación Pinedo, it was the first cookbook written by a Latina in the United States. (Selections from the book are brought to life by editor and translator Don Strehl in Encarnacion’s Kitchen—Recipes from Nineteenth Century California.)

Pinedo preserved her family recipes to save her culture for her nieces, who were growing up in an Anglo household. She disdained Yankee cooking. Her recipes, which were influenced by Spanish, Italian, and French cuisine, represent her idea of classical Californio tradition.

The book is loaded with hundreds of recipes of all kinds, including an astounding process of making traditional mole (a type of sauce). Ingredients used in various mole recipes include cinnamon, cloves, almonds, sesame seeds, peanuts, chiles, and sugar. Depending on the mole that will go with the chosen meat, the necessary ingredients are ground together and cooked in lard.

Gold!

The lust for gold created a thirst for riches in California in 1848, after James W. Marshall discovered gold in Coloma. Getting to California any way they could, the 49ers loaded up wagons and headed to the state in multitudes from all over the United States, joining men from other parts of the world.

Among the ‘49ers was James Johnston, who came to California from Ohio. He reportedly had some success in mining, but soon moved on. In 1853, he bought part of Rancho Miramontes and built a house using a New England-style “saltbox” design. The house remains a Coastside landmark on its hillside south of Half Moon Bay.

The journey to California created hardships for travelers, the biggest one being food difficulties. The men faced a monotonous culinary selection of beans, bacon, biscuits, flour, and coffee. Scurvy became commonplace because of the shortage of fruits and vegetables.

With hardships from weather, sickness, broken-down wagons or sick and dying animals, men looked for food wherever hunger led them. For example, Joseph Goldsborough Bruff, traveling and hungry, was delighted to discover innumerable large black mice. He declared them to be “fat and very soft and silky.” After roasting them, he found them “very tender and sweet.”

Gold rushers/travelers who were fortunate to have made it to San Francisco were met with more food challenges. “…culinary self-sufficiency proved important in the California gold rush, where only eight percent of the new population was made up of women, with even smaller numbers in mining areas,” notes Food of the California Gold Rush.

Hungry men created a cultural diffusion from various sources—then, welcomed into the culinary options, came sourdough bread. It got its official start when Isadore Boudin, a French baker, opened his San Francisco bakery in 1849.

The Coastside Grows

The gold rush kicked off a huge migration that, over the years, continued to bring people from many cultures. The Coastside’s rich soil and temperate climate attracted a diverse agricultural populace, all contributing to a vibrant cultural stew that celebrated food traditions. Italians introduced the first artichokes for commercial sale; American, Portuguese, and Italian-Swiss immigrants started dairies; a Japanese immigrant started a flower nursery, providing flowers for the table.

In Coastside towns, merchants opened shops and saloons to supply the growing population. People fished the streams and the ocean. Canneries opened in Princeton to preserve the bounty from land and sea.

In the early 20th century, the Ocean Shore railroad took Coastside produce to San Francisco markets. The railroad also brought prospective buyers for the planned land boom, providing free lunch baskets for the trip down the coast.

Food traditions flavoring the Coastside c0ntinue today. For example, the Portuguese I.D.E.S. (Irmandade de Civino Espirito Santo—Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit), organized in Half Moon Bay in 1871, feeds the community during its yearly festa with linguiça and with the specialty of beef cooked in a sauce of wine, water, and secret spices.

WAR !!

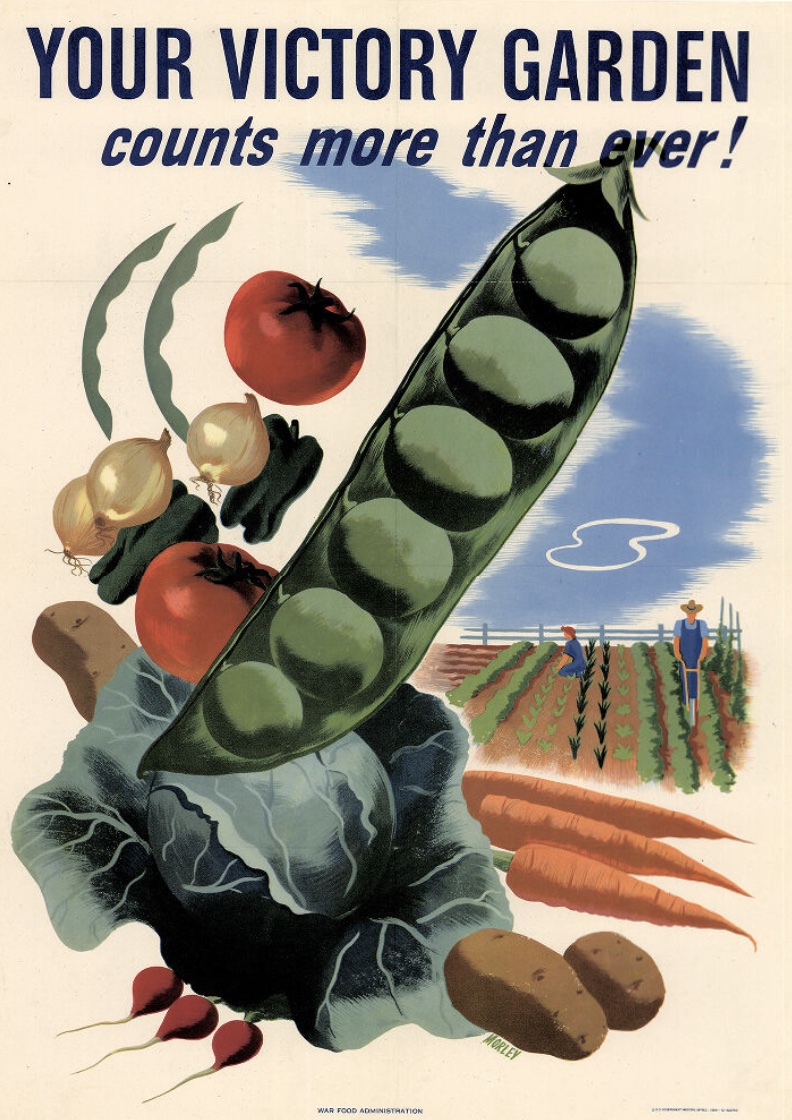

World War II brought Americans restrictions on food and other commodities, and they were asked to make sacrifices in many ways. Food rationing was one of those ways, because foods were diverted to the war effort. War also disrupted trade, limiting the availability of some goods.

On August 28, 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt created the Office of Price Administration (OPA), whose main responsibility was to place a ceiling on prices of most goods, and to limit consumption and hoarding. The effort began with coupons: red coupons were issued for meat, butter and fats. Blue coupons were for canned and processed foods. Americans received their first ration cards in May 1942. The first card was for supplies such as gasoline, butter, sugar and canned milk.

Besides rationing, the government encouraged citizens to strain used cooking grease to sell to a participating butcher, because one pound of fat contained enough glycerin to make one pound of black powder, for use in bomb-building. The butcher paid 4 cents for one pound of grease.

Victory Gardens sprang up everywhere, producing vegetables. Victory Gardens were planted in back yards, on vacant lots, rooftops, and even in some schools.

Coastside History Museum Docent Paul McReynolds remembers the times during the war with his mother, father, and four brothers. He said that his dad did most of the cooking and he mentioned the canned product, Spam. “It was probably fried,” he said, without adding any fond memories of it. And his dad made something like Salisbury steak. “He’d use a big piece of hamburger and he’d put canned cream corn on top of the meat and put it under the broiler.”

McReynolds’ father also made 6 to 7 dozen cookies every Sunday, so the five boys would have them for school lunches. “We always took our lunches to school in paper sacks.” Breakfast always consisted of cooked cereal, such as Cream of Wheat.

In place of rationed butter, there was a block of white margarine that had an orange capsule on top. The orange color had to be worked into the margarine, to turn it into the color of butter. “We had Nucoa,” McReynolds said, which was also a substitute for butter, that came with some “sprinkly stuff that had to be worked into it. That was difficult.” The McReynolds family never skipped dessert, for they always had canned fruit, like peaches or pears. Oh, and ice cream cones, McReynolds remembers, were 5 cents at the ice cream store on Geneva Ave in San Francisco.

Using coupons to control food, as well as saving rubber and other items, brought citizens working together for the country’s war efforts. Neighbors helped neighbors, and very little was wasted. The motto, perpetuated by the government for the rationing days was, “Use it up. Wear it out. Make it do. Or do without.”

Well, that’s Coastside food through the ages—you may note the current food changes we see today. Is our food healthy? Does food gathering and preparation create what you need? Food for thought!

by Laureen Diephof

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.coastsidebuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Food_through_the_ages.pdf”]