|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

VIDEO. From the May 4th, 2021 City of Half Moon Bay City Council meeting.

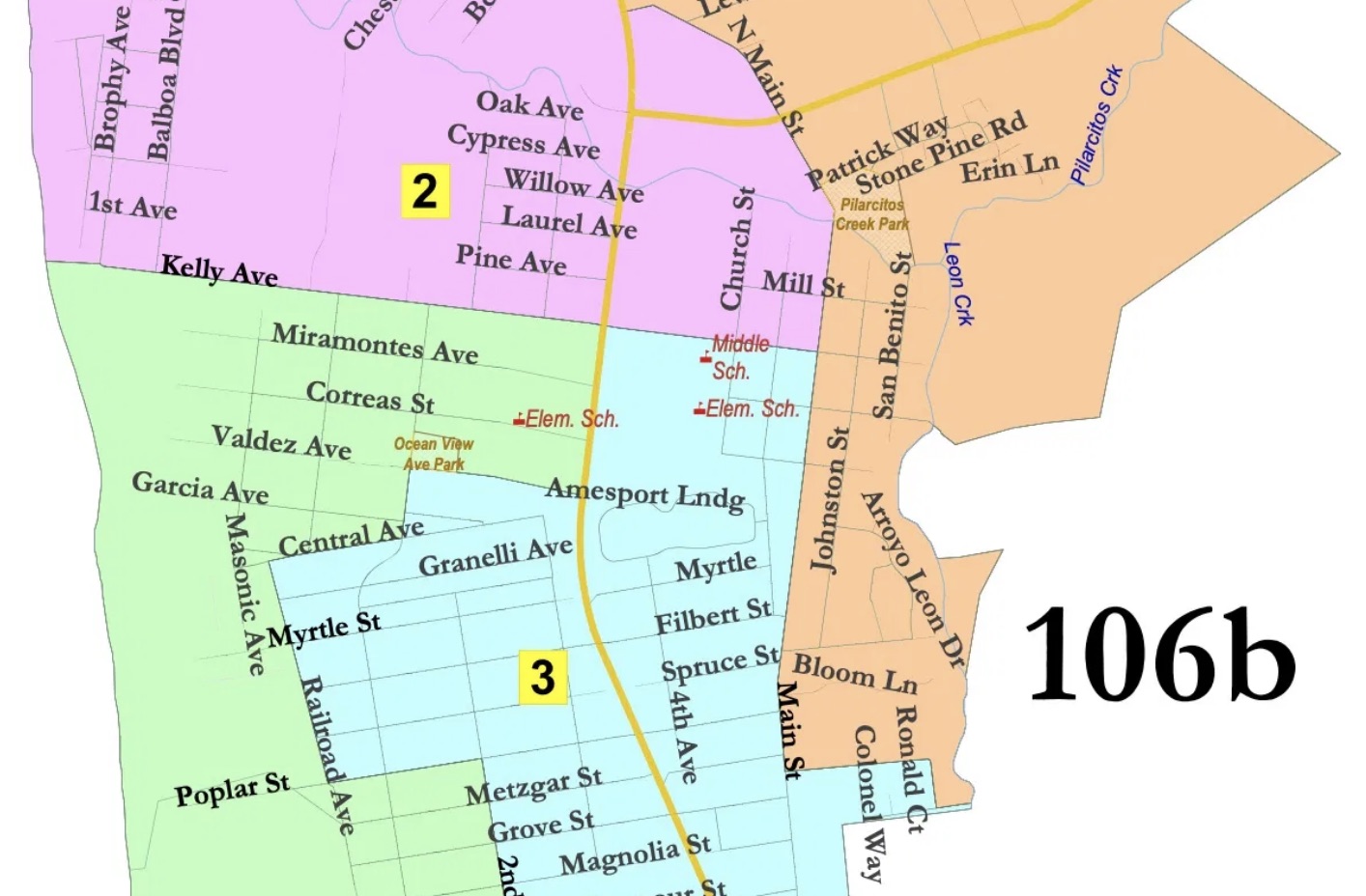

Applications Now Available for the 2021 City of HMB Redistricting Advisory Committee

PRESS RELEASE.

- Committee members must be residents of Half Moon Bay, and at least 18 years old.

- Half Moon Bay elected officials, their family members, staff members, or paid campaign staff are not eligible to serve on the Committee.

- The selection process will consider applicants associated with good government, civil rights, civic engagement, and community groups or organizations that are active in the City with the goal of forming a Committee with membership that is geographically diverse and consistent with the City’s emphasis on valuing diversity, equity, and inclusion.

From the American Enterprise Institute

A court challenge to California’s racial gerrymandering mandate

With the nation’s attention elsewhere, the U.S. Supreme Court was petitioned recently to take up Higginson v. Becerra, a case that challenges the constitutionality of the California Voting Rights Act.

If the justices accept the case and declare it unconstitutional, as they should, hundreds of California cities, school districts, and other jurisdictions that have been forced to adopt racially gerrymandered, single-member election districts during the last few years may choose to restore their previous nonracial forms of governance.

This is an important case, not only for Californians, but for the rest of the nation. In striking down the constitutionality of the CVRA, the court could restore the need for local California elected officials to build bridges between racial groups and represent the needs of their entire community, rather than a single racial or ethnic faction. It would represent an important victory in the endless battle against identity politics in California and throughout the country.

This case goes back to 2002, when California’s legislature, dissatisfied with a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that narrowed the use of race and ethnicity in creating election districts, passed the CVRA. The law essentially overturned the high court’s opinion, making it easier for racial and ethnic minorities to sue and demand racially gerrymandered voting districts.

Any city or school board that elected its members from at-large voting districts would now be at risk of being sued if minority candidates lost. All that was needed to prevail in a lawsuit was to show that minority candidates — usually Hispanics — weren’t being elected to office because of “racially polarized voting.”

So if white voters vote to elect a white candidate over a Hispanic one in an at-large election, then the system is rotten and must be changed. That is the crux of the CVRA. Unsurprisingly, the legislation had the support of left-leaning groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union, Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

But the U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation of when and how at-large voting systems are unfair to minorities is vastly different from what the CVRA now requires. In a 1986 redistricting case, justices created an empirically-driven, multi-part test to determine whether minority voters were being treated unfairly. While “racially polarized voting” is an element of the test, it is only one of the components a challenger must prove.

In contrast, the CVRA makes race or ethnicity the sole criteria in governmental decision making. This falls outside of what the U.S. Constitution allows.

Soon after the CVRA became law, a handful of aggressively clever California lawyers got busy recruiting plaintiffs to challenge the voting systems of dozens of jurisdictions. Initially, a few fought back, including the towns of Modesto and Palmdale. They lost and were forced to pay millions of dollars in legal fees and expenses. Since then, every jurisdiction even threatened with a lawsuit has immediately caved. By one estimate, about $20 million in legal fees to plaintiffs’ attorneys has been paid since the CVRA became law.

In 2017, the City of Poway (pop. 49,704) received a certified letter from attorney Kevin Shenkman asserting that Poway’s decades-old, at-large city council election system violates the CVRA. Shenkman wrote that “voting within Poway is racially polarized, resulting in minority vote dilution” and therefore must change, even though Poway’s Hispanic population is only 16% compared to 40% overall in California.

Based on the fees and expenses other jurisdictions had incurred in fighting Shenkman, Poway agreed to change its system. During the city council meeting to approve the settlement every member of the council voiced their objection to the changes the CVRA was forcing the city to make. One council member said that he was “proud of the job we do … but we have a gun to our heads, and we have no choice.”

Don Higginson, a former Poway councilman and mayor, was not going to watch this happen to the citizens he represented for over two decades. So, shortly after the council voted to adopt race-based districts, he sued California in federal court alleging the CVRA was a violation of the 14th Amendment. After a few years of legal wrangling, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against Higginson. He has appealed to the Supreme Court.

Much of this is going to be familiar to the justices on the high court, should they take the case. As Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote nearly 30 years ago, “Racial gerrymandering, even for remedial purposes, may balkanize us into competing racial factions; it threatens to carry us further from the goal of a political system in which race no longer matters — a goal that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments embody, and to which the Nation continues to aspire.”

O’Connor was right. And this law intentionally results in “divvying us up by race,” as Chief Justice John Roberts has previously put it. It drives racial-identity politics and leads to — indeed, requires — the creation of racially gerrymandered voting districts. All of this ultimately inhibits the creation of election districts and forms of governance in which the race and ethnicity of voters and their representatives become inconsequential.

The intent of the CVRA was to make race and ethnicity the only factors in how jurisdictions choose to govern themselves. Laws like this one will continue to fray the social fabric that holds us together as a nation. Let’s hope the justices take the case and strike it down.