|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

OWN VOICE. Thanks to Granada Community Services District (GCSD) Director, Matthew Clark, rebuts Gregg Dieguez’s conversation on his InPerspective blog.

This responds to Gregg Dieguez’ two articles recently published in Coastside Buzz, “The Iceberg of Public Works Deficits,” , June 7th, 2022, and “Public Works’ Capital Deficits – How Deep Is The Hole?” , June 16th, 2022.

I respond based on GCSD Board experience since 2003 and as a SAM Board alternate and regular Board member since then as well, so I can’t talk about the many other agencies and cities he’s included, not being knowledgeable enough. I do not speak for GCSD or our Board.

A physics student college friend announced one day “Who knew entropy was such a bitch?”* Having just read the famous African novel “Things Fall Apart,” I agreed. So, yes, your public works infrastructure is decaying; it’s always decaying, constantly, which is why agencies maintain reserves to timely fix the decay. Everything decays; entropy wins in the end. Nothing lasts forever and your public infrastructure needs to be maintained and improved constantly.

Fiscal analysis and some gauge for how and when to replace or renew assets are useful, in fact mandatory and in use at every agency, but just generating numbers only goes so far. However, responsible management, diligence, good practice, methods that have worked for centuries, and common sense (I know, as Will Rogers said, “Common sense ain’t common”) keep public works working, supplying the services needed at costs those serviced will support and can afford.

I appreciate Gregg’s work and analysis, he’s come up with interesting financial information about various local and relatively local agencies. Having tracked San Mateo County agencies’ finances over the years, primarily the ever escalating sewer service charges, I know the putting together of data Gregg has done is a lot of work; I can’t even reckon how much effort went into his analyses. But I think the large to huge “reserve deficiencies” defined by analysis for 16 of 18 agencies indicate it’s way off base on how things work in the real world.

The premises of both Coastside Buzz articles are explicit.

The first begins “Your public works infrastructure is decaying without a fiscally sustainable plan to replenish it.” This is at least debatable based on how public works infrastructure has functioned here for over a century; it may sometimes be complete balderdash but local situations differ greatly. Later in that first article comes: “… there is as yet no … metric to enforce the discipline of considering assets as PERPETUAL obligations of the public works entity, and the funding required to replenish those assets” (caps in original), which describes Gregg’s goal and the reason for the method proposed: to analyze the use life of agency assets compared to reserves to assess the adequacy of their specific financial situation. I don’t know how public agencies, or anyone else, are supposed to ensure assets and fiscal stability in perpetuity; that’s very much to ask and I think basically impossible because the future cannot be foretold.

The second article contains: “This analysis assumes that a utility should have reserves proportional to:

a) the current replacement costs of its assets, and

b) the age of those assets.” The implications of this premise as applied I can’t accept and try to explain why below.

The proposed analysis method and conclusions reached appear to address the question: what happens if X agency needs to replace ALL it’s assets? But that literally is never needed and never happens all at once. The “perpetual” obligations part doesn’t seem factored in, only the “should be able to replace everything” part is considered.

Start with the premises and assumptions quoted above, upon which the analysis and conclusions are based. Your public works infrastructure is decaying; agencies must maintain reserves to address that fact. Some agencies do much better at this than others and it’s not always the financially better off areas that do better, or worse. Responsibly run agencies have reserves to meet reasonably foreseeable needs and rates that replenish those reserves constantly.

Infrastructure needs for the next four or five or six years are often the basis for both the level of reserves maintained and the order in which those needs are met (hence 4-6 year Capital Improvement Projects [CIPs] appear to be most common). This doesn’t just pass for adequate and responsive fiscal sustainability, it functions well as such the great majority of the time. Responsibly run agencies have knowledgeable and attentive staff and governing bodies that notice and plan for when larger than usual CIP needs are impending and prioritize accordingly, which sometimes requires those detested rate hikes. The assumption that public works agencies simply don’t have fiscally doable plans to upgrade, repair, replace, and enlarge facilities as needed isn’t valid, but the key is “as needed.” If it was valid, infrastructure would always be in much worse shape than it typically is (this is not a claim it’s always as good as it ought to or could be, it never seems to be).

The first premise/assumption allows the jump to the second, phrased as “should have reserves proportional to…” a need to replace everything. This is opinion, not “fact;” who says such reserves should be required?

Gregg’s first premise and then second assumption appear to mean agencies should have reserves to cover replacement costs of ALL assets at ANY time, like tomorrow, instead of prioritized step by step. This reasoning carries through to the absurd: when an asset is replaced, the new asset goes right onto the list of assets the agency must be ready to replace again (they’re already decaying), so the agency should have not only the funds to replace assets they are currently replacing, but also simultaneously add whatever that cost was (plus inflation) to their reserves so they can be replaced again at any time, effectively more than doubling the cost of any asset replacement. Who does this? Should they? In addition reserves must increase every year to keep up with inflation of replacement costs, so right away agencies would be charging more than it actually costs to provide the services for which they are responsible, which isn’t legal in California.

Handling reserve needs simply isn’t done that way. That’s actually recognized by what Gregg calls “The Life Cycle Ratio, which is the percentage of reserves on hand compared to those required” to replace all assets minus most of what has just been replenished and somehow the total of percentage of remaining lifetime of all assets is calculated. How these figures are derived and their accuracy in each case I don’t know. Say an agency spends $1 million replacing an asset and assumes a 20 year useful life: does that mean that at asset-age one year reserves must be boosted $50,000 plus some guess at inflation or is the remaining 19 years somehow figured into the figure given for all assets? How useful or meaningful is a single figure for “Remaining Life” of all assets, the use life of which vary greatly? Example: GCSD/with SAM’s “Remaining Life” of assets is somehow figured to be 15.2 years; does this average the expected use life of HDPE pipe (makers claim at least 100 years) with computers and printers replaced every 4-5 years? How do partial replenishments and improvements figure in? How do expendable supplies figure in, are those assets? SAM has some basins (artificial concrete ponds) created in the 1970s or even earlier; they have been and are being updated, so what is the use life and how does that figure into the “Remaining Life” assessments presented?

The analysis treats asset depreciation as the same as the useful life of those assets, which it is not. Financial depreciation is an accounting issue that may partially address Gregg’s concerns, but has no real or simply calculable relation to the use life of an asset. Some assets remain in use well after fully depreciated, others may fail before fully depreciated or may become outmoded by additional demands, new technology, or regulatory changes. Suppose that new computer melts down in two years? What if plastic pipe makers are wrong, it actually lasts much longer, or only half the 100 years? (The American Concrete Pipe Association said in 2007 the Plastics Pipe Institute had recently claimed an astounding 2,893 years use life for some HDPE pipe, but says the PPI is wrong.) So, the precise figure of 15.2 years “remaining life” applies to what, precisely? Asset replacement cannot be planned on “averages.”

GCSD and SAM (Sewer Authority Mid-Coastside) have what are colloquially called “emergency reserves” but actually can also be used to cover asset replacements reasonably thought to be needed in the near future (expressed in ongoing CIPs), as long as the reserve is refilled. The State requires a reserve policy and that such reserves be “reviewed quarterly” (Civil Code §5550-5520) but does not require reserves be constantly sufficient to replace all agency assets at any time and only addresses “major components.”

Interestingly, the State does not seem to require reserves be funded, just that agencies have a reserve policy. Typically redundant sounding §5110(b) requires “The board shall not expend funds designated as reserve funds for any purpose other than the repair, restoration, replacement, or maintenance of, or litigation involving the repair, restoration, replacement, or maintenance of, major components that the association is obligated to repair, restore, replace, or maintain and for which the reserve fund was established.” I’m sure distinguishing between “assets” and “major components” has been and would be an interesting semantic exercise, probably largely settled by what is possible and affordable. CIV §5550(b) requires agencies be aware of and ready to identify such major components with a remaining useful life of less than 30 years, and plan how funding replacement of such components would be achieved, but does not require maintenance of that quantity of funds at all times, for good reasons.

Nevertheless, this analysis is founded in the idea, apparently, that public agencies “should have reserves” equal to the current (and future) cost of replacing everything at once, and compiles numbers that “…will represent aggregate averages for all capital assets” (except land). It uses the Army Corps of Engineers inflation calculations (the DOD is of course renowned for accuracy of cost estimations) rather than the Engineering Association or whatever agency engineers use, and calculations of estimated “Asset Lifetime,” which we know is fraught with just plain guesses and doesn’t factor in that vendors might over- or underestimate “useful life,” that some technologies must be abandoned before “useful life” is expended, or that some agencies have vital replacement parts at the ready that would also count as assets so you need reserves to replace the replacements. The analysis “calculate[s] the current replacement cost of the entire asset inventory” when nobody replaces the entire asset inventory all at once barring a total catastrophe that say, completely destroys the SAM plant and all its collection system too and every GCSD asset including all pipes in the ground–if that happens those numbers, very likely, will be rendered instantly meaningless because an entire new system with entirely new assets would be needed in the disaster aftermath.

The analysis also calls for agencies to constantly factor in inflation costs, so enough reserves today are not enough next week and need to be enlarged continually. The massive unfunded public agency pensions are only mentioned in passing (truly the wolf approaching the bank doors), I don’t think they factor into the calculations. Meeting the reserves agencies “should have” would require vast amounts of money endlessly needing augmentation.

Neither SAM nor GCSD has anything approaching enough reserves to replace all assets right now, or day after tomorrow, nor are they necessary.

It’s unrealistic to be ready to replace everything at once, ever–plus the State guidelines for existing reserves are much smaller than full replacement reserves and are “emergency reserves” for just that, emergencies when vital assets go bad or must be replaced immediately. The analysis emphasizes agencies should have 100% of reserves for total replacement of everything “WITHOUT BORROWING” (caps in original first article), which does impose huge additional final costs. So, it advocates that GCSD, SAM, etc., should have reserves able to fund replacement of everything it owns except land, like every foot of every sewer line and main, plus GCSD’s portion of all SAM assets. Seems rather unrealistic to me. Anybody want to calculate how high and how long we’d have to raise rates to accumulate such a stash of reserves? And how to explain to those paying for it that the reserved money will sit in accounts currently earning 0.5% or something like that. The only real yield of that huge reserve would be the security, I believe false, of purporting to be ready to replace every single asset at any time.

Also not factored in is that agencies can only charge the actual cost of providing services, not the cost of accumulating millions for reserves that are very unlikely to ever be needed all at once. “WITHOUT BORROWING” is emphasized, but the agencies would indeed be borrowing the money for huge potential future needs, only it’s from their customers, and holding the funds, getting nearly nothing in return (currently), and giving those who paid for it literally almost nothing in return.

And: insurance! Public agencies don’t have sequestered funds to replace everything, because they simply never replace everything at once but do what’s most needed next on a pay as you go basis, maintaining reserves for emergencies. Most people don’t have anything near the resources to replace their entire house and possessions should it be necessary, that’s why we have insurance. Public agencies also have insurance for unexpected covered costs (SAM is utilizing it right now). Why should agencies draw wealth from customers to that extent and hold it basically forever? They have insurance instead to cover at least some costs. (Is insurance a “asset”?)

“GCSD w/SAM” is shown as having $5.868 million dollars in reserve (I don’t know the source of this number; some must be allocated from SAM reserves. GCSD’s FY 21/22 Budget shows $4,294,661 in reserves including both sanitary and parks & rec functions). But according to the table presented and the “should have” concept, GCSD should have over $45 million in Reserve! That’s quite a deficit all right, were it true. The implication is that GCSD, about $45 million short for asset replacement funding, should extract at least another $40 million from our customers for sewer reserves.

Well, say GCSD has about 2500 residential and commercial sewer hookups (not exact but makes the math easier). It needs another $40 million soon. So each customer needs to cough up roughly $16,000 more for no new services nor expanded services and with asset replacement continuing at the current pace. As a Board Member, I would not like to try to convince our ratepayers we must add several zeros to their monthly service charges until we have over ten times the current reserves.

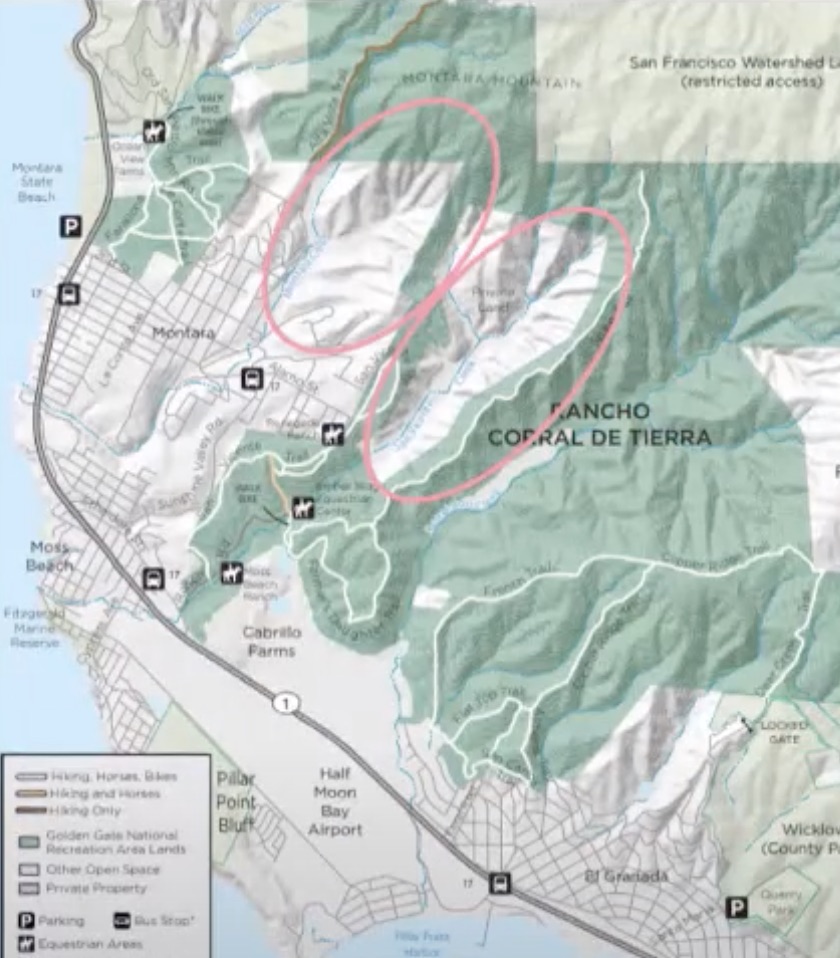

Gregg is in Montara so I assume within MWSD; the District is even further behind per capita (by the way, are all MWSD reserves counted in the ~$9.16 million, including the water side?), so do the math for that district–are ratepayers ready to be burdened with much higher rates until the reserves reach the “should have” level? And reserves must expand continually due to inflation. After rates skyrocket, pushing customers to actually examine MWSD budgets, how does the District answer the ratepayer who asks “What? You’re hiking already high rates to accumulate reserves meant to replace assets long after I’m dead? And I’m supposed to pay for it now? No way, let’s vote these idiots out!”

The analysis and results conflate “current replacement costs” with “eventually,” not the same thing at all. Eventually is also when those funds will be needed; much lesser reserves are needed to keep up with essential updates, paying as you go. If this reserves policy is really needed, why doesn’t any agency have the wisdom to enact it? I don’t know specifics about Belmont, but if I were in that district you bet I’d be demanding to know why the hell they have >$7 million more reserves than needed even under the “should have” requirement. The analysis shows Cal Water, a large supplier in San Mateo County, is deficient of “should have” reserves over $1.8 Billion! I think you would get the same response from that District and their ratepayers: when are we ever going to need to replace all assets? The answer: eventually, so that’s when we’ll need your money.

*I found out later this was far from an original thought or aphorism.