|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ARTICLE. From the Half Moon Bay History Association’s “Coastside Chronicles” written by Marc Strohlein. Donate or volunteer!

The biggest challenge in traveling today’s San Mateo coast is doing battle with all the other vehicles vying for the same roadway. Vexing perhaps, but it is instructive to look back 100 years at the much different challenges faced by traveling Coastsiders.

In the early 1900s, the coast, like much of the country, was undergoing a transportation metamorphosis. Students, along with their parents and neighbors, witnessed an era where walking, bicycling, horse-riding, buggies, wagons, cars, ships, and a railroad all co-existed, albeit not always in harmony.

At first blush, you might think that the Half Moon Bay High School students and their parents had a cornucopia of transportation options, but digging deeper reveals the challenges and limitations. Early road conditions were poor, and those roads and paths often followed in the footpaths that the Ohlone Indigenous people had trod many years earlier.

Coastal residents also faced unique geographical challenges, hemmed in by the ocean to the west, and by mountains to the north and east. A one-hour journey over the hill, today, is considered onerous—in the late 1800s a wagon trip from Half Moon Bay to San Mateo was an all-day affair.

Life for farmers was not much easier as they had a “tough row to hoe” (early farm-speak for an extremely difficult time) in getting produce to market in San Mateo or San Francisco. They faced long, arduous wagon trips, or the use of treacherous, even deadly, ocean shipping. With no harbors or sheltered coves, a succession of wharves and chutes were built by visionaries including Josiah Ames, Alexander Gordon, Henry Cowell, James Denniston, and John Patroni. Unfortunately, all were subject to the capricious whims of weather and ocean conditions and were ultimately destroyed.

Fortunately for travelers and farmers alike, in 1905, the Ocean Shore Railroad started to lay tracks with a planned route from San Francisco to Santa Cruz. The railroad was an audacious scheme, involving laying track over what is now aptly called Devil’s Slide and miles of rocky, unstable terrain. Adding to problems, the 1906 earthquake wreaked havoc, dumping several thousand feet of track and costly construction equipment into the ocean.

The railroad was initially a boon for farmers now able to get produce to markets. It was also a magnet for realtors and developers who sold lots in the towns that began springing up along the train route. And competition was too much for stagecoach lines as the last stage run to Half Moon Bay ran on August 31st, 1909. The railroad ran on a shoestring budget. The tracks ran only from San Francisco to Tunitas Creek and from Santa Cruz to Davenport, leaving a gap in the middle. That required the use of wagons and later Stanley Steamer 12-passenger Mountain Wagons to bridge the gap.

Ultimately, the railroad failed, falling victim to undercapitalization, destructive weather events, costly

operations, and most of all, competition from automobiles. In Granada, Synonym for Paradise, Barbara Vanderwerf described the unhappy end of the railroad, stating “Towards the end of its days on the Coastside, the Ocean Shore Railroad could do nothing right. Schedules were never met; trains broke down and the track washed out.” Vanderwerf noted that “Coastsiders bought their own automobiles, abandoning the train to vacationers and produce.” Attesting to the early popularity of autos, Mitchell P. Postel, in San Mateo County: A Sesquicentennial History, reports that the first automobile meet in California history started in San Francisco and ended at Crystal Springs dam, in 1902.

The railroad played a big role in opening up the coast to tourists, while affording easy access to San Francisco for work, shopping, and entertainment, but automobiles were a much bigger phenomenon—once drivable roads were established. The most challenging route was over Montara Mountain, via a series of roads dating back to the Portolá Expedition in 1769.

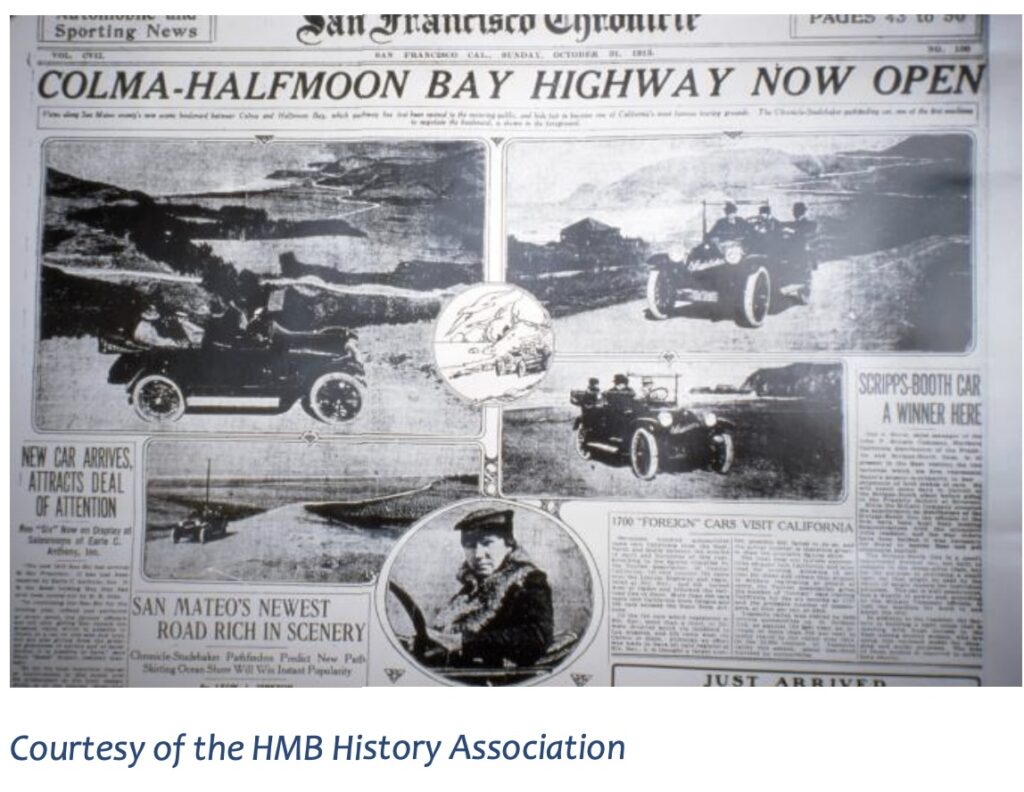

A series of Pedro Mountain crossings followed including the Half Moon Bay – Colma Road, which crossed over the mountain close to the ocean on very steep and rutted switchbacks with grades of up to 24%. Motoring magazine warned in 1913, “Pedro Mountain Road is in such poor condition that anyone going this way is simply inviting disaster.”

The danger was underscored by a large sign that read: “DANGEROUS FOR AUTOMOBILES—TAKE ROAD VIA SAN MATEO.” Frustrated motorists formed the Coastside Promotion Association which joined with the San Mateo County Development Association, and in 1913 voters passed a bond issue that included money for a new road named the Coastside Boulevard. San Francisco car owners also apparently helped provide impetus for better road access to the coast. The March 31, 1912, San Francisco Examiner noted that automobilists were tired of “confining their outings to drives through the Presidio and Golden Gate Park, rather than make the trip out of the city over roads in their present condition.”

The Coastside Boulevard (Highway 57) route ran up from Higgins Road in Pacifica and provided a more accessible route for motorists. Interestingly, it was promoted similarly to the railroad by the Coast Side Comet newspaper published in Moss Beach by George Dunn. Ironically, the paper had been an early promoter of the Ocean Shore Railroad and the developments along the coast, but later extolled the virtues of automobiles, yet ended publication in 1920 when the railroad folded.

The June 12, 1914, the Comet stated “Believe me, when the Coastside Boulevard over Montara Mountain is thrown open to San Francisco Motorists, you will see them coming over that hilltop north of Farallone and Montara once every second the clock ticks. And why not?” As for “why not?” despite the Comet’s accolades, the Boulevard had steep inclines and tight curves, and disintegrated rapidly. It was deemed unsafe and in need of reconstruction in 1916 after fierce winter storms that also washed-out Ocean Shore tracks.

Car ownership in California increased from 36,146 in 1910 to almost 533,000 in 1920, in part thanks to the introduction of Ford’s Model T in 1908. The Comet helpfully offered that “Anyone can own a little Ford and The Ford will take its full load to the city over the Boulevard in less than forty minutes.”

Like many new technologies, the introduction of the automobile was not without its challenges and detractors. Cars were noisy and frightened horses. Gas stations were nonexistent, so owners either had underground storage tanks or bought gas in small quantities from hardware stores.

Early automobiles required a complex starting procedure culminating with hand cranking the engine. Kickbacks could break wrists or arms. Early motorists also had to be self-reliant in repairing their autos, but blacksmiths, bicycle shops, machinists, and horseand-buggy dealers eventually, if reluctantly moved to the auto trade as this ad from the 1914 yearbook shows.

By 1913, The Coast Side Comet described the ascending popularity of autos and motorcycles, stating “V. J. Belknap and wife have returned from the northern part of the state. They motored north in their new Stanley Steamer. Pete Gianni has just bought a new motorcycle and you bet he is enjoying the use of it. Matt Joseph has purchased a 28-horsepower Buick automobile, and all the girls around here are enjoying themselves out riding with Matt.”

Yet life for motorists was not free and easy as the February 24th, 1911 paper noted that San Mateo County had hired three “motorcycle” policemen who were paid $7.50 per day, and ten dollars for every conviction of “speeding automobilists.”

In just a few short years, the class of 1910 witnessed an amazing transformation that changed their lives. Imagine a young person’s excitement as the railroad and then autos moved them from being virtually marooned on the coast to having ready access to the wonders of San Francisco and the towns “over the hill.”

The automobile brought almost unlimited mobility along with some notable downsides including accidents, air pollution, and traffic jams but it’s safe to say that t students, along with their descendants up to the present day, would not go back to all-day trips on jouncing wagons to journey over the hill or into San Francisco.