|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

VIDEO. From the City of Half Moon Bay City Council meeting on Tuesday, March 15th, 2022 at 7:00pm by Zoom.

Community Development Director, Jill Ekas, introduces housing consultant, Paul Penniger, from Baird and Driskell (B&D).

From the Housing Update Staff Report

880 Stone Pine Road: The City recently purchased this property with the primary intent to continue to use the site for the City’s corporation yard. Because the site is relatively large, City Council expressed interest in completing a feasibility study of potential development of affordable housing on another portion of the site. City staff has overseen two related efforts to assess feasibility.

- Environmental and Hazards Constraints: An environmental and hazards constraint assessment is nearly complete. It was prepared by the City’s environmental consultant (SWCA) who has been working on the environmental review in fulfillment of California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) requirements for the corporation yard permitting. They will complete the report once the corporation yard project review is complete. Numerous constraints affect the site and include biological resources and various hazards. Staff and the environmental consultant have worked to address these constraints with the intent of improving the feasibility for developing a portion of the site with affordable housing.

- Financing and Development Constraints: The City’s housing consultant has conducted a parallel feasibility assessment, primarily related to the ability to finance development on this site. The biological and hazard constraints affect financing options. The preferred financing approach is through tax credits. Because the site could potentially support about 50 units and is well-located, it could compete well for this type of financing. Unfortunately, a recent report about the condition of the Pilarcitos Dam, which is an SFPUC facility, and down stream inundation in the event of dam failure presents risk for financing under the current conditions. While dam failure is unlikely, it can be life threatening. A dam improvement project is included in the SFPUC CIP program, with expenditures budgeted through 2030, although construction is not anticipated to commence in the next five years. The City’s housing consultant recommends that the City consider including this site in the cycle 6 Housing Element and monitor progress on the dam improvement project. As the project moves ahead, the City will be in a much better position to move forward with an affordable housing development on this site.

Full Staff Report

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.coastsidebuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/STAFF_REPORT_Housing_Updates_March_15_2022_final.pdf”]

Pilarcitos Creek on Wikipedia

SFPUC’s Pilarcitos’ Stone Dam

CELEBRATION! La Nebbia Winery is Back After the Hwy 92 Flooding in December 2021

FEBRUARY 23, 2022

Spring Valley Water Company

From the SFPUC website

Spring Valley Water Company

Historical Essay

By Libby Ingalls

Adapted from “Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin'” by Gray Brechin

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Sunol Water Temple, straddling the Hetch Hetchy system and Alameda Creek, one of the original waterways owned by the private Spring Valley Water Company before municipalization. Spring Valley Water Company built this temple in 1910, as seen in the inscription on the next image.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Photo: Chris Carlsson

| Between the mid 1860s and 1930, San Francisco’s water supply was controlled by the Spring Valley Water Company. As one of the most powerful private monopolies in the state, Spring Valley was controlled by, and used largely for the benefit of, the local land barons and financiers who authorized the development of a wide variety of often-destructive hydrologic projects. Efforts to de-privatize the city’s water supply began under the Progressive mayoral administration of James Phelan, and pressure mounted after the failure of the water supply during the 1906 Earthquake and fire. Eventually the Hetch Hetchy source was secured for the city, ending Spring Valley’s corrupt monopoly. |

The Spring Valley Water Company was a private company that held a monopoly on water rights in San Francisco from 1860 to 1930. Run by land barons, its 70-year history was fraught with corruption, land speculation, favoritism towards the moneyed elite, and widespread ill will from the general populace.

In 1850 San Francisco was a treeless windswept dunescape, receiving about 22 inches of rain a year, mostly in the winter. The few creeks running through the land could hardly support the instant city rising from the sand. It was clear that water would have to come from outside the city limits, and whoever controlled the water rights and delivery would control the city and its growth, and have unparalleled opportunities for development and great wealth.

George Ensign rose to the top in a competitive field shrouded in secrecy. The California Legislature had passed an act of eminent domain, permitting the taking of privately held land and water rights for the common good of cities. Thus empowered, George Ensign was able to seize rights of way to store and deliver water to San Francisco. In 1860 George Ensign incorporated the Spring Valley Water Works (later changed to Company), soon to become the state’s most powerful monopoly. For decades to come the power of eminent domain gave for the elite owning the water company an opportunity to acquire empires in real estate with land increasing in value as the water flowed in.

The California legislature had redrawn county lines in 1856, limiting SF County to the city limits, and giving the highest mountains, largest streams and expansive space to San Mateo County. Thus George Ensign had to look towards San Mateo for the water, and hired Col. Alexis Waldemar von Schmidt, a German military engineer, for the job. He redirected Pilarcitas Creek through tunnels and flumes, delivering the first water to San Francisco in 1862. Thus began an era of assured growth, land speculation, private fortunes and corruption.

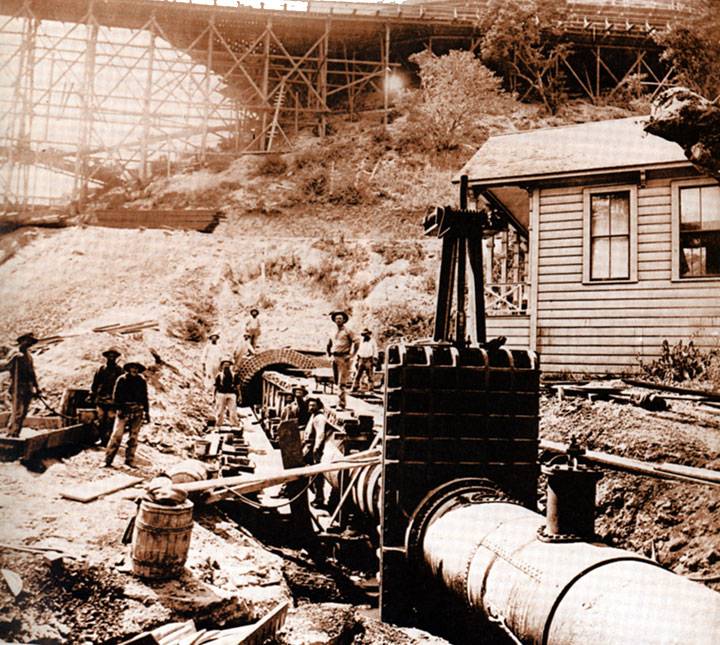

Pilarcitos Dam, winter 1866-67.

Photo: San Mateo County Historical Association

In 1865 Col. von Schmidt tried to break the monopoly of the Spring Valley Water Company by incorporating the Lake Tahoe and San Francisco Water Works Company to build an aqueduct from Lake Tahoe to foothill mines and San Francisco. It backfired, and Spring Valley Water Company acquired the failed company and firmly established its monopoly for the next seven decades.

Meanwhile Hermann Schussler, a Swiss engineer, was hired by Spring Valley to replace von Schmidt. He stayed with the Company for fifty years, while also consulting to leading capitalists and mining companies, an example of how deeply interconnected the water and land barons were.

Armed with the right of eminent domain and backed by San Francisco leading financiers, Schussler drove his conduits, flumes, and tunnel bores deeper into San Mateo County, tapping every major watershed along the Peninsula divide. He acquired 100,000 acres of prime watersheds and rights of way, raised real estate values, and benefited himself handsomely along with the San Francisco plutocracy.

Crystal Springs Dam, easterly outlet, c. 1860s.

Photo: San Mateo County Historical Association

Enter William Ralston. Ralston established the Bank of California in 1864, invited the most respected financiers and influential business magnates to join the board, and soon created one of the most powerful financial institutions in the West. Ralston had grandiose ideas for the Paris of the Pacific, including a “central park” to invite real estate development in the western sand dunes. He hired William Hammond Hall to carry out his vision of a proper green English-style park in the sandy Outside Lands. Under law, the City was obligated to provide the water, thereby destroying a beautiful natural environment outside the City to create an artificial “natural” environment in the Park. Hall was disturbed by the irony but seduced by power and money, and betraying his ideals he designed the 1,000-acre park.

Meanwhile, Schussler was barging ahead, building many large-scale water projects in the 1870s, including dams and hydraulic mines, all turning great profits for Spring Valley while leaving behind an expanse of human, animal and industrial waste. By bribing the City Supervisors, those who were supposed to supervise the Company, they could set their own rules and rates. When they announced they would no longer provide water for the growing needs of Golden Gate Park, the Supervisors attempted a corporate take-over to turn Spring Valley Water Company into a public utility.

As the Supervisors were planning the take-over, Schussler was exploring new sources of water for San Francisco’s continued growth, and decided on Alameda Creek whose watershed covered 700 square miles of tributaries through the Livermore Valley, and incidentally provided water for valuable farmland.

Before either the Supervisors or Schussler could take action on their plans, Ralston bought the Spring Valley Water Company along with the water rights to Alameda Creek.

Ralston’s immense fortunes rose and fell with his and the Bank’s pyramid schemes and wild speculation, and at this point Ralston was deeply in debt. So his plan was to sell certificates of indebtedness for Spring Valley stock at a higher price than they were worth, trade them for stocks to acquire control of Spring Valley, sell Spring Valley to the City, then sell his own interest in Alameda Creek water rights for a large profit. The scheme was stopped by public outcry, and the City Supervisors refused to buy the Spring Valley Water Company.

Then came “Black Friday,” August 26, 1875, when nervous depositors made a run on the Bank of California draining its assets and leaving Ralston $5 million in debt. The board of the Bank demanded that Ralston sign his personal assets over to William Sharon, his devious partner, and that afternoon during his daily swim, he either had a stroke or chose to take his life, leaving Sharon one of the wealthiest men in California. Sharon now owned the Palace Hotel, palatial estates, mills, mines, railroads, timberlands . . . and a controlling interest in the Spring Valley Water Company.

The 1890s saw a rash of development of communities down the Peninsula for the land barons who had made their fortunes in gold, silver, land speculation, railroads, and business ventures, shady and otherwise. Mansions with gardens modeled on British estates and Loire Valley chateaux required prodigious amounts of water, pushing the Spring Valley Water Company to proceed to expand into the Alameda Creek watershed.

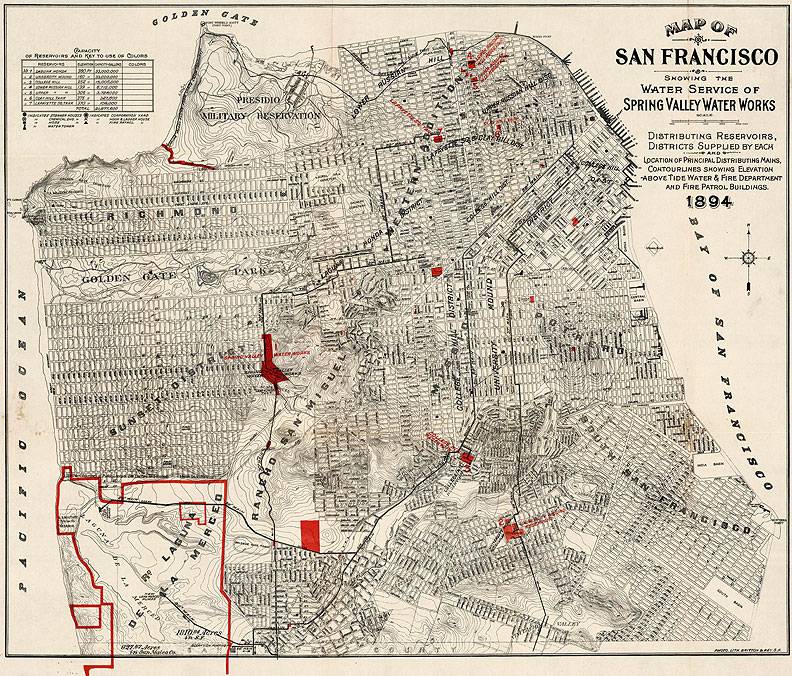

1894 Spring Valley Water Works facilities map.

Image: courtesy David Rumsey collection

By this time, the Spring Valley Water Company was largely owned and run by the wealthy elite of Hillsborough and nearby estates. Meanwhile there was a growing voice of discontent from San Francisco customers complaining of high rates and poor service, along with the farmers of Alameda County watching their wells and fields go dry.

The demand for water kept growing, this time from James Duval Phelan, an Irish immigrant, who had inherited an $11.5 million fortune along with substantial properties. A Progressive, he was elected Mayor of San Francisco in 1896 on the Reform ticket. His grandiose visions extended beyond the City to include a world-class metropolis. With water requirements far beyond the Water Company’s capabilities, he became fixated on the Tuolumne River and a Hetch Hetchy Valley reservoir (six years after Yosemite had been designated a National Park). To pay for this he advocated for public financing, public control of water systems, and government sponsored engineering projects.

Supporting Phelan’s grand ideas was William Hammond Hall, who upon completion of Golden Gate Park in 1878 had become State Engineer. He realized that the dams and aqueducts essential to the massive development of Phelan’s vision required staggering amounts of capital beyond private capabilities, and that only government treasuries could bear such costs. Further potential support came in 1902 from Congress’ passing the National Reclamation Act, thus creating a civilian army of engineers for large-scale projects. Phelan and Federal Agent Lippincott initiated the idea of claiming Hetch Hetchy as a reservoir within Yosemite National Park.

April 18, 1906, the San Francisco earthquake changed everything. As the city burned to the ground, fire hydrants delivered only a trickle of mud. Many blamed the Spring Valley Water Company for negligence. The disaster gave Phelan’s and Lippincott’s plan the urgency and support they needed. The City was fairly united in believing that they must have a reliable and steady source of water, and Phelan and Lippincott easily convinced them that only the Tuolumne would do that.

The building of Hetch Hetchy Dam took decades and is another story, but throughout this period the City tried to purchase the Spring Valley Water Company by putting bond measures on the ballot. Five times the measures failed as voters thought the price too high. Finally in 1930 the City purchased the Spring Valley Water Company for $41 million.

City Council of Half Moon Bay Meets ~ 1st and 3rd Tuesdays at 7:00pm

HMB City Council Agendas and Zoom Links

HMB City Calendar

The New Now ~ Virtual Remote Public Agency Meetings

- streamed live on Comcast Channel 27 and Pacific Coast TV website

- the City’s website online (via Granicus)

- and on Facebook Live

- one in English (City of Half Moon Bay FB Page)

- one in Spanish (City of Half Moon Bay Recreation FB Page)

- Recorded by Pacific Coast TV (PCTV)

Members or the public are welcome to submit comments (in accordance with the three-minute per speaker limit) via email

ing – (650) 477-4963 (English) and (650) 445-3090 (Spanish).

ing – (650) 477-4963 (English) and (650) 445-3090 (Spanish).

The City Council of Half Moon Bay

Half Moon Bay City Council Subcommittees

- CSFA Grant Selection

- Education

- Emergency Preparedness

- Finance

- Human Resources

- Legislative Affairs

- Mobility

Half Moon Bay City Council Strategic Plan