|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ESSAY. From Montaran Bill Softky.

In which the author, as a principled answer to the attitude called NIMBY (“Not In My Back Yard”), proposes that the United States federal government create a very specific kind of public park in the wilderness of Montara Mountain facing his house. This would be a “dark park,” which preserves the natural statistics of an ecosystem in addition to preserving individual creatures through technology. This high-bandwidth, multi-scale monitoring of Nature would be far more sensitive than methods now used by the National Park Service for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), and would help train visitors to keep the place dark and quiet. The author has not consulted his neighbors, nor fellow elected officials.

Why a Dark Park?

We Coastsiders, in general, love this place for its fog, forest, cliffs, and Natural beauty. We take our dogs, bikes, and knapsacks, and are lucky to live near others who do the same. This place is as close to Paradise as the urban Bay Area has access to, which is why so many outsiders come to our cliffs and trails for engagements, pictures of the sunset, and selfies.

The steep forbidding wilderness of Montara Mountain, facing my house of five years, is a kind of perfect wilderness. Horses sometimes amble across the flats, and the sharp lights of mountain bikes sometimes hurtle down horrific inclines. Except for a few power lines and radio towers, it’s pure Nature: a wrinkled, rounded wall of granite, coated in brush and swirled in fog. At the west, strings of pelicans thread their way upwind over the ocean; underneath are whales and great white sharks. The other alpha-predator, the mountain lion, lives in cloud-forest crevices way up. The rocky mountain ridge won’t hold trees; sometimes it’s lost in fog, sometimes it looks down on fog as from an airplane, sometimes the fog coats it like icing, or surrounds and cloaks everything. Montara Mountain hosts a host of microclimates, some damp, some dry, some sheltered, some exposed, all magical. So many places to be amazed, so much detail, so much hush.

Automatic cameras show the mountain lions, courtesy of the Puma Project. A mountain lion can lurk just feet from a trail without being seen. If people could be so graceful and quiet, hundreds could quietly listen to a guitar in the woods half a mile in front of my house, and I’d never know. Imagine: concerts in my front yard, and I want it to happen.

That’s what a Dark Park would do: it would coax and train people to blend into Nature, and as their reward they’d be saner and happier. Probably healthier too. The well-known ethos of “Leave no trace,” now extended beyond litter to artificial light and sound as well. Nature in her purest form, without weird lights and sounds and screens and interruptions, is scientifically proven to be good for us. And the less obtrusive we are, the more of us can fit in without disturbance.

The technology research done by my wife Criscillia and myself eight years ago proves, quite literally mathematically proves, that humans need Nature to recalibrate our mental models [Sensory Metrics of Neuromechanical Trust]. The peace and rejuvenation humans get from Natural spaces is real, measurable, and the perfect antidote to the world “over the hill” of deadlines, monetization, and screens. Those man-made mental tripwires with their thresholds and rules don’t match the continuous data format nervous systems expect. The filigreed fractals and sounds of Nature fit us perfectly.

Protecting Natural from Un-Natural Statistics

And now we can measure those filigreed fractals too, thanks to new technologies, and thus protect them better.

There are three technological components needed to monitor the health of ecosystems in real time. The obvious first two are hardware sensors and software processing, both now vastly cheaper than ever before. (I’ll get to those later). But very few people know the third piece, the one I happen to be an expert on: what to measure in the first place. The scientific phrase for this data-science subject matter is “natural statistics,” the quantitative measurement of Natural patterns in their native form and format. A subset of quantitative biophysics, my own latest scientific language.

The field was started in the 1990’s by my longtime neuroscience colleague Bruno Olshausen, now Professor and director of Berkeley’s Redwood Center for Theoretical Neuroscience. He and others like Dan Ruderman took pictures of Nature and looked for common textures. Lo and behold, fractals and fern-shapes and rivulets were everywhere. Patterns fast and slow, big and small, organic and inorganic, light and sound and chemical, anything which can be measured proves to have the same patterns at scales slow to fast, tiny to vast. Those different scales seamlessly knitted together provide a full-scale moving 3-D picture of the ecosystem, from the microsecond ultrasonic calls of hummingbirds and bats down to their annual population growth. Understanding all that data well enough to predict an ecosystem’s health must involve newly invented data technologies like multi-dimensional probability distributions (as in finance or astrophysics), distributed sensors, and real-time statistical algorithms. But now those will be aimed not at measuring human consumers but now at Nature as She is, in order to protect not exploit Her. If we measure what birds and wind sound like, we’ll then know how music and clanging differ from that. If we measure natural light, we’ll then know when too much blue messes up night vision and circadian rhythms for all us creatures. The core concept of the Dark Park is to use instrumentation and Big Data to protect the wholeness of Nature, for everyone’s benefit.

As relatable examples of natural statistics, let’s take blue light and traffic roar.

In all species, for sensible physics reasons, the eyes are extra-sensitive to blue light. Blue light is rare at night but is thereby really useful for synchronizing circadian rhythms. Plus, single blue photons are easier to detect, making blue crucial for night vision (airline pilots use red light to protect their blue-sensitive cells). In the natural world, we’re not supposed to see any blue at night at all, so mere exposure—through a screen, or LED lighting, or car headlights—can induce sleeplessness, anxiety, and headaches.

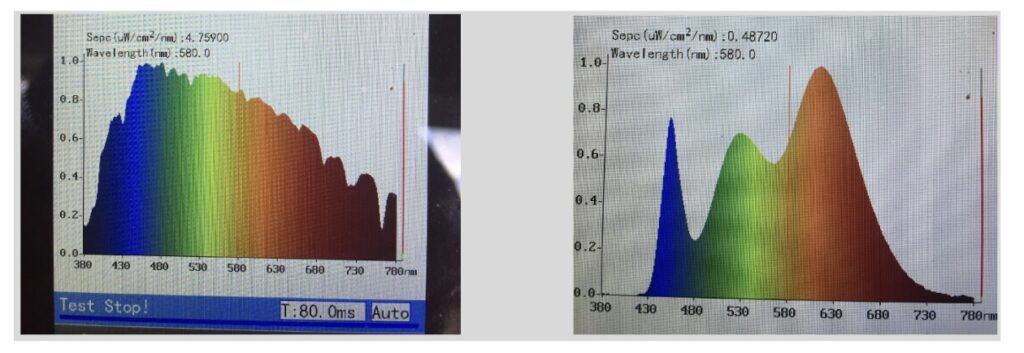

For years there has been a public-interest group protecting the dark skies which astronomers and wildlife need (the DarkSky Project). Locally, the Midcoast Community Council has discussed Dark Skies multiple times for school construction projects and had a scientific presentation by Dr. Travis Longcore. The Dark Sky project has for years documented all kinds of damage done by artificial light, damage to both people and Nature. Urban places, like “over the hill” in Silicon Valley, are doused with way too much blue light, from headlights and streetlights and security lights; that stress drives them here. But harmful LED lighting is cheap and minutely more energy-efficient than less harmful kinds, and industry has blocked medical science from investigating the harms in the first place. To show how simple these effects are to measure, I offer some pictures from my lab-bench at home.

On the left is a graph of natural sunlight, with very little blue. On the right is the spectrum from a LED headlamp. The shark’s-tooth blue spike on its left is the energetic source driving the other colors, but our eyes did not evolve for so much blue, and can’t adapt.

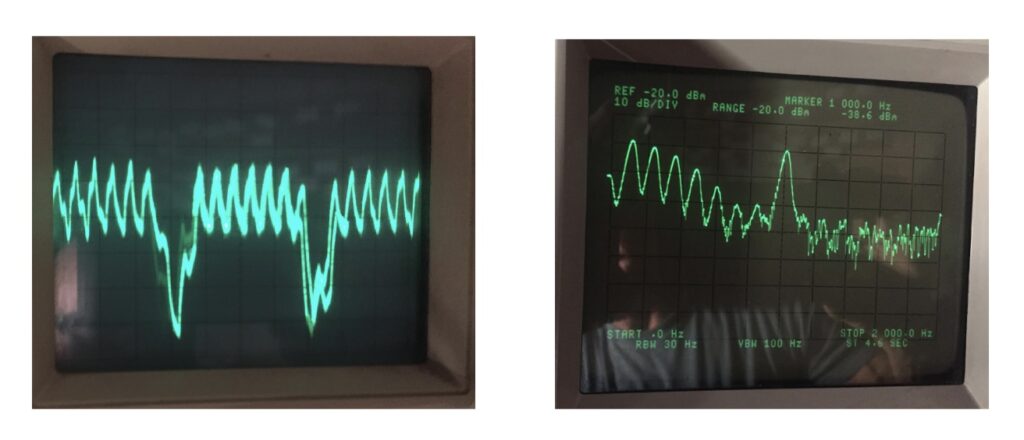

The problem isn’t just too much blue light, but too much flicker. Many people remember how fluorescent lights, introduced in the 1960’s, drove people to complain of headaches from flickering light. Now with LEDs the problem is much worse, because the flicker intensity went up from 20% to 100%, and the speed went up to hundreds of times per second, with microsecond switching.

Below are traces from two scientific instruments, an oscilloscope (blue at left) and a frequency analyzer (green at right), showing time the intensity fluctuation and power spectrum inflicted on our eyes by an undimmed LED can-light whose intensity was measured by a sensitive, fast detector. These traces together show the light is “screeching” in its ultra-fast on/off switching. (In fact, if this signal is connected to a speaker one can hear directly that the light sounds like a mosquito). Because such hyper-variable light sources never existed in Nature, our nervous systems cannot sense them directly, but we are deeply irritated and destabilized by them precisely because they are alien.

Likewise, the roar of artificial traffic (like I heard growing up in Menlo Park) is unnaturally steady and regular, and is bad for us; the irregular roar of surf and wind are the exact opposite, and good for us. In general, the organic sounds and ultrasounds of Nature have just the right texture to relieve human stress.

Building a Dark Park

Once a Dark Park is up and running, its automated attention will keep Nature looking and sounding Natural by tracking overall statistics for the scientists in headquarters. That firehose of data will make possible over-the-horizon hints long before anything actually goes wrong. But those same sensors will also, in the moment right there, whisper through hidden speakers encouragement to people who follow the rules regarding low-light and quiet, or growl disapproval at music or flashes which break the rules. Active, sensitive, neutral monitors will “gamify” the park experience to nudge park-goers into treating Nature with respect, thereby allowing more visitors to have better experiences while preserving Nature even better.

But how to get a Dark Park up and running, soon with not much money? The same way all technology develops, by starting with what you’re already good at, learning fast, and making the process fun. In my vision the Dark Park will be constructed by three formally adversarial but at core deeply collaborative teams: Team Sensor, Team Prowler, and Team Container.

Team Sensor tries to build a sensor which can “read” natural statistics so well, in real time, that it can detect and track deviations, such as outsiders.

Team Prowler on the other hand tries to sneak past those detectors, which means intimately learning their limitations. Team Sensor invents radar, Team Prowler invents under-the-radar evasion, both in tandem. Ideally, that makes a virtuous circle of technological improvement while managing that game gives Team Container their sea legs as referees.

With enough creative grad students and junior scientists, and a few tens of thousands of dollars in equipment, building the Dark Park might look like this.

Team Sensor would be my favorite to join, or just look in on. I’m a geek, a technologist, a tinkerer, a prototyper. I know how great research groups work (like those of Silicon Valley genius Carver Mead, and his many students). This team would be the first to read Nature in her native language, the language of ultrabandwidth vibrations, using the very latest sensor and algorithmic technologies, potent data-science tools honed over recent decades, so far only for corporations. To do multi-scale, multi-sensory, multi-spectral analysis of an ecosystem as it breathes and whispers to itself would be to know Nature’s heartbeat from the inside out, using the neutral, clean language of numbers.

Those vibrations have always been real, and now most are mostly detectable. Only now do we have the right sensors and sensor types, bandwidth and recording capacity, and general-purpose statistical algorithms with complementary superpowers that we can capture enough data to read if not yet predict how Nature evolves in real time. Until now, much discussion about vibrations in Nature has been called hippie talk, and gets it wrong by imagining electromagnetic vibrations rather than plain old mechanical ones like motion, sound and ultrasound. We know brains deal with exactly that. So now we can use battle-tested technologies of signal format, information flow, carrier waves, phase, 3-D orientation, latency, and resolution. In other words, now we have not only hardware and processing software but the crucial, quantifiable sensory metrics which encode organic trust and interaction.

Imagine being one of those scientists seeing and hearing this data the very first time. Imagine being the first to “hear” a flock of birds swerve and bank, just by listening to subtle signals embedded in their flaps and calls. Or to infer from sound and wing-flap frequency alone that pelicans reciprocally bounce off one another’s trailing vortices, as they co-evolve their upwind path like stringing beads on thread, one bird following another along a perfect curve through invisibly moving air. To sonically distinguish between species of birds, or insects, would force us to know how our own species does or doesn’t sound. (That knowledge of homo sapiens’ native vibrational capacities will be crucial for Team Container later on.)

I imagine Team Sensor hits the ground running by purchasing a bunch of cheap light-sensors ranging from the infrared to ultraviolet, and hacks up some amplifier circuits to measure intensity by the microsecond (an unusual innovation which lets them not only track overall color spectrum, like the extra blue from screens or infrared from fires, but also the momentary on/off way that natural sources like bugs, and tech sources like LEDs, modulate the light’s intensity).

After creating quick-and-dirty light analyzing gadgets, Team Sensor repeats those circuits with sound, using vibration-sensors to map Natures’ sounds and tremors into the techno-language of Fourier power spectra and multiscale 3-D wavefront synchrony. They then hook all those measurement gadgets up to tiny computerized data-loggers in waterproof boxes with batteries lasting a week, then plop them in nooks and crannies on Montara Mountain and its various cloud forests and swamps. They wait, and come back to harvest their data. Rinse and repeat.

Meanwhile Team Prowler gets a few of the sensors, so they can practice evading. Can they learn to walk on gravel without being heard? Do irregular footsteps, like the “sandwalk” in the movie Dune, make sensing difficult? Do camouflage clothing make it harder to be seen? Is a phone a dead giveaway? A word? A grunt? A hand-signal?

Back to Team Sensor. With their new data about how Nature works, and how their gadgets work, they can build live sensor proto-algorithms into deployable platforms interacting with live people. I imagine something like a streetlight in the forest or on the hillside, listening and looking for outliers, alternately coaxing and snarling. (I call it a SenTree in honor of using sensors to guard Nature, and looking like a tree). By the time SenTrees go live, Team Prowler already has trickery up their sleeves so they can “sneak up” on SenTrees and pinch their robotic butts. Both teams can see what works and doesn’t, aiming to do better next round.

Team Container learns crucial cues, such as what Sentrees can and cannot sense, and how their responses can be mis-interpreted by humans. The semi-adversarial approach in which Team Sensor and Team Prowler improve each other’s game is how the most potent algorithms, like AlphaGo, were able to evolve. After a few rounds both teams will be world experts on what Nature looks and sounds like, on which technologies can measure Nature in real time, and on how the human form can move in ways which look like Nature, and match our natural rhythms, and may or may not be detected.

All three disciplines get better at once: scientific understanding, measurement technology, and human behavior. A virtuous circle.

Building a Park out of Science

Turning scientific insight into a public park is where Team Container comes in. They have the hardest job, that of inventing a whole new way for people to interact with each other and Nature.

The concept of rules in parks is nothing new. Some places ban people altogether, some allow only hikers, some cars, some RVs, some snowmobiles. Rules about campfires and smoking and bathrooms and generators and multi-weeks stays. Rules for touching walls in caves.

In the Dark Park it’s not just the rules, but the spirit of the rules. I grew up backpacking, and have attended the desert festival Burning Man eight times now. In both situations there is a near-religious commitment to “leave no trace,” neither litter nor stain. As a general rule people like to collaborate and help (yes, even 12-year-old boys). If the team spirit of the park is not to bring gadgets and ruckus, the people who attend will self-select and naturally help others keep resolve.

Visitors to the Dark Park will be happy to be there. If they are told the nature of natural statistics, the subtle beauty of quiet, and are encouraged to blend in so that everyone can have the same hushed and reverent experience, as if in church, they will join in eagerly, help their friends, and enforce the rules as if their own. People want to help.

Furthermore, if they’re actually encouraged to sneak past the SenTrees, say by purchasing a manual in the giftshop written by Team Prowler, they will naturally cultivate an interlocking set of skills and sensitivities which can be honed and respected in near-infinite directions, and taught to others. Tracker-level skills. I bet some 12-year-old boys would enjoy learning physical spycraft. I would love to know, that the visitors lurking in the forests facing my house are silent mountain scouts, not loudmouth Homer Simpson.

Team Container will consult not only with designers of National Parks worldwide, but with designers of casinors, theme-parks, religious pilgrimages and ski resorts. How does our species naturally flock, how can we best be coaxed, what brings out our deepest primate collaborative instincts? How can technology teach us to be our best selves, and what are the best rules for making that happen? Their established practical knowledge will mix in with Team Sensor’s quickly filling dataset covering ecosystem vibrations to make a best-of-breed technical specification for what SenTrees should and could measure and do, and what park visitors should expect as rules and guidelines.

Will phones banned, or just light from them? Will red flashlights be issued at the gate? Will there be remote backpack-only campgrounds sworn to silence overnight? How many horses and mountain bikes, why or why not? Now they’ll finally have the numbers.

If Team Sensor, Team Prowler, and Team Container do their job, the Montara Dark Park will protect a local wonder of Nature while making it accessible to more people than a normal campground could.