|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

PRESS RELEASE. From the California Department of Fish and Wildlife on December 15th, 2021.

View of Egg Rock from the mainland

photo by P. Gonzales

In 1986, a devastating oil spill wiped out an entire population of more than 3,000 common murres nesting on Egg Rock off the coast of San Mateo County. But this restoration story has a happy ending – over the last quarter century, the common murre population here has rebounded to more than 2,000 birds. Read on to find out how state and federal interventions assisted in this comeback…

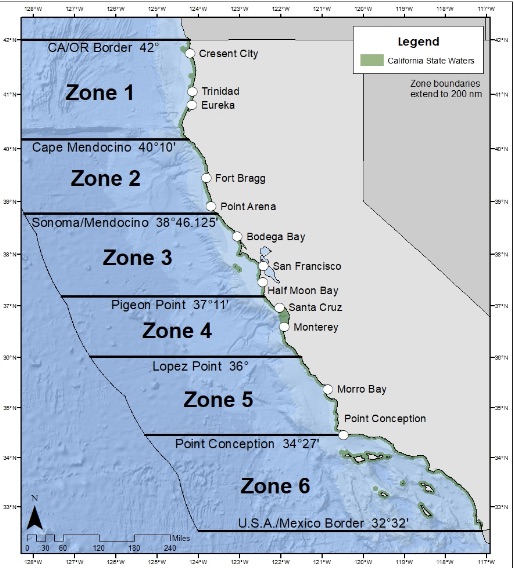

The Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA), passed by the California State Legislature in 1999, made California the first state in the country to create an interconnected network of marine protected areas (MPAs) aimed at sustaining and enhancing marine species and their habitats. These MPAs were planned, approved, and implemented in a region-by-region process that integrated public discussion, stakeholder participation, and scientific guidance. The MPAs’ allowed uses and levels of protection varied depending on their designations.

Map of Egg (Devil’s Slide) Rock to Devil’s Slide Special Closure

(click to enlarge)CDFW map

Over the course of the regional planning processes along the state’s coast, 14 special closures were also created to achieve the goals of the MLPA and complement the 124 MPAs in the MPA Network. Special closures are not technically MPAs; instead, these small areas prohibit access and/or restrict boating activities to protect seabird nesting sites or marine mammal haul-out areas. Although special closures are less common and cover a much smaller area than MPAs, they serve a very important purpose in the MPA Network. Let’s take a closer look at one of them: Egg (Devil’s Slide) Rock to Devil’s Slide Special Closure.

Every spring and summer, hundreds of somewhat penguin-like birds descend upon Egg Rock, a cluster of rocks jutting out of the water near the sleepy seaside town of Pacifica, about ten miles south of San Francisco. There, they huddle together in tightly packed colonies to breed and raise their young. These birds, called common murres (pronounced ‘myur’), are a type of pelagic seabird, meaning they spend most of their lives over the open ocean. They typically come back to dry land only to raise young. Once they find a safe rock, island, or cliff away from predators, murres will often return to the same spot year after year, seemingly with a “if it ain’t broke, why fix it” mentality.

Common murres don’t build nests. Instead, they lay a single egg directly on the bare rock. This may seem risky, but the egg is so pointed on one end that it will roll in a circle if pushed. Scientists think that this adaptation may keep eggs from rolling off the coastal cliffs and rocks where murres lay their eggs.

Their ocean-centered lifestyle sounds laid back, but it also makes common murres especially vulnerable to the adverse effects of certain fishing practices and marine pollution. For example, gill nets killed tens of thousands of common murres statewide before California began imposing restrictions on gill net use in 1987. Oil spills, such as the extended Luckenbach incident in the Gulf of the Farallones, and the 1998 Command spill between San Francisco and Monterey counties, also led to massive population declines. At Egg Rock in particular, the entire colony of more than 3,000 breeding common murres was decimated in 1986 when the Apex Houston oil tanker leaked more than 25,000 gallons of crude oil into the ocean between Marin and Monterey counties.

Despite all this, common murres are one of the most abundant seabirds found at Egg Rock today, with hundreds of breeding pairs raising young on the craggy cliffs. How did they bounce back from the perilous situation of just a few decades ago?

In 1996, a group of scientists formed the Common Murre Restoration Project. Led by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the team sought to increase seabird populations at sites along the central and north central California coast, with the primary objective of restoring the Egg Rock colony.

Since common murres love to forage and nest together, they are much more likely to nest in areas where other murres are already present. But even murres don’t want to be the first guest at the party, so scientists had to find ways to trick them into thinking their fellow birds were already there. To do so, they employed social attraction techniques, such as playing recordings of common murre calls through large speakers and setting out common murre decoys around the rocks. They even used strategically placed mirrors to make the rocks appear already occupied to murres passing by. The ruse worked, and common murres began returning to Egg Rock. The population grew from six breeding pairs in the program’s first year to over 2,000 birds in 2015.

The 1999 passage of the landmark MLPA laid the groundwork for additional protection for the common murres nesting at Egg Rock. During the North Central Coast MPA planning process, Egg (Devil’s Slide) Rock to Devil’s Slide was proposed as a special closure. Scientists, government officials, and members of the public agreed that access should be prohibited between the rock and the mainland, as well as in any area within 300 feet of the rock, to minimize human disturbance to the thousands of seabirds that nest there every year.

In 2010, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), as the primary agency responsible for implementing the MLPA, coordinated with key partners to implement baseline monitoring of a number of species and habitats to compare to the years following MPA establishment. From 2010 to 2012 along the north central coast, researchers from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and Point Blue Conservation Science found that 91 percent of the region’s breeding seabirds nested in special closures like the one around Egg Rock. They observed almost immediate effects from the 2010 establishment of the special closure. In surveys conducted prior to 2010, rates of seabird disturbance by close-approaching vessels were two to eight times higher than in 2010 and 2011 (after MPA establishment), indicating that the special closure was already providing effective protection to the seabirds nesting and resting there.

Reducing direct disturbance is the primary way that the MPA Network’s special closures can help seabirds like the common murre. When people or vessels get too close to a nesting site, the natural foraging and resting behaviors of seabirds may be interrupted. Disturbance during the nesting season can also scare parents away, leaving eggs and chicks vulnerable to predators and other hazards. When disturbance is reduced, seabirds have the freedom to eat, nest, and rest safely and securely, and more birds are likely to come back over the longer term. CDFW continues to coordinate with partners like the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the Seabird Protection Network to monitor and raise awareness about seabird populations along the coast.

Today, this 0.05-square mile special closure keeps the area off-limits to boat traffic year round, but you can bring your binoculars and check out the birds from the nearby Devil’s Slide Trail. This segment of former roadway is now a 1.3-mile trail that can be enjoyed by hikers, bikers, and equestrians, and will eventually be part of the 1,200-mile-long California Coastal Trail between Oregon and Mexico. Free parking is available at both ends of the Devil’s Slide Trail.

If you visit this special closure from the water, be sure to stay at least 300 feet seaward of any of the three rocks comprising Egg (Devil’s Slide) Rock, and keep an eye out for signs of distress from seabirds. If the birds suddenly change their behavior, start bobbing their heads, or begin flying away, you may be too close! If you see others bothering seabirds, you can submit an anonymous report to Californians Turn in Poachers and Polluters (CalTIP).

If you visit this special closure from the water, be sure to stay at least 300 feet seaward of any of the three rocks comprising Egg (Devil’s Slide) Rock, and keep an eye out for signs of distress from seabirds. If the birds suddenly change their behavior, start bobbing their heads, or begin flying away, you may be too close! If you see others bothering seabirds, you can submit an anonymous report to Californians Turn in Poachers and Polluters (CalTIP).

Now, take a tip from the common murre – gather a bunch of friends and go enjoy a special place along California’s beautiful coast!

post by Kara Gonzales, CDFW Environmental Scientist